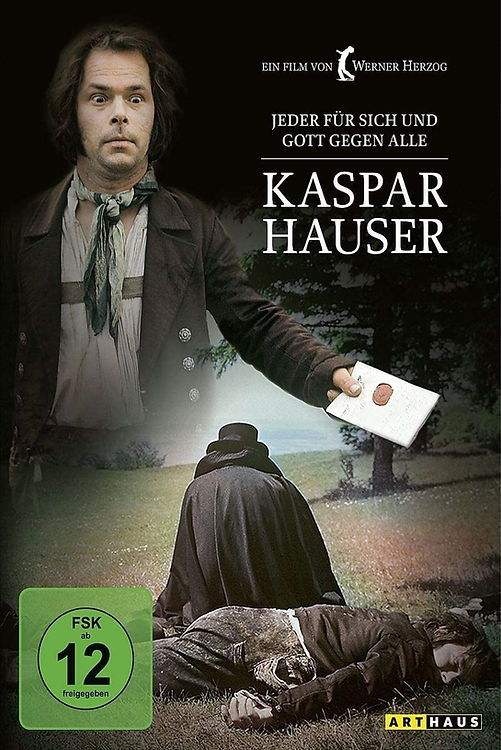

Kaspar Hauser was born on April 30, 1812, and died on December 17, 1833, in Ansbach, a city in the German state of Bavaria. But who was he? This riddle gripped Europe’s imagination in the early 19th century. Was he a wild boy raised in the woods, a victim of abuse and cruelty, a long-lost royal heir or just a crafty fraud?

At the time, hundreds of books, articles, films and even plays were written about him. For about twenty-five years, he was one of the most debated individuals in Europe. Few awoke as great interest and curiosity as the mysterious boy that showed up from nowhere and had no past. The media on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean were full of stories, and many writers and journalists expounded various theories about the boy.

While he was locked up in a jail cell in Nuremberg, many locals attempted to see the “Child of Nuremberg” through his cell window. They wanted to catch a glimpse of the strange boy and his peculiar ways. The news of the boy spread far and wide, and rewards were offered for any information. Investigators scoured the Bavarian countryside searching for the “pit of despair” in which Kaspar allegedly dwelt for most of his life.

The Boy That Showed Up With Two Letters

Around four o’clock on the afternoon of May 26, 1828, a teenage boy appeared in the old medieval centre of Nuremberg, limping and dressed in worn-out clothes and ill-fitting boots. A cobbler named George Weichmann, living by Unschlitt Square, spotted him and attempted to speak to him. The teenager only grunted and handed the cobbler two letters.

The first letter was dated 1828. It was addressed to a captain of a local cavalry regiment named Captain von Wessenig. The unnamed author wrote that the boy was delivered into his care as an infant on October 7, 1812. He noted that he had educated him on good Christian behaviour and taught him to read and write. The author also stated that he kept him isolated and never allowed him out of the house. The letter also said that the boy wanted to be a cavalryman like his father and requested the captain to take him in or hang him.

Another short letter was enclosed, apparently older and addressed from his mother to his caregiver. It stated that his name was Kaspar, that he was born on April 30, 1812, and that his father, a cavalryman of the 6th regiment, was dead. The letter stated that his mother had given him to an impoverished labourer when he was six months old and beseeched the labourer to bring the baby up as his son until he was seventeen. At that age, she instructed the labourer to take him to Nuremberg to join the army.

The cobbler brought the boy to the house of Captain von Wessenig. Once there, they all watched in astonishment as the young man devoured the bread they gave him and drank a whole pitcher of water. He left the ham and beer untouched, however. The boy seemed confused by basic household items; he was scared by the grandfather clock’s pendulum and burnt his fingers on a candle flame.

He could not speak much. His only words were, “I want to be a knight like my father”, and “horse, horse”. If asked further, he only answered he did not know. He could not tell them who he was apart from his name or where he was from.

Kaspar was brought before the authorities in Nürnberg and detained as a vagrant. He was put in the Luginsland Tower in Nuremberg Castle for two months as the leaders had no idea what to do with him. To the astonishment of his charges, he was able to write his name on a piece of paper in captivity.

His caretakers supposed he was about 16 years old. Overall, the boy was in fine physical condition and could walk all 90 steps to his room in the tower. Contemporary records say he had a “healthy facial complexion” but seemed intellectually impaired. Kaspar would sit still without speaking or lying down to sleep for hours in his chamber. He always gravitated to the darkest part of his cell and moved about very quietly. With time the boy started to speak more, and the mayor, Jacob Friedrich Binder, claimed the boy had an excellent memory and was a quick learner.

