In early December 1872, the American merchant ship Mary Celeste was found adrift in the Atlantic Ocean, roughly 400 miles (650 km) east of the Azores, by the British brig Dei Gratia. The vessel was in seaworthy condition, with her sails partially set and her cargo of industrial alcohol largely untouched. Below deck, there were no signs of violence or struggle—food supplies remained plentiful, the crew’s personal belongings were undisturbed, and the ship’s log gave no indication of any looming threat. Yet, the entire crew, along with Captain Benjamin Briggs, his wife Sarah, and their two-year-old daughter Sophia, had vanished without trace. The ship’s lifeboat was missing, but no distress signal had ever been sent. The Mary Celeste thus entered history as one of the sea’s most perplexing mysteries—a ghost ship adrift on open waters, its unanswered questions fuelling speculation and intrigue for generations.

Origins of the Mary Celeste

The vessel that would become known as the Mary Celeste was originally launched under a different name. Built at the Joshua Dewis shipyard in Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia, in 1861, she was christened Amazon. Designed as a brigantine, the ship measured just over 100 feet in length and was intended for cargo transport across the Atlantic. Initially Canadian-owned, the Amazon had a troubled early career, including the sudden death of her first captain on her maiden voyage and a collision with another vessel in the English Channel.

In 1868, after several changes in ownership and a series of unfortunate incidents, the ship was sold to a group of American investors and registered in New York. It was during this transition that she was renamed Mary Celeste. Under her new name and with an American registration, she underwent significant repairs and refitting, including raising her hull and increasing her tonnage, making her sturdier and more suitable for long voyages.

By the early 1870s, the Mary Celeste was a solid, well-maintained merchant ship under the command of experienced seafarers. The events that followed would forever overshadow her origins, turning an ordinary cargo vessel into the subject of one of history’s greatest nautical enigmas.

The Crew on the Last Voyage

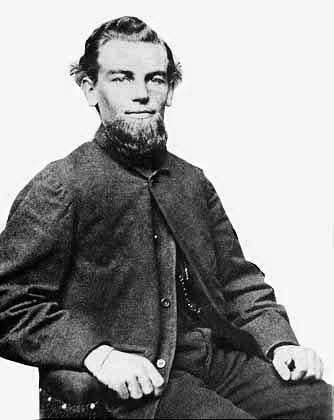

When the Mary Celeste set sail from New York Harbour on 7th November 1872, she was under the command of Captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs, a highly respected and deeply religious mariner with over a decade of experience at sea. Born in Massachusetts in 1835, Briggs was considered a man of strong character and sound judgement. He held shares in the ship and had a personal investment in the voyage’s success.

Accompanying Captain Briggs on this journey were his wife, Sarah Elizabeth, and their two-year-old daughter, Sophia Matilda. Briggs had decided to bring his family along, as he believed the voyage to be relatively safe and routine. Their presence on board adds a poignant human dimension to the tragedy that would unfold.

The rest of the crew consisted of seven hand-picked men, all considered capable and reliable. Among them was First Mate Albert G. Richardson, a seasoned sailor and fellow New Englander whom Briggs trusted implicitly. The Second Mate was Andrew Gilling, a young but competent officer of Danish descent. The steward, Edward William Head, was an Englishman responsible for provisions and the galley. The remaining crew were able-bodied seamen: brothers Volkert and Arian Martens, both of German origin, and two others—Bosanquet and Anderson—believed to be similarly experienced.

With a total of ten people aboard, including the Briggs family, the Mary Celeste left port fully manned, stocked, and in good order. Nothing in their background, behaviour, or the ship’s condition prior to departure gave any indication of the mystery and tragedy that would soon envelop them all.

The Purpose of the Fateful Voyage

The Mary Celeste set sail from New York on 7th November 1872, bound for Genoa, Italy. Her cargo consisted of around 1,700 barrels of industrial alcohol—specifically methanol—destined for commercial use in Europe. The voyage was a typical transatlantic crossing for a merchant vessel of the time, and there was no indication that it would be anything but routine. Captain Briggs, a meticulous planner, ensured that the ship was fully provisioned with food, fresh water, and supplies intended to last six months. The weather was reported to be fair at departure, and the vessel was considered seaworthy, especially after recent maintenance and refitting.

