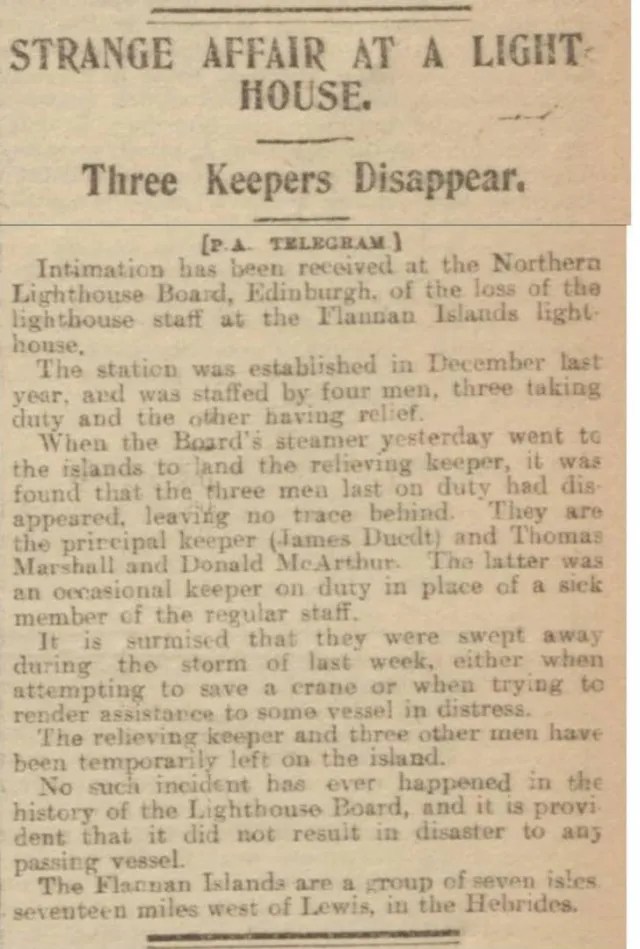

Head Keeper James Ducat (aged 43) arrived at the lighthouse on the island of Eilean Mòr on December 7th, 1900, to begin yet another tour of duty. He had temporarily lost his First Assistant, William Ross, to illness, and a local man, Donald William McArthur (aged 28), took his place. McArthur was only a lightkeeper on occasion when regular members of the crew were unavailable. The third person to make up the party was the Second Assistant, Thomas Marshall (aged 40).

With the trio on the relief boat was Robert Muirhead, superintendent of the Northern Lighthouse Board. Muirhead was a hands-on supervisor and liked to go regularly to the island to inspect the lighthouse and check the work of his subordinates. He spent some time on the island, making sure everything was in order, and then shook hands with each of the three keepers and wished them a pleasant stay on the isolated island. He returned to the waiting boat, which brought them and waved goodbye. It was the last time anyone saw the men.

What happened is one of the most enduring mysteries of recent history. Why did they vanish without a trace ten days before Christmas in 1900?

The Islands and the Lighthouse

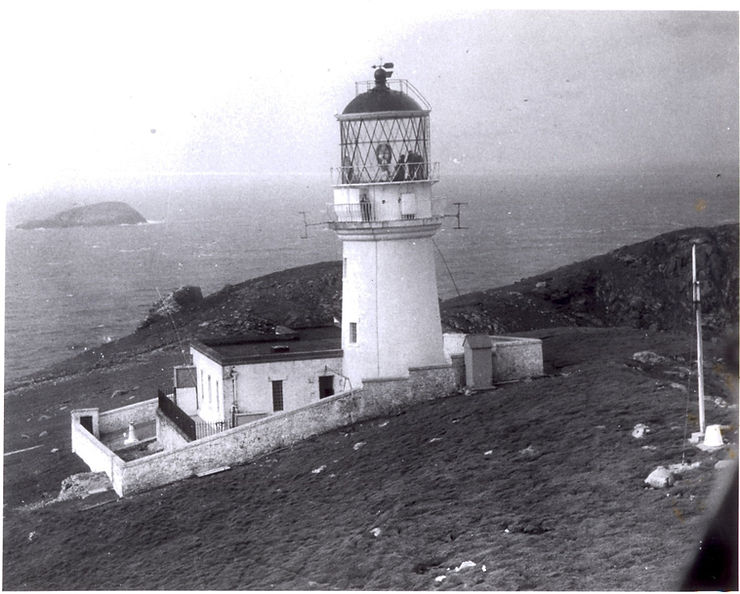

Eilean Mòr is the largest (about 43 acres) of the so-called Flannan Islands, a group of seven tiny uninhabited islands in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, 32 km west of the large Isle of Lewis. Flannan Islands are sometimes also called the Seven Hunters. The islands are reputed to take their name from Saint Flannan, the 7th-century Irish preacher and abbot. No permanent residents have been on the islands since the Flannan Isles Lighthouse on Eilean Mòr was automated in 1971. Only the odd visitors stop there now to explore the island and the ancient chapel.

For centuries the island has been feared by the locals. It has been over a thousand years since anyone has lived there permanently, at least not since Saint Flannan reputedly lived there with his Celtic flock of followers. Occasionally shepherds brought sheep to the island to graze. They would never stay overnight as they feared the spirits thought to haunt that remote spot.

There are only two structures on Eilean Mòr. One is an old stone chapel that is said to have been built by the aforementioned Irish abbot Saint Flannan in the 7th century. The second structure is the lighthouse, built in 1899. Construction on the 23-metre-high lighthouse began in 1895 and took twice as long as planned due to adverse weather and rough seas. The building work finished in December 1899. Remarkably, the lighthouse keepers lighted it for the first time on December 7th, exactly a year before superintendent Robert Muirhead waved goodbye for the last time to the trio of keepers on the island.

No Lights

The standard practice was to keep the island under periodic observation from Gallen Head on the Isle of Lewis by telescope. This practice was most straightforward by night as the light from the lighthouse was more visible then. In an emergency, the keepers had instructions to raise a flag, and a rescue boat would be dispatched to the island.

This observation system had severe shortcomings as the lighthouse was often obscured by mist, and there was no guarantee that the observers could see anything from the mainland. In the case of our story, the observer, Roderick McKenzie, did not notice anything amiss. The lighthouse beam was seen on December 7th and then again on December 12th, and even then, it was barely visible. Thick mist and clouds hid the islands from view. In fact, the lighthouse would not be visible again from land until December 29th (three days after the island was found deserted).

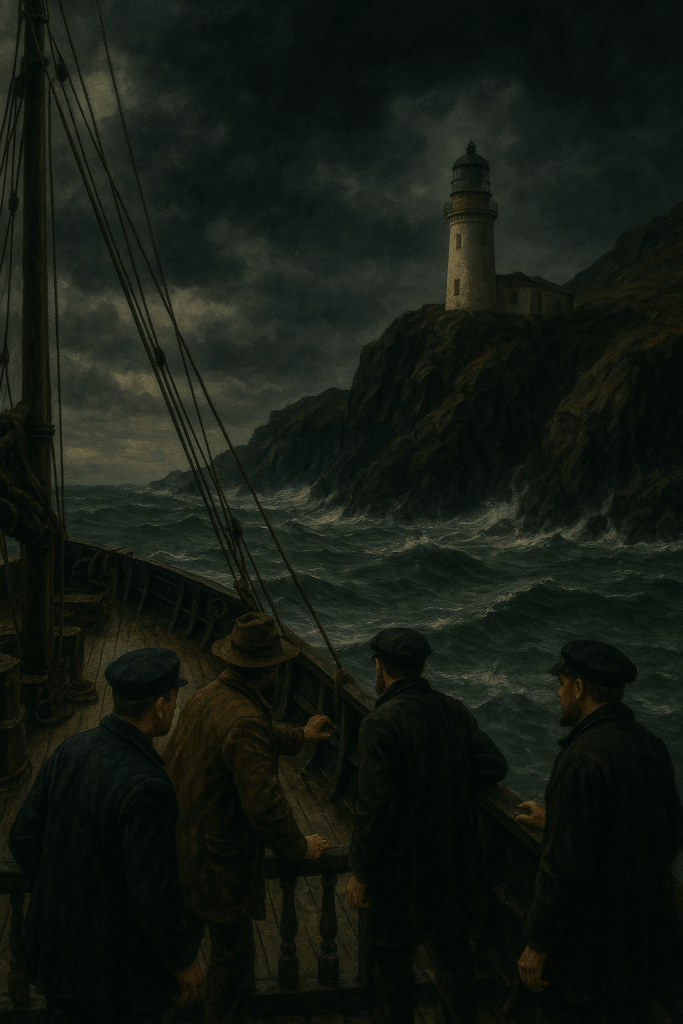

The first sign of something being amiss came on December 15th. The steamer SS Archtor, on its way from Philadelphia to Leith, passed the Flannan Islands close to midnight and the sailors onboard noticed that the lighthouse beacon was not operational. They were close enough to the island and should have seen the light, but everything was pitch dark. The ship’s captain sent a message through the wireless to Cosmopolitan Line Steamers HQ. However, they overlooked reporting the fact to the Northern Lighthouse Board; therefore, no action was taken.