Eventually, Kaspar started to tell Mayor Binder about his past life. It became clear that Kaspar was not a wild child from the forests as first thought. Kaspar told the mayor how he had spent his entire life locked in a “hole” where he never saw daylight, eating nothing but bread and water. Kaspar told Binder his cell was two by one metres in size and one and a half metres high. He only had a straw bed to sleep on, and his only distraction was two wooden toy horses. He claimed he never saw or heard from anyone.

The boy told the mayor that he found bread and water beside his bed every morning. Sometimes the water would taste bitter, and it would cause him to fall more deeply asleep than usual. When this happened, he found that somebody had cut his nails and hair and changed the straw bed. Kaspar then claimed that the first human being he met was a man who visited not long before his release. The man hid his face but taught him to write his name, stand and walk. He told the mayor that the man had taught him the expression, “I want to be a cavalryman like my father”. Kaspar claimed he did not know what the words meant at the time. The man then brought him to Nuremberg and left him.

This incredible story aroused great curiosity and made the boy an object of international attention. Rumours started circulating that the boy was a lost prince, possibly from Baden, but others stated he was an impostor. Paul Johann Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach, president of the Bavarian Court of Appeals, began investigating the case. The town of Nuremberg formally adopted Kaspar, and people donated money for his upkeep and education. He was given into the care of Friedrich Daumer, a schoolmaster and hypothetical philosopher. With Daumer, Kaspar showed promise as an artist and grew in confidence and knowledge.

Persecution or a Munchausen Syndrome?

If this case was not intriguing enough, several attempts were seemingly made on Kaspar’s life. The last attempt occurred in 1833, five years after his appearance in Nuremberg. On that occasion, he was stabbed to death.

At the time, many suspected Kaspar had manufactured the attacks himself. Cases like this are not unheard of; individuals are known to fake their death, abductions and attacks. Munchausen Syndrome is a mental illness in which a person fabricates or exaggerates symptoms of an illness or injury to gain attention or sympathy. People with Munchausen Syndrome often go to great lengths to create and maintain their false symptoms, including undergoing unnecessary medical procedures, faking lab results, and taking unnecessary medication.

Moreover, it is not uncommon for individuals with Munchausen Syndrome to fabricate elaborate stories about their childhood, including being abandoned or raised by animals, to seek attention or sympathy or make themselves seem more interesting or unique.

Kaspar claimed he was attacked on three different occasions. The first attack, he claimed, was in October 1829. Kaspar said that while sitting on the toilet in Daumer’s cellar, a hooded man attacked and hurt him, leaving a cut wound on his forehead. Kaspar said he recognised the attacker from his voice as the man who had brought him to Nuremberg. The blood trail in the house tells us Kaspar fled from the cellar to the first floor where his room was, but then, rather than looking for his caretakers, he went back downstairs and climbed through a trap door into the cellar.

The authorities in Nuremberg believed the attack was an assassination and moved Kaspar to a safe house in the care of one Johann Biberbach. This episode fuelled rumours that Kaspar could have royal ancestry from Hungary, England or the House of Baden.

However, Kaspar’s story had doubters. Why did he go to his room before going back to the cellar? The sceptics claimed he self-inflicted the wound with a razor and hid it in his room before going to the cellar. The cut was also suspiciously superficial. Kaspar’s caretaker, Daumer, had come to believe that the boy tended to lie. His doubters thought he manufactured the attack to arouse pity and escape scolding for a quarrel with Daumer. The story of this attack is at least suspicious.

Then, on April 3, 1830, a pistol shot went off in Kaspar’s room at the Biberbachs’ house. His attendants hastily entered the room and discovered him bleeding from a wound to the right side of his head. He claimed an attacker had shot him. But Kaspar was alone in the room and could not give any description of the attacker. Shortly afterwards, Kaspar backtracked and claimed that he was trying to get some books, climbed on a chair, fell, and while attempting to find a handhold grabbed a pistol hanging on the wall with the result that a shot went off.