The Finding of the Ship

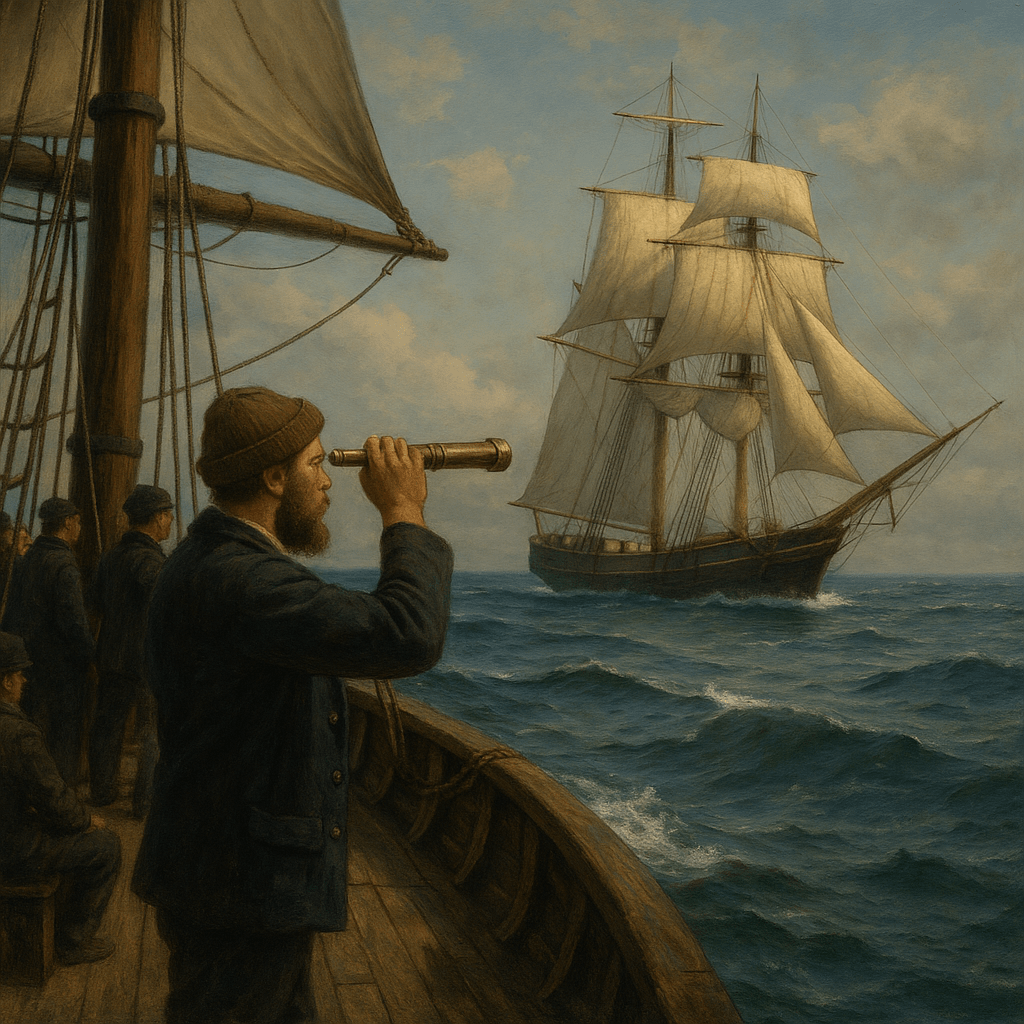

On 5th December 1872, nearly a month after her departure, the Mary Celeste was spotted by the British brig Dei Gratia, approximately 400 miles east of the Azores. The Dei Gratia‘s captain, David Morehouse—who reportedly knew Captain Briggs—was puzzled by the erratic movement of the ship. The sails appeared awkwardly set, and the vessel did not respond to signals.

A boarding party led by First Mate Oliver Deveau was sent across. Upon boarding, the crew of the Dei Gratia discovered a chilling scene: the Mary Celeste was completely deserted. There were no signs of life, no distress signals, and no immediate explanation for the crew’s disappearance.

The State of the Ship

The Mary Celeste was found in a seaworthy condition. Her hull was intact, and although she had taken on a small amount of water—just over a metre deep in the hold—this was not uncommon for a vessel of her type and age. The sails were set but in poor shape; some were torn, and others were missing altogether. Her rigging was slightly damaged, but again, nothing that would normally warrant abandonment.

The ship’s lifeboat, however, was missing, suggesting it had been launched intentionally. Inside, the galley was well-stocked with food and cooking utensils, and the crew’s personal belongings, including clothes and valuables, had not been taken. The ship’s logbook was found in the mate’s cabin, with the last entry dated 25th November, nine days before the vessel was discovered. The entry placed the ship near Santa Maria Island in the Azores.

Curiously, some items seemed out of place. The ship’s only pump was found dismantled, and one of the ship’s binnacles—used for housing a compass—was damaged. Navigation instruments and the ship’s papers, except for the log, were missing. These anomalies only deepened the mystery, offering no clear indication of panic or disaster.

Salvage Hearings

Despite being adrift for over a week, the Mary Celeste had not suffered severe weather damage, and her cargo of alcohol was largely untouched, save for nine barrels later found empty—believed to be made of red oak and thus more porous than the rest. With no bodies, no signs of struggle, and no definitive evidence of mutiny, piracy, or foul play, the fate of the Mary Celeste‘s crew has remained one of the most enduring mysteries in maritime history.

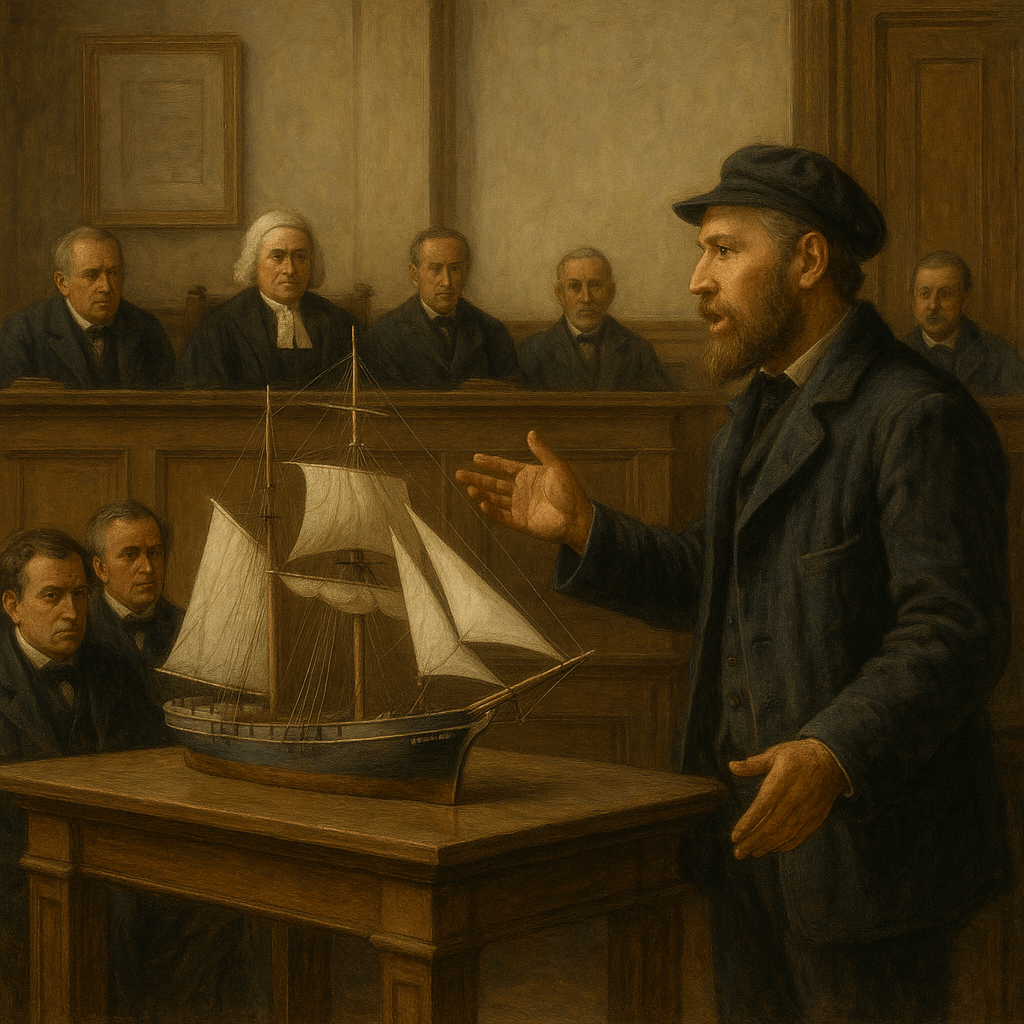

Following the discovery of the abandoned Mary Celeste, Captain David Morehouse of the Dei Gratia made the decision to bring the ship to Gibraltar to claim salvage rights—a standard maritime practice when a vessel is found derelict at sea. The Mary Celeste arrived in Gibraltar on 13th December 1872, where she was immediately placed under the jurisdiction of the Vice-Admiralty Court.

The salvage hearing was overseen by Frederick Solly-Flood, the Attorney General of Gibraltar, who approached the case with great suspicion. From the outset, Solly-Flood was convinced that foul play had taken place. He questioned why such an able crew would abandon a sound ship, and he began to suspect that the Dei Gratia crew might have had a hand in the mystery, possibly to profit from salvage.

An exhaustive investigation ensued. The ship was inspected in detail, and the testimony of both crews was heard. Solly-Flood focused heavily on small anomalies: a sword found with rust stains (initially thought to be blood), some scratches and marks on the deck, and the missing lifeboat. He also pointed to the disassembled bilge pump and torn sails as signs of possible struggle or sabotage.

Despite his suspicions, no evidence could conclusively support any theory of murder, mutiny, or piracy. The condition of the ship did not support the idea of a violent event, and the crew of the Dei Gratia was eventually cleared of wrongdoing. In fact, their accounts were consistent and credible, and they had conducted themselves properly in towing the Mary Celeste to safety.

In the end, the salvage court awarded a relatively modest sum—just under £1,700—to the Dei Gratia crew, far less than might have been expected for a ship and cargo valued at around £35,000. The reduced award reflected the lingering doubts held by the court, though no formal charges were ever brought.

The salvage hearings cemented the Mary Celeste‘s reputation as a ship shrouded in mystery. The inconclusive nature of the inquiry left the door wide open for speculation, fuelling sensationalist press coverage and public fascination for years to come.

The Life of the Mary Celeste After the Mystery

Although the Mary Celeste became infamous as a ghost ship, her story did not end with the salvage hearings in Gibraltar. After the court’s ruling and the return of the vessel to her American owners, she was refitted and returned to active service. Despite her seaworthiness, the ship never escaped the shadow of her mystery, and a superstition grew around her name. Many believed the vessel was cursed, and sailors grew reluctant to serve aboard her.

Over the following twelve years, the Mary Celeste changed hands numerous times. Her reputation for ill fortune was further cemented by a string of unsuccessful voyages. Several captains and crews reported problems ranging from commercial failure to accidents at sea. Some records suggest that she was underused, chartered mainly for low-value or high-risk cargo that more reputable ships avoided.