The Arrival on the Island on Boxing Day

The relief ship, the lighthouse tender Hesperus was due to sail from Breasclete on the Isle of Lewis on December 20th, but due to adverse weather conditions, it departed on December 26th, on Boxing Day.

They suspected something was wrong on arrival at noon, even before they anchored. Jim Harvie, the captain of Hesperus, blew his ship’s horn and sent a warning flare to attract the attention of the three keepers. Still, the only response was an ominous silence and the occasional cry of a seabird.

The relief keeper, Joseph Moore, was put ashore alone. With no one to assist them from the landward side, it took a lot of work to pull up the boat. Moore himself had to jump ashore to grab the mooring rope and throw it aboard.

Moore later said he found an overwhelming foreboding when climbing onto the island. None of the lighthouse keepers welcomed him ashore, as was their custom. It was also a tradition to flag for the relief boat to acknowledge they noticed it coming. On this occasion, he found the flagstaff without a flag and none of the usual provision boxes on the landing stage ready for restocking.

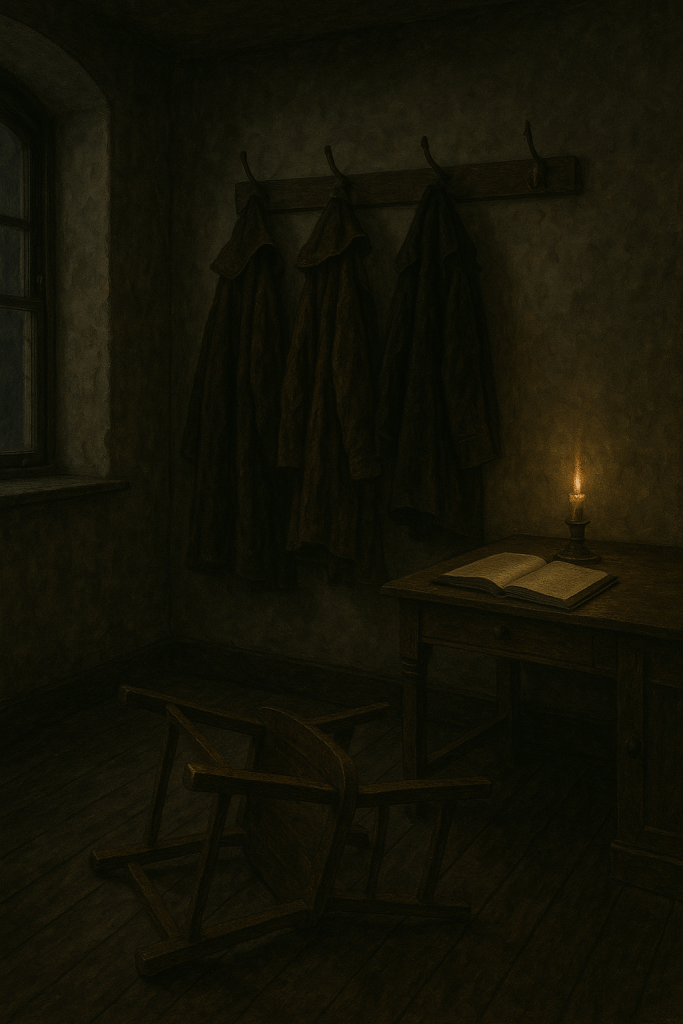

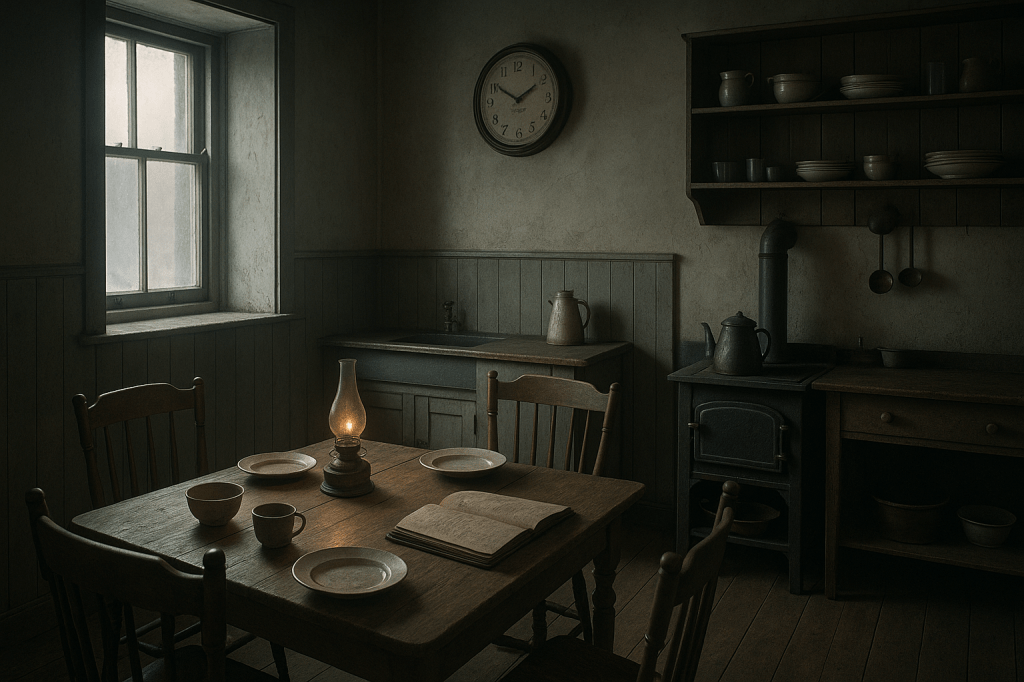

Moore also found the entrance gate and the main door of the lighthouse complex closed. When inside, he found the beds unmade and the clock unwound. The kitchen also revealed an overturned chair and the remains of a half-eaten meal.

He then returned to the landing stage with the grim news. A second mate and a seaman from Hesperus returned with him for a further search. There was no sign of the keepers inside the lighthouse or on the island. An examination of the lighthouse revealed that the lamps had been cleaned and refilled. They found a set of oilskins that indicated one of the keepers had left the shelter of the lighthouse without them. Despite the cold winter weather, there was no sign that a fire had been made for a week or so in the grate.

After the search and night fast approaching, Captain Harvie could not investigate further. He returned to the Isle of Lewis on Hesperus and left Moore and three seamen on the island to operate the lighthouse. To stay there on the island after this mysterious disappearance of their mates must have been nerve-racking. Going to bed that night must have been hard. What happened to the men?

When Captain Harvie arrived in the evening on the Isle of Lewis, he sent a telegram to the Northern Lighthouse Board. In it, he described what met them on arrival, the search, and the state of things inside the lighthouse and concluded that all signs indicated to him that the misfortune must have happened about a week before they arrived. He stated:

Poor fellows they must been blown over the cliffs or drowned trying to secure a crane or something like that.

The men left behind on Eilean Mòr used their time to explore every nook and cranny on the island. They found the east landing intact, but the west landing provided substantial evidence of damage caused by recent storms. They discovered bent iron railings and the iron railway wrung out of the concrete used to fasten it. The storm had displaced a rock, approximately one ton in weight. The weather had also blown away a storehouse, and some ropes usually stowed safely away were stuck on a crane 25 metres above sea level. And on the top of the cliff (60 metres above sea level), the tempest had ripped away the turf as far inland as 10 metres from the cliff’s edge.

The Investigation

Therefore, as Joseph Moore and the others could make out, everything had been running smoothly on the island until the afternoon of December 15th. Accurate record-keeping was mandatory for all lighthouse crew, and the Head Keeper, James Ducat, had conscientiously compiled reports up until the 13th. The lighthouse keepers had written draft entries for the 14th and 15th of December on a slate. Whatever had happened to the three men, it had happened to them that afternoon.

On December 29th 1900, Robert Muirhead, a Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) superintendent, joined the others on the island to conduct the official investigation into the incident. Muirhead initially recruited all three of the missing men and knew them personally. His official report is the most detailed account of the island’s state at that time.

In the report, Muirhead ponders the question of the clothing left behind in the lighthouse. He concludes that Ducat and Marshall went to the western landing, and McArthur (the substitute lightkeeper) left the lighthouse in his shirt sleeves during heavy rain. He comments that whoever left the lighthouse last was in breach of the rules as it was not allowed to leave the light unattended.

The storm on the night of December 14th caused substantial damage. Muirhead points out that some of the damage to the west landing was “difficult to believe unless actually seen”. He was convinced that the men had been on duty until dinner on Saturday, December 15th. He concluded they had gone to secure a box full of mooring and landing ropes. This box was fastened in a crevice in the rock about 34 metres above sea level.

Muirhead believed they had either been blown off the edge or a large wave swept over them and dragged them out to sea. However, as the wind was in an uphill direction, it was unlikely that the men had been blown off the edge. Therefore, Muirhead concluded that a freak wave was ultimately responsible for the men’s disappearance.

The report did not convince some members of the Northern Lighthouse Board. They had several questions they felt the investigation did not answer. They questioned why one of the lighthouse keepers left without his oilskin coat or why no bodies washed ashore. And why had all three men left their posts at the same time? Was it plausible that three skilled keepers would be surprised by a wave?

But the biggest question was regarding the weather. According to the record in the lighthouse, the weather had blown over on the morning of the 15th. The board members were sure the weather was still calm in the evening simply because they could see the lighthouse from the mainland. In the case of a storm, this was not possible. And if the weather was calm on the evening of December 15th, how did the giant wave come about?

The Logbook

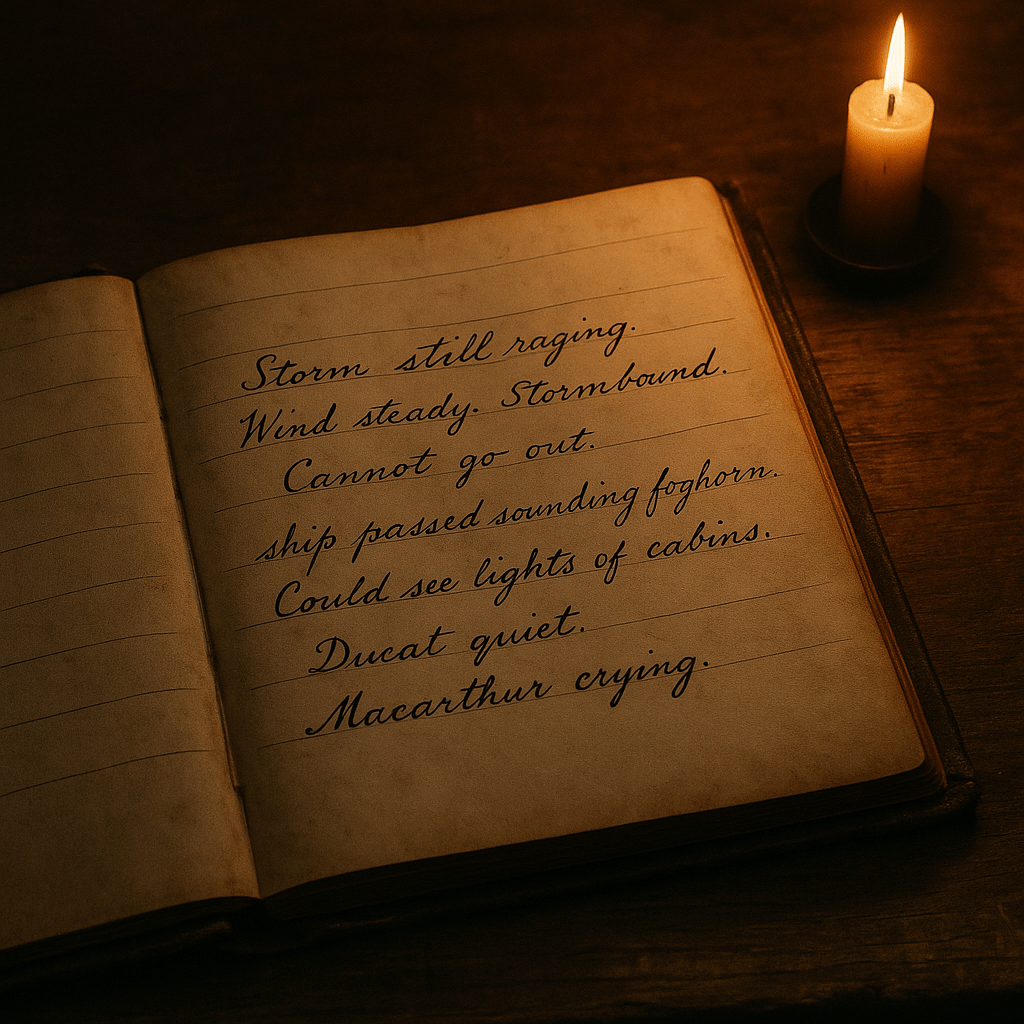

The logbook is one of this story’s most famous and long-lived components. Entries in the logbook have lent the story its mystery and indicate the men disappeared by supernatural means.

According to the tale, Robert Muirhead started his investigation by inspecting the lighthouse logbook. The entries in the log indicated unusual and, indeed, extreme weather conditions. The entry for December 12th, supposedly written by second assistant Thomas Marshall, reported “severe winds the likes of which I have never seen before in twenty years”. The entry says Ducat was irritable and that the tough third assistant Donald McArthur had been crying. It sets a mysterious and scary mood,

Storm still raging. Wind steady. Stormbound. Cannot go out. ship passed sounding foghorn. Could see lights of cabins. Ducat quiet. Macarthur crying.

On December 13th, the log says,

Storm continued through night. Wind shifted west by north. Ducat quiet. Macarthur praying. 12 noon. Grey daylight. Me, Ducat, and Macarthur prayed.

Indeed scary stuff. Oddly, nothing is recorded on December 14th, but on the 15th, the log says,

1pm. Storm ended. Sea calm. God is over all.

Strangely, and entirely at odds with the log, no storms were reported in the area for the 12th, 13th or 14th. Storms were only reported from the 17th onwards, which prevented the Hesperus from sailing on time to the island to relieve the lighthouse keepers. There’s no evidence of extreme weather on the Isle of Lewis on those dates. Therefore it is improbable the weather was terrible on Eilean Mòr.

Simply put, the reported log entries do not fit the facts. There was no bad weather when the log said there was. The entries also supposedly stated that Ducat had been “very quiet” and Donald McArthur had been crying. These entries do not fit the known character of the men. McArthur was an experienced sailor with a reputation for brawling. It would be out of character for him to cry in response to a storm. The entry on December 13th also states that all three men had been praying. This sentence is also baffling, as all three men were experienced lighthouse keepers in a secure structure 45 metres above sea level. It is doubtful they feared for their lives in that environment.

Mike Dash of Fortean Studies has investigated the reported logbook with more critical eyes than others. According to his research, Vincent Gaddis, a well-known writer of the 1960s, first mentioned the existence of the logbook. Gaddis stated he found the information in an American magazine called True Strange Stories in August 1929.

Dash managed to get his hands on a copy after years of looking. And indeed, the magazine was the source of the mysterious log entries. The author of the article insisted the details of the log were from “English sources” but gave no further detail or proof of where he got them. There was no requirement for him to provide more evidence as True Strange Stories was not an accurate history publication but a sensationalistic storytelling magazine.

According to Dash, large chunks of the story about the lighthouse keepers told in the magazine were either heavily fictionalised or entirely wrong. The story’s author, Ernest Fallon, did probably not even exist. No other article is credited to him, and his name appears nowhere else in pulp magazines or Fortean phenomena literature. It was not unusual for True Strange Stories to publish articles under fake names. It is most likely the story (and therefore the entries) was just entertaining fiction.

Mike Dash makes several other points to support his conclusion. He points out it is most likely the men were out working in the storm and met with some accident. But this is neither thrilling nor mysterious. The logbook’s entries help set a more exciting scene. The entries indicate their disappearance happened after the storm had passed. This suggests some supernatural event. Someone likely penned the entries to make the story more appealing to readers.

Dash also rightly points out that the entries do not match the writing rule of nautical logs. Such logs are not supposed to be diaries full of the impressions and feelings of a particular writer. They are precise records of events written by a changing rotation of officers. There is no space for sentimental observations. The log was supposedly written in the hand of the young Third Officer, Thomas Marshall. Dash states it is unlikely that Marshall would allow himself to make such notes in a log that his superiors would read.

Dash remarks it is evident after careful reading that the entries were written after the event and are, therefore, fiction. Why would Marshall, for example, make a special note about Ducat being quiet? It was common for men in this line of work and not worth noting in an official record. In the hands of sensational writers through the years, the entries indicate that the men were conscious of some imminent supernatural catastrophe. Dash, however, believes the opposite: Ducat’s and MacArthur’s moods, as recorded on December 12th and 13th, only have significance because of the events on December 15th. This indicates someone created the entries after the event to create a better mystical story.