There are doubts about whether the shot caused the superficial wound or was self-inflicted by other means. Some authors connect the incident with a quarrel that broke out because the Biberbach family accused Kaspar of lying to them. Whatever the exact case, this incident led the authorities in Nuremberg to transfer Kaspar in May 1830 to the house of Baron von Tucher. The baron would later also complain over Kaspar’s excessive vanity and falsehoods.

Lord Stanhope and Death

Lord Stanhope, a British nobleman, took an interest in Kaspar and gained custody of him in 1831. He spent a lot of money endeavouring to find out Kaspar’s origin. For example, Stanhope sent Kaspar twice to Hungary, hoping to jog his memory as he seemed to remember some Hungarian words. He had even declared once that the Hungarian Countess Maytheny was his mother.

Kaspar failed to identify any buildings or monuments in Hungary. A local nobleman that met up with Kaspar later reminisced that he found the peculiar boy and his melodramatic demeanour comical. Stanhope later admitted the total failure of his investigations led him to doubt the boy’s story.

In December 1831, Stanhope put Kaspar in the care of Johann Georg Meyer, a schoolmaster in Ansbach. Stanhope, in fact, permanently gave up on the boy. He continued to pay for his upkeep and other expenses but never took him to England with him as initially planned. Many years later, Stanhope published a book discussing the case of Kaspar Hauser. In the book, Stanhope admitted to having been deceived by the boy. Supporters of Kaspar have suspected Stanhope of ulterior motives and working for the House of Baden to squash all rumours linking the boy with them. But later academic historiography has defended the man as a philanthropist, a devout person, and only seeking the truth.

Johann Georg Meyer was a pedantic and rigid disciplinarian. He immediately disliked Kaspar Kaspar’s excuses and evident lies. Their relationship was strained from the beginning. Kaspar got a job as a copyist in a local law office in late 1832. Kaspar was unhappy with his lot in life at that point. He was disappointed not to go to England with Stanhope, and his life went from bad to worse when his patron, Anselm von Feuerbach, died in May 1833. But for his part, Feuerbach had lost faith in Kasper by the end of his life. His family found a note in his legacy where he called Kaspar a rouge and a good-for-nothing that should be killed. We do not know if Feuerbach communicated this change to Kaspar.

Then in December 1833, Kaspar said he was going to the Ansbach Court Garden to meet someone who’d finally give him some answers about his life and who he was. Kaspar later claimed the stranger asked him to confirm his identity before handing him a silk purse, stabbing him and running away. And as before, no one saw the assailant, and Kaspar could not describe him.

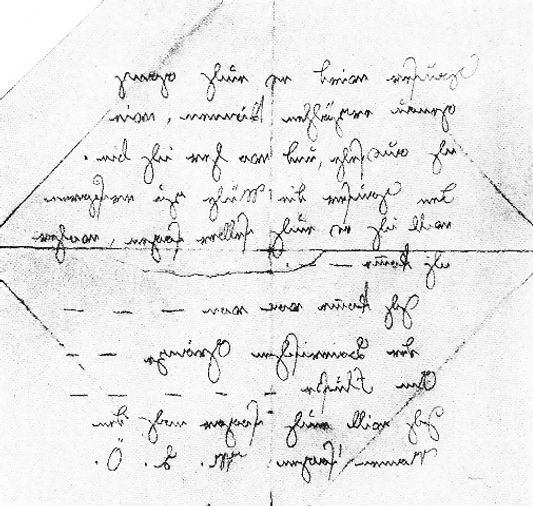

Officials went to the garden and found a small violet purse, as described by Kaspar, containing a pencilled note in Spiegelschrift (mirror writing) but only saw one set of footprints. Inside the bag was a mysterious letter claiming to be from the assailant, mentioning his home town, and signed “M.L.O”. Kaspar died of the wound on December 17, 1833. The attacker was never found.

The death of Kapar is shrouded in suspicion, as multiple pieces of incriminating evidence contradict his claim of being attacked. The nature of the evidence found and what was not found at the scene raises questions about the credibility of his story. It is implausible that an assassin would deliberately leave behind a handwritten note that could be used to identify them later. Adding to the doubt in Kaspar’s account is that there was only one set of footprints in the snow, casting further doubt on his version of events.

The Ansbach court of enquiry was compelled to entertain the notion that Kaspar had fabricated his story of being attacked due to inconsistencies in his account. The discovery of the note inside the purse was replete with spelling and grammatical errors characteristic of Kaspar’s distinctive writing style. Intriguingly, even on his deathbed, Kaspar muttered incoherently about “writing with a pencil”, lending further intrigue to the mystery. Despite Kaspar’s evident eagerness to have the purse located, he made no mention of its contents, which raised eyebrows. Furthermore, the note itself was meticulously folded into a distinct triangular shape, mirroring Kaspar’s known method of folding letters, as confirmed by Mrs Meyer.

Forensic examiners concurred that the wound appeared consistent with being self-inflicted. A prevailing belief among many authors is that Kaspar had deliberately injured himself in a desperate attempt to rekindle public interest in his story and to pressure Stanhope into fulfilling his promise of taking him to England. However, it is speculated that Kaspar may have gone too far, inadvertently inflicting deeper wounds than intended in his ill-fated scheme.

In a 1928 medical study, findings corroborated the theory that Kaspar had indeed inflicted the wound upon himself and inadvertently stabbed himself too deeply. However, a more recent forensic analysis conducted in 2005 presented a contrasting perspective, asserting that it is improbable that the chest stab was solely an act of self-harm. Instead, the research suggested that both suicidal and homicidal possibilities, including assassination, cannot be definitively ruled out.

Who was Kaspar Hauser?

Mental State

Who was Kaspar Hauser? Various theories abound. Some posit that he may have been an undiagnosed epileptic, with some of his claims and visions potentially rooted in medical explanations. Others speculate that the profound neglect and abuse he endured throughout his life may have driven him to delusion and madness, assuming his accounts of mistreatment were indeed true.

During the autopsy, Dr Heidenreich, a physician in attendance, purported that Kaspar Hauser’s brain exhibited notable characteristics such as small cortical size and indistinct cortical gyri, leading some to suggest cortical atrophy or epilepsy as possible explanations, as posited by G. Hesse. However, it is worth noting that Dr Heidenreich’s examination may have been influenced by his phrenological beliefs. In contrast, Dr Albert, who conducted the autopsy and compiled the official report, did not identify any anomalies in Hauser’s brain.

A Prince?

One pervasive conspiracy theory, which emerged as early as 1829, posits that Kaspar Hauser was the rightful heir to a royal throne, kept hidden for some sinister purpose. Proponents of this theory question why the boy would have been subjected to such mistreatment and why several assassins would attempt to kill a teenage boy unless his existence posed a threat to an influential figure.

However, despite its popularity, scholars widely discredit this notion as unlikely. The concept of a mysterious individual of unknown origin who is revealed to be the rightful heir to royalty through the machinations of a powerful conspiracy was not unique to Kaspar, as similar stories and rumours were prevalent in the first half of the nineteenth century. Notably, Alexandre Dumas famously employed this plot device in his novel “The Man in the Iron Mask” in the mid-1800s.

Kaspar Hauser’s one-time guardian, von Feuerbach, believed the boy was of noble birth and publicly expressed this opinion. However, von Feuerbach did not accuse any specific royal house or individuals, and he passed away from an apparent stroke in May 1833. Some conjecture that von Feuerbach may have been poisoned.

Early allegations regarding Kaspar’s origins included claims that he was the hereditary prince of Baden, a region in southwest Germany, and various fanciful stories became associated with his background. One prevalent narrative from the outset was that in 1812, the Countess of Hochberg had surreptitiously swapped the newborn hereditary prince of Baden with a dying infant. Remarkably, this alleged swap was purportedly carried out without the knowledge of the child’s parents or anyone else. The countess was believed to have done so to secure the succession for her sons instead of the rightful prince, whom she sent away to be raised by an impoverished labourer.

In 1876, Otto Mittelstädt presented compelling evidence that countered the prince’s baby swap theory, citing official documents related to the prince’s emergency baptism, autopsy, and burial. It was documented that the mother was too ill to view her deceased baby in 1812, but the father, grandmother, aunt, court physicians, nurses, and others would have seen the baby’s body. Thus, without any credible evidence, it is implausible to suggest that they were all involved in a plot. Furthermore, in 1951 letters from the Grand Duke’s mother were published that provided detailed accounts of the child’s birth, illness, and death, contradicting the theory of switched babies.

Some have speculated that Lord Stanhope, who was involved in Kaspar Hauser’s story, might have known the truth about Kaspar and had a vested interest in keeping it hidden. Others have gone so far as to suggest that Stanhope may have been involved in foul play and had Hauser eliminated. However, such claims remain speculative and lack substantiated evidence.

The Story of Incarceration

Kaspar’s various accounts of his incarceration are riddled with contradictions, as pointed out by psychiatrist Karl Leonhard in 1970. Leonhard stated that if Hauser had truly experienced the conditions he described from childhood, he would not have developed beyond a state of idiocy and would likely not have survived for long. He further argued that Hauser exhibited traits of a pathological swindler, with a hysterical make-up and the persistence of a paranoid personality, enabling him to play his role convincingly.

One well-established fact about Kaspar is that he was a habitual liar. Numerous sources have attested to Hauser’s penchant for exaggeration and tall tales. Kapar fabricated his upbringing when he claimed to have spent his entire life as a prisoner in a dark, isolated room. Had this been true, he would have suffered severe mental and physical debilitation, including likely developing rickets, a bone-softening condition caused by Vitamin D deficiency due to lack of sunlight exposure. However, there are no records of Hauser having deformed bones, which strongly suggests that he had lied about his circumstances.

Furthermore, there were additional discrepancies in Kaspar Hauser’s story. One notable example is a letter he was found with, later discovered as a crude forgery. The letter was addressed to an army captain who was not present in Nuremberg in 1812 when the letter was claimed to have been written. However, he was present a decade later, in 1828, when the letter and Kaspar first appeared.

Examiners determined that the same hand had written this letter and Kaspar’s other letter, which led analysts to speculate that Kaspar himself had written both letters.

DNA Evidence

In 1996, an attempt was made to genetically match a blood sample taken from underwear believed to have belonged to Kaspar Hauser. However, comparisons with descendants of the princely family of Baden, to which Hauser claimed to be related, showed that the blood sample could not have come from the hereditary prince of Baden, casting doubt on Hauser’s claim of royal lineage.

In 2002, scientists conducted further analysis of hair and body cells obtained from locks of hair and clothing items that belonged to Kaspar. Six different DNA samples were extracted from these items, and all were identical. However, these samples differed substantially from the blood sample examined in 1996, raising questions about the authenticity of the earlier sample.

The new DNA samples were compared to the DNA of Astrid von Medinger née von Zallinger zu Stillendorf (1954-2002), a descendant of Kaspar Hauser’s supposed younger sister Princess Josephine of Baden through her granddaughter Princess Joséphine Caroline of Belgium. Although the sequences were not identical, the deviation observed was not significant enough to exclude a possible relationship, as a mutation in previous generations could have caused the difference. However, the relatively high similarity also did not prove the alleged relationship, as the “Hauser samples” showed a pattern consistent with the German population.

Unfortunately, further examination of the remains of Stéphanie de Beauharnais or the child buried as her son in the family vault at the Pforzheimer Schlosskirche has not been allowed by the House of Baden, preventing conclusive results from being obtained from these tests. As a result, the genetic evidence remains inconclusive in determining Kaspar Hauser’s true lineage.

Was he a Fraud?

Critics of Hauser have raised doubts about his story, suggesting that he may have been a clever con artist or, at best, an unfortunate victim of unscrupulous fraudsters who sought to exploit the notoriety of the case.

Kasper’s claims of never leaving a dark room for 16 years and surviving on bread and water alone are inconsistent with descriptions of him as a broad-shouldered lad with a healthy complexion. The speed at which he started talking, reading, and writing has also raised suspicions for some. Furthermore, his prison or prisoners were never found.

Despite these inconsistencies, many in Nuremberg hesitated to question Kaspar’s story, as it had quickly gained international attention and was seen as something fortune that should not be doubted.

This reluctance to scrutinise Kaspar’s claims may have contributed to the sensationalism surrounding the case and the challenges in accurately determining the truth behind his mysterious background.

Given Hauser’s falsehoods about both the beginning and end of his life, it’s challenging to trust any of his claims about his life as being truthful. The most compelling evidence suggests that much of the mystery surrounding Kaspar Hauser may have been manufactured by Kaspar himself, either as a hoax or due to a mental illness. His motives remain unknown, but it’s clear that he sought and relished his international notoriety, as he eagerly sought and enjoyed being famous.

Whether Kaspar was a con artist or a genuine enigma, he ultimately succeeded in leaving a lasting legacy. His true nature and identity are still debated and discussed today, nearly two centuries after his birth. Perhaps one day, the truth about Kaspar Hauser will come to light. Still, for now, he remains a captivating enigma whose story intrigues and puzzles historians and researchers alike.

Leave a comment