Background

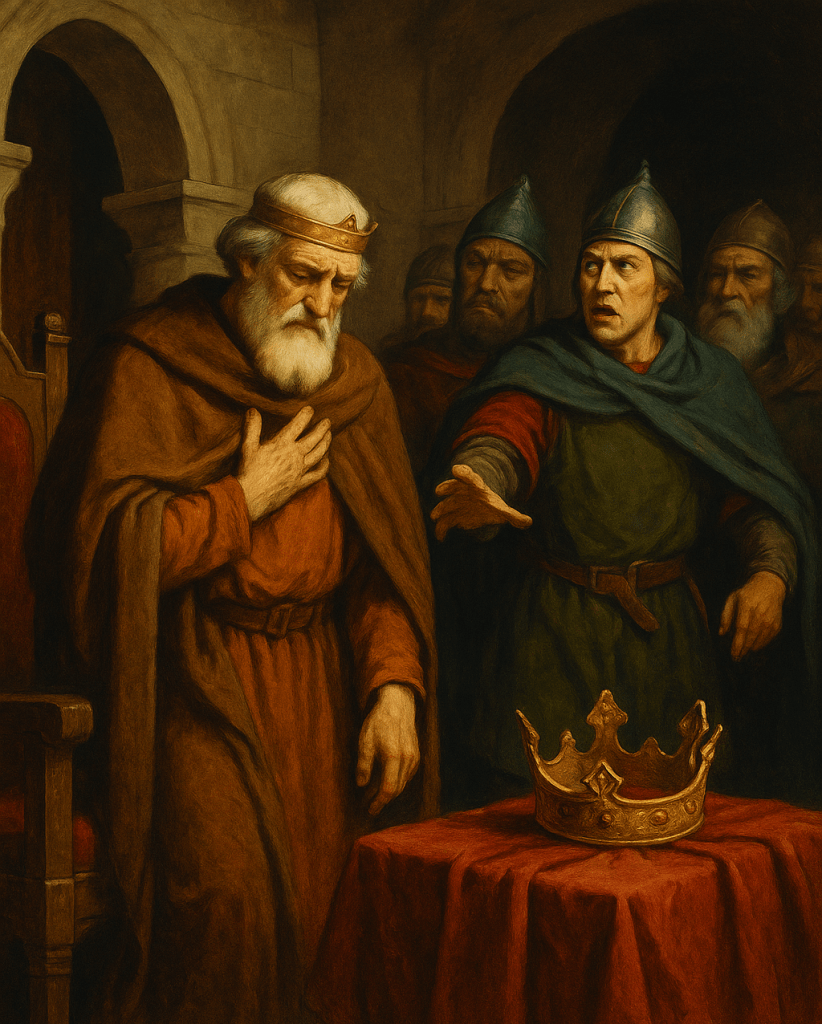

In 1146, Denmark was plunged into chaos and civil war following the unprecedented abdication of King Erik III Lam (r. 1137–1146). He was the first Danish monarch to voluntarily relinquish the throne, a decision that shattered what little political stability the realm possessed. With no legitimate heir to succeed him, the fragile balance of power between Denmark’s competing noble factions collapsed almost overnight, igniting a bloody struggle for supremacy.

Chroniclers writing in the aftermath of this turbulent period cast Erik in an unflattering light, branding him a weak and short-sighted ruler whose inability to secure a smooth succession plunged his kingdom into turmoil. Yet such harsh judgement may be unfair. Contemporary evidence suggests that Erik’s decision was not driven by political incompetence but by ill health. After stepping down, he retired to a monastery, where he died within a matter of months. The speed of his decline strongly implies that illness—not a lack of resolve—forced his hand.

Nevertheless, Erik’s abdication created a power vacuum that rival claimants were quick to exploit. With the throne unguarded, Denmark splintered into warring factions. Leading contenders, including Sweyn (Svend) III Grathe, Canute (Knud) V Magnussen, and the young Valdemar, each rallied their supporters among the nobility, plunging the realm into more than a decade of brutal feuding. What might have been remembered as a peaceful, devout end to a king’s reign instead became the spark that ignited one of Denmark’s bloodiest civil conflicts.

The Period of Three Kings

All three contenders were direct descendants of the Danish royal line, each backed by a faction of the kingdom’s elites in their bid to become sole ruler. Their support gave them legitimacy, and in separate ceremonies all three were crowned. To this day, despite ascending the throne in the same year and ruling concurrently, they are each recognised as Kings of Denmark. For nearly a decade, this uneasy arrangement of three rival monarchs endured, with shifting alliances and recurring wars as they vied for control of the realm.

But who where the three kings?