By the early 1880s, her commercial usefulness had declined, and the ship fell into the hands of Captain Gilman C. Parker. In 1885, Parker attempted an insurance fraud by intentionally wrecking the Mary Celeste off the coast of Haiti. He filled the hold with a worthless cargo, deliberately ran the ship aground on Rochelois Reef, and then filed a claim for an inflated value.

However, the scheme quickly unravelled. An investigation revealed the fraud, and the insurance companies refused to pay. Captain Parker was arrested and tried, though he avoided a lengthy prison sentence. Nonetheless, his reputation was destroyed, and several individuals connected to the fraudulent venture met unfortunate ends shortly afterwards, adding to the ship’s eerie legend.

The wreck of the Mary Celeste remained where it had been deliberately stranded, gradually breaking apart on the reef. Her once-proud hull, which had inspired such enduring mystery, rotted in obscurity. Yet the legend of the Mary Celeste lived on—spurred by sensationalist newspaper stories, novels, and endless speculation about what really happened to her crew in 1872.

Theories About What Happened

The mystery of the Mary Celeste has given rise to countless theories over the decades, ranging from the rational to the fantastical. With no definitive evidence ever uncovered, speculation has remained a major part of the ship’s legacy.

Mutiny or Foul Play: One of the earliest theories suggested that the crew mutinied, possibly murdering Captain Briggs and his family before fleeing or perishing at sea. However, there were no signs of struggle or bloodshed on board, and valuables were left untouched. The crew had been hand-picked by Briggs and were reportedly trustworthy and experienced, making this theory unlikely in the absence of evidence.

Piracy: The idea of piracy was also considered, especially during the salvage hearings. Yet, again, there was no indication of a violent encounter: the cargo was intact, and there was no damage to suggest a raid. Moreover, piracy was relatively rare in the Atlantic at that time, especially so far from established pirate routes.

Alcohol Fumes Explosion: Perhaps the most widely accepted theory among modern historians is that the ship’s cargo—1701 barrels of industrial alcohol—may have played a role. Nine barrels were later found empty, and these were made of red oak, which is more porous than white oak. It’s been proposed that alcohol fumes may have built up in the hold, creating a risk of explosion.

A small spark or chemical reaction could have caused a loud bang or flash-fire, prompting the captain to order a temporary evacuation in the lifeboat, fearing a larger blast. If the lifeboat had been tethered and the rope broke—or if the sea turned rough—the crew could have been tragically separated from the ship, unable to return.

Waterspout or Natural Phenomenon: Some suggest that a waterspout—a tornado-like column of water—may have struck the ship, damaging her rigging and terrifying the crew. A sudden onrush of water could have made them believe the ship was taking on water rapidly. Fearing imminent sinking, they may have abandoned ship in haste, only to realise too late that the vessel was not fatally damaged.

Poisoning or Madness: Another theory posits that the crew may have suffered from food or water contamination, particularly from ergotism—a condition caused by mouldy grain that can result in hallucinations and irrational behaviour. This could explain an otherwise calm departure in the lifeboat, under a delusion that the ship was doomed.

Seaquake or Submarine Volcanic Activity: Though speculative, some believe an undersea earthquake (seaquake) or volcanic activity may have caused violent shaking, releasing alcohol fumes or damaging the ship’s pump. Such a jolt could have been mistaken for catastrophic structural failure, prompting an evacuation that tragically proved fatal.

Supernatural and Speculative Theories: In popular culture, the Mary Celeste has often been linked with the supernatural. Stories have ranged from sea monsters and giant squids to alien abductions and the Bermuda Triangle—despite the fact that she was nowhere near that region. While entertaining, these theories are based on imagination rather than evidence, yet they have helped cement the ship’s place in maritime legend.

Conclusion of Theories: While none of these theories can be proven conclusively, most maritime scholars today lean towards the alcohol vapour hypothesis or a sudden environmental trigger that led to a cautious but ultimately tragic abandonment. The absence of definitive proof, combined with the seemingly ordinary condition of the vessel, is what has kept the Mary Celeste mystery alive for over 150 years—making it one of the sea’s most compelling unsolved cases.

Leave a comment