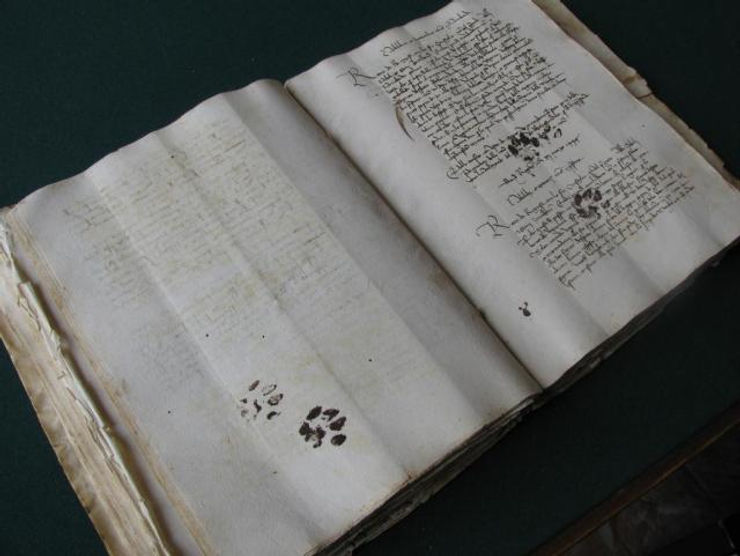

Everyone knows about the independence of cats. Animals that laugh at our human notions that someone actually owns them. Those who “own” cats are well aware of their disregard for our rules, peeing where they see fit and walking over things that shouldn’t be walked over. This is clearly nothing new. Erik Kwakkel, a professor of palaeography, posted a photo on Twitter of an old manuscript in which a cat had taken a walk on its owner’s manuscript:

