The Early Life: A Young Pope in a Corrupt Age

In the early 11th century, Rome was dominated not by spiritual authority but by powerful noble families who treated the papacy as a political prize. It was in this climate of dynastic ambition and ecclesiastical decay that Theophylactus of Tusculum, the future Pope Benedict IX, was born around 1012.

As a member of the influential Tusculani family, Theophylactus was heir to immense wealth, private armies, and vast estates in Latium. His father, Count Alberic III of Tusculum, had already succeeded in placing two sons—Benedict VIII and John XIX—on the papal throne, effectively turning the Eternal City into a hereditary stronghold for the family’s ambitions.

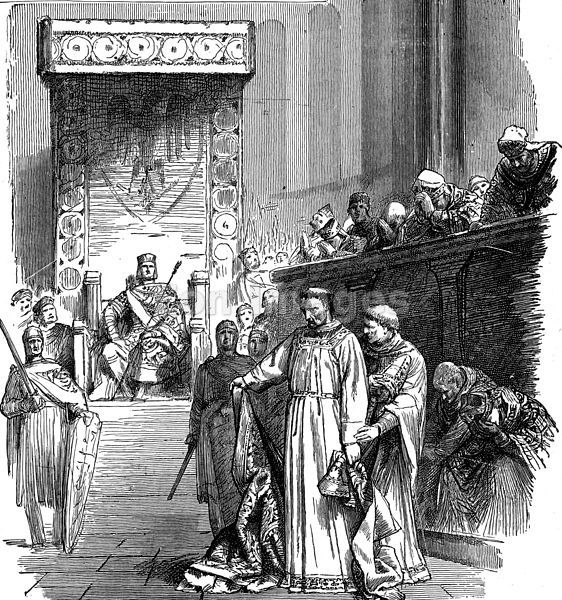

From adolescence, Theophylactus was groomed for power, moving through the lower clerical ranks in preparation for higher office. When his uncle, Pope John XIX, died in 1032, the Tusculani swiftly manoeuvred to install him as pope, allegedly securing his election through bribery and political influence. At the time, he was likely no older than 18 or 19, making him one of the youngest popes in history. Some sources even claim he was as young as 11 or 12, based on an unverified account by the monk Rodulfus Glaber, though most historians consider this unlikely.

Understanding Benedict IX’s early life requires a deeper look at the socio-political landscape of 11th-century Rome. Rome itself was in turmoil. The Church had long been plagued by nepotism, simony, and factional violence, with the Crescentii and Tusculani families, two dominant clans, vying for control of the papal throne. The Lateran Palace functioned more as a princely court than a religious centre, and spiritual authority had been undermined by decades of political interference.

This so-called “Saeculum obscurum” or “dark age” of the papacy allowed men like Theophylactus to rise to power as much through family connections as through faith. Even as a child, Theophylactus would have witnessed first hand how Church offices were bought and sold, how bishops answered to noble houses rather than to God, and how Rome’s sacred spaces could become battlegrounds for familial feuds.

This backdrop shaped his character in ways that would later scandalise both contemporaries and posterity. Chroniclers later depicted Benedict IX as corrupt, violent, and unfit for office. Pope Victor III claimed that his predecessor “committed so many vile adulteries and murders that his life was like a wild boar in the forest.” While these accounts may be coloured by later reformist agendas, they reflect a wider perception of a papacy mired in moral failure. Yet Benedict IX was not the cause of this decay but a product of it—a symptom of a system where Church offices were bought, sold, and inherited like noble titles.

His youth, privilege, and the corrupt environment that shaped him would later fuel some of the most infamous episodes in papal history, including the unprecedented sale of the papacy itself. Benedict IX’s early life thus reflects an era where power eclipsed piety and the boundaries between sacred office and secular ambition all but vanished.

The First Pontificate (1032–1044): A Reign of Scandal and Tumult

Benedict IX’s first pontificate lasted roughly twelve years, marked by controversy from the outset. It would become one of the most scandal-ridden and destabilising episodes in the history of the medieval Church. His father, Count Alberic III of Tusculum, the most powerful nobleman in Rome at the time, orchestrated his election, making him the third pope in a dynastic line that reduced the papacy to a family inheritance.

Contemporary sources and later chroniclers condemned the election as tainted by simony, alleging that Alberic III paid off influential clergy and Roman nobility to secure the position for his son. Even before Benedict had taken up the mantle of Peter, discontent stirred among those who saw the office of the pope reduced to a tool of secular power.

Benedict IX’s personal conduct during his first pontificate was the subject of intense and enduring controversy. Chroniclers painted a damning portrait of Benedict’s character, describing a pope more interested in worldly pleasures and power struggles than spiritual leadership. Pope Victor III later wrote of his “rapes, murders and unspeakable acts of violence and sodomy. His life as a pope was so vile, so foul, so execrable, that I shudder to think of it,” while others spoke of debauchery and disregard for religious observance. Although such reports may be exaggerated, they underscore the widespread discontent his rule inspired.

Rome at the time was a violent and unstable city, often torn by street fights between rival factions of the noble families like the Crescentii plotting against Tusculani dominance. The pope, as a secular prince as well as spiritual leader, was expected to manage both the spiritual needs of Christendom and the physical control of the Eternal City. But Benedict IX seemed more interested in earthly pleasures and power games than in guiding the faithful.

Benedict IX’s position was secure for the first years, backed by his family’s influence and imperial support, but unrest simmered. Rumours abounded of immoral escapades, public scandals, and a lack of concern for religious observance. Whether these claims were exaggerated or not, they contributed to mounting discontent among the Roman clergy and laity alike. The Roman populace grew increasingly resentful of Benedict’s excesses and the Crescentii family also sought to break the Tusculani dominance. In 1036, he was briefly forced out of Rome, only to return with aid from Emperor Conrad II.

By 1044, opposition to his rule boiled over. A popular revolt, likely encouraged by both anti-simony reformers and Tusculani rivals, forced him to flee once more. In his absence, John of Sabina was elected as antipope Sylvester III, delivering the first major blow to Benedict’s papal authority and marked the beginning of a dramatic unravelling.

The Second Pontificate (April–May 1045): A Brief Return and Scandal

In April 1045, Benedict IX regrouped with the support of his family, the Counts of Tusculum, marched back to Rome, gathered armed supporters, and forcibly reclaimed the Lateran Palace, effectively deposing Sylvester III and reasserting himself as pope.

This reinstallation marked the beginning of his second pontificate, though even at this stage, his position remained unstable. Rome was bitterly divided, and Benedict’s return did not calm the waters. Rather, it further inflamed tensions, both among the clergy and the lay population, many of whom were appalled at his earlier conduct and deeply suspicious of his motives.

His return was viewed by many as a power grab—not a move guided by spiritual duty, but by ambition and family interest. Some chroniclers suggest that he desired the papal office only to legitimise a marriage or advance personal wealth, rather than for any ecclesiastical purpose.

Rumours quickly spread that he sought to marry—perhaps even a close relative—and recognised that this was incompatible with holding the papacy. Faced with ongoing political resistance, deteriorating support, and a growing crisis of legitimacy, Benedict appears to have negotiated a transaction that would leave an indelible stain on Church history.

In May 1045, Benedict IX formally resigned the papacy and sold the office to his godfather, John Gratian, a respected archpriest known for his piety and integrity. The payment reportedly amounted to a significant sum, though exact figures are lost to history. Gratian, who took the name Pope Gregory VI, was regarded by many as a likely reformer, and his accession was widely welcomed.

This event was unprecedented: never before had the papacy been bought and sold so blatantly. Even though simony (the buying and selling of Church offices) was sadly common during this period, the public nature of this transaction and its association with the highest religious office in Christendom provoked outrage and disbelief.

The act set off alarm bells not just in Rome but across Christendom. Reformers who had long been warning of moral decay at the heart of the Church now had undeniable evidence that the office of the pope itself could be treated as a commodity.

Benedict IX’s second pontificate, lasting barely a month, is widely regarded as one of the darkest chapters in papal history, leaving consequences that reverberated far beyond its brief duration. While he had technically resigned, the legality and morality of the sale were questioned almost immediately. Reformers, particularly those aligned with the later Gregorian Reform movement, saw the incident as proof of the need for sweeping changes in how the Church was governed.

The Third Pontificate (1047–1048): The Final Grasp for Power

Benedict IX soon regretted his resignation and returned to Rome, taking the city and governing it, although Gregory VI continued to be recognised as the true pope. At the time, Sylvester III also reasserted his claim.

Although Gregory was considered a man of integrity, the purchase of the papal office was seen as an act of simony, leaving his position vulnerable. In December 1046, King Henry III of Germany (soon to be Holy Roman Emperor) intervened to end the chaos. At the Synod of Sutri, three claimants were removed: Gregory VI for simony, Sylvester III as an antipope, and Benedict IX, who was formally stripped of legitimacy in absentia. Henry III then appointed Suidger of Bamberg as Pope Clement II, ushering in a reformist agenda.

When Clement II died suddenly in October 1047, a power vacuum emerged. Benedict IX, supported by his influential Tusculum family and loyal Roman factions, seized the opportunity and forcibly reclaimed the papacy. However, his third reign lacked both widespread support and imperial recognition. Reformers in Germany and northern Italy, backed by Henry III, viewed his return as a direct threat to the integrity of the Church. In July 1048, the emperor appointed Poppo of Brixen as Pope Damasus II, who, with military backing, drove Benedict IX out of Rome for the last time.

After His Final Expulsion (1048)

Following his third and final removal, Benedict IX retreated to the Tusculani estates near Rome, vanishing from political life. Some sources suggest he was later excommunicated for his uncanonical return and earlier acts of simony. Other reports claim he repented, possibly spending his final years in penance at a nearby monastery such as Grottaferrata.

He likely died around 1056 in the Tusculum region, with later accounts placing his burial at the Abbey of Grottaferrata, though this remains uncertain. Benedict IX’s legacy was one of controversy: three papacies, a sale of the papal office, and a series of exiles that deeply undermined the moral authority of the Church. Yet his scandalous career helped spark the Gregorian Reform movement, which sought to end simony, enforce clerical celibacy, and free the papacy from aristocratic and secular control.

Benedict IX’s story concluded in quiet exile, stripped of power and reputation. While his reigns left the papacy tarnished, they also set the stage for its eventual transformation, making him one of the most infamous—and consequential—figures in medieval Church history.

Leave a comment