Sweyn III

Sweyn III (also called Sweyn Grathe, Danish: Svend III Grathe), born around 1125, was the illegitimate son of King Eric II of Denmark. After the murder of his father in 1137, Denmark fell into turmoil. The throne passed to Eric’s nephew, Eric III of Denmark, and Sweyn was pushed aside. During this time, he was raised under the care and influence of his powerful uncle, Asser Rig of Hvide, a member of the influential Hvide clan. The Hvide family’s support would later prove crucial in Sweyn’s bid for kingship.

When King Eric III abdicated in 1146, Denmark’s nobles failed to unite behind a single ruler. Sweyn was elected king by the nobles of Zealand and Scania, while Canute V, grandson of King Niels, was chosen in Jutland. This division plunged the realm into civil war, later complicated by the rise of a third contender: Valdemar, son of Knud Lavard. Valdemar initially supported Canute V but later shifted allegiances, creating a constantly shifting political landscape.

To strengthen his position, Sweyn allied with the German king Frederick I Barbarossa, recognising him as overlord in exchange for support. He was considered a capable but ruthless leader, quick to defend his claim and aggressive in battle. His reliance on the Hvide clan and foreign backers meant his rule was often seen as less “national” than that of his rivals. Nonetheless, he managed to assert authority over key regions, especially Zealand and Scania (Skåne), and was crowned king in 1154 with Frederick Barbarossa’s backing.

Canute V

Canute V (Knud V Magnussen), born around 1129–1130, was the son of Magnus the Strong and grandson of King Niels of Denmark. This made Canute part of the powerful House of Estridsen, giving him a direct royal claim. His grandfather Niels had ruled Denmark until 1134, when he was killed after a long civil conflict, and his father Magnus had also fallen in battle that same year. Canute was thus orphaned young but carried forward the dynastic claim of his line.

After the deaths of his father and grandfather, Canute’s early years were spent in a precarious situation. The throne passed to Eric II (Eric Emune), who had defeated Magnus. As a child claimant of a defeated line, Canute was sidelined, and it is believed he spent much of his youth away from the centre of power, possibly under the guardianship of loyalists in Jutland or abroad. His youth in relative obscurity shaped him into a cautious but ambitious man, aware of the fragile balance of power among Danish nobles.

After Eric III’s abdication in 1146, the nobles of Jutland elected Canute as king, recognising his descent from King Niels and the Magnus line. Meanwhile Sweyn held Zealand and Scania. For years, neither could gain supremacy, and their rivalry kept Denmark fractured.

Canute initially gained an advantage when Valdemar, son of Knud Lavard, joined his cause. The two young men grew close and even pledged brotherhood-in-arms, a personal and political alliance common in Scandinavian noble culture. With Valdemar’s support, Canute was able to temporarily strengthen his position and counter Sweyn’s advances.

Unlike Sweyn, who looked south to the Holy Roman Empire, Canute’s strength lay in traditional Danish noble support. He sought papal recognition to strengthen his legitimacy and portrayed himself as the rightful, “native” king against Sweyn’s German-backed claims. However, his limited resources meant he was often on the defensive and reliant on shifting alliances.

Canute was remembered as courageous and principled, but less ruthless and politically cunning than Sweyn. Chroniclers describe him as more idealistic, willing to trust his allies—especially Valdemar. This trusting nature would later contribute to his downfall, but before the Roskilde episode, it made him a rallying figure for nobles wary of Sweyn’s foreign connections.

Valdemar

Valdemar was born in 1131, only days before the murder of his father Knud Lavard, Duke of Schleswig. Knud was a popular and powerful Danish prince, and his murder by Magnus the Strong (father of Canute V) sparked a civil war that dominated Danish politics for decades. Valdemar’s mother was Ingeborg of Kiev, a Rus’ princess, which gave him important ties to Eastern Europe through the powerful Rurikid dynasty.

Because his father was slain while he was still an infant, Valdemar grew up in the shadow of blood-feuds and dynastic strife. He was placed under the guardianship of Danish nobles who supported his father’s cause, and from an early age, he was recognised as a potential claimant to the throne. His very existence embodied both a threat and a hope: a threat to those who had supported Magnus’s line, and a hope to those who had loved Knud Lavard and opposed the murder. His mixed Danish and Rus’ heritage added prestige, but it also meant he had to survive in an environment where rival branches of his own family dynasty fought for supremacy.

By 1146, as Sweyn and Canute divided the kingdom, Valdemar emerged as a third claimant. His father had been beloved by many nobles and peasants, which gave Valdemar a powerful symbolic legitimacy, even if he lacked immediate power in his teens. Still young, he first aligned with Canute, their families bound by shared enmity towards Magnus’s line. Fighting alongside Canute, Valdemar gained recognition as a charismatic and pragmatic leader, able to command loyalty across factions.

Unlike Canute’s idealism, Valdemar was strategic, willing to adjust alliances when needed. By the early 1150s, he had established his own power base in Jutland, no longer just Canute’s ally but an independent force. This ability to balance loyalty with ambition would set the stage for his eventual rise as a king in his own right in 1154.

Blood Feast of Roskilde on 9 August 1157

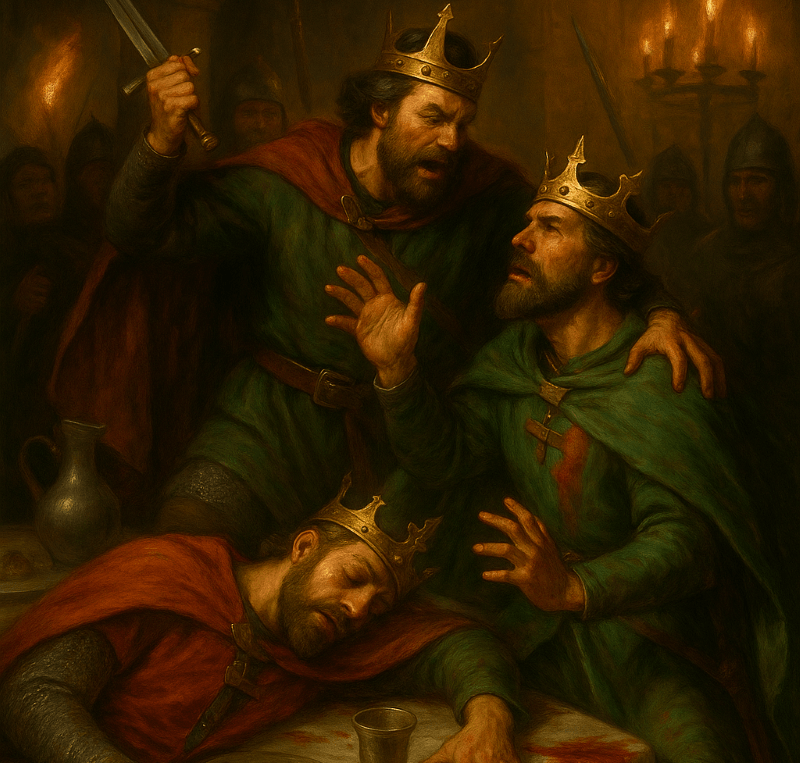

On 9 August 1157, the great hall at Roskilde was filled with light, noise, and the scent of roasted meats. After years of shifting alliances and open war, the three kings of Denmark — Sweyn III, Canute V, and Valdemar — had agreed to a settlement: the realm would be divided three ways, and peace would be sealed with a ceremonial banquet.

The feast was lavish. Long tables groaned with food, and wine and mead flowed freely. Nobles from across Denmark were present, eager to witness what they believed might be the end of a generation of strife. Sweyn played the gracious host, greeting his rivals warmly and raising cups in friendship. Toasts were made, and for a time the gathering had the air of reconciliation.

Yet beneath the display of unity, betrayal was being prepared. Sweyn had laid a deadly plan, stationing his armed men nearby. As the feast reached its height — when voices were loudest, cups fullest, and guards least wary — the signal was given.

The hall turned into a battlefield. Sweyn’s soldiers burst in, weapons drawn, striking down Canute and his companions. Canute himself was killed in the melee, cut down before he could escape. Valdemar, though wounded in the leg and arm, fought his way through the attackers, seizing a horse and fleeing into the night. Those who survived recalled the horror of the moment: the clash of steel among overturned tables, the screams of dying men drowning out the laughter and music that had filled the hall only moments before.

Sweyn believed the deed had secured him Denmark once and for all. But the treachery had the opposite effect. The nobles who had tolerated years of division turned against him, horrified by the violation of hospitality and kinship. Valdemar, though badly injured, reached Jutland, where news of Canute’s murder roused outrage.

Only weeks later, the two surviving claimants met in open battle at Grathe Heath. There, Valdemar’s forces shattered Sweyn’s army. Sweyn was killed as he fled, his corpse left in the marshes. From that moment, Valdemar I ruled alone.

The Blood Feast of Roskilde was meant to end the rivalry in Sweyn’s favour, but instead it became the final act of Denmark’s long civil war. The betrayal at the feast ensured Sweyn’s destruction and paved the way for Valdemar’s reign as sole king. His reign, remembered as the beginning of a stronger, more unified kingdom, would later earn him the title Valdemar the Great.

Leave a comment