And then there is the timing of the entries. Details from the Northern Lighthouse Board archives and contemporary newspapers make it clear the lighthouse keepers only kept the log until December 13th, and subsequent entries were written in chalk on a slate for later transfer to the book. Dash states that the notion of logbook entries from as late as the afternoon of December 15th is false.

Dash notes that even though we count the writing on the slate as part of the logbook, the last entries were about the weather, written at 9 am on December 15th. Nothing was written at 1 pm, as stated in True Strange Stories. The entries are, therefore, obviously a hoax.

The Northern Lighthouse Board doesn’t have copies of the original logbook. The documents regarding the incident are held by the National Archives of Scotland but do not include a logbook. These famous entries are nowhere to be found.

Theories Through the Years

In a first-hand account made by Moore, the relief keeper, he stated that the kitchen utensils were clean, which was a sign they left the lighthouse sometime after dinner. However, in 1912, Wilfrid Wilson Gibson composed the ballad “Flannan Isle”. In it, he refers erroneously to an overturned chair and an uneaten meal on the table, indicating that the keepers had been suddenly disturbed.

The piece lacked historical accuracy but created a disturbing sense of danger and uncertainty. In many ways, this work captured the public’s imagination rather than the actual events. It has inspired music and fiction and the inevitable alternative theories. Let’s look at a few of them.

Jim Harvie, the captain of Hesperus, believed the men had disappeared on December 20th as it was the date the clock stopped in the lighthouse, and there were severe storms in the area on that day. The argument against this theory is that nothing was written in the logbook after the 15th, and clocks usually go on for many days after being wound up.

Another theory is that the mean drowned at the western landing. The coastline of the island is deeply indented with narrow gullies called geos. The west landing, situated in such a geo, terminates in a cave. In high seas or storms, water would rush into the cave and then explode out again with considerable force.

Marshall was previously fined five shillings when his equipment was washed away during a huge gale. In seeking to avoid another fine, maybe he and Ducat tried to secure their equipment during a storm. McArthur may have seen a series of enormous waves approaching the island and, knowing the likely danger to his colleagues, ran down without his oilskins to warn them, only to be washed away in the violent swell. This theory also explains the oilskins remaining indoors and McArthur’s coat remaining on its peg. This theory does, however, not explain the closed door and gate.

But would three experienced lighthouse keepers have been caught up in such an event? They would have been perfectly aware of any potential dangers and surely not left the security of the sturdy lighthouse during the height of a storm, except in an emergency. They would surely have waited for the storm to go out before venturing outside.

Another theory is based on the first-hand experiences of Walter Aldebert, a keeper on the Flannan Isles, from 1953 to 1957. He believed one man might have been washed into the sea, and his companions, who were trying to rescue him, were washed away by more rogue waves.

Then there is the theory they went to the relief of a vessel in trouble offshore and either drowned or went away with it. But nothing was ever reported about a lost ship or vessel in trouble in the area.

Then there are the theories that we must count as more unlikely. One is that the three men decided the island was too cold and inhospitable and decided to start a new life elsewhere. They boarded another ship and left for good. This theory has many flaws. They all decided they wanted to go at the same time? Where did they board a ship at this desolate place? All these men were highly dependable. Two of them were married with families and wouldn’t be considered likely candidates—perhaps one, but not all at the same time.

Then there is the abduction angle. A theory says they were abducted by a ship containing foreign spies or kidnappers. This idea is very far-fetched, especially as there were no wars at the time. Then there are the theories of abduction by spirits or otherworldly beings on UFOs. Even though we can never prove this not to be the case, this is also far-fetched. One tale has a sea serpent carrying them away, and one says they met their fate through the malevolent presence of a boat filled with ghosts.

One theory states that one of them went crazy and murdered the other two and subsequently committed suicide by jumping into the ocean. Another approach is based on the psychology of the keepers. Allegedly, McArthur was a volatile character; this may have led to a fight breaking out near the cliff edge by the West Landing that caused all three men to fall to their deaths.

Today, no one seriously disputes the findings of Superintendent Muirhead. It was most likely not aliens or sea monsters that killed the unfortunate Keepers of Flannan Island – it was the Atlantic Ocean, in one way or another.

Leave a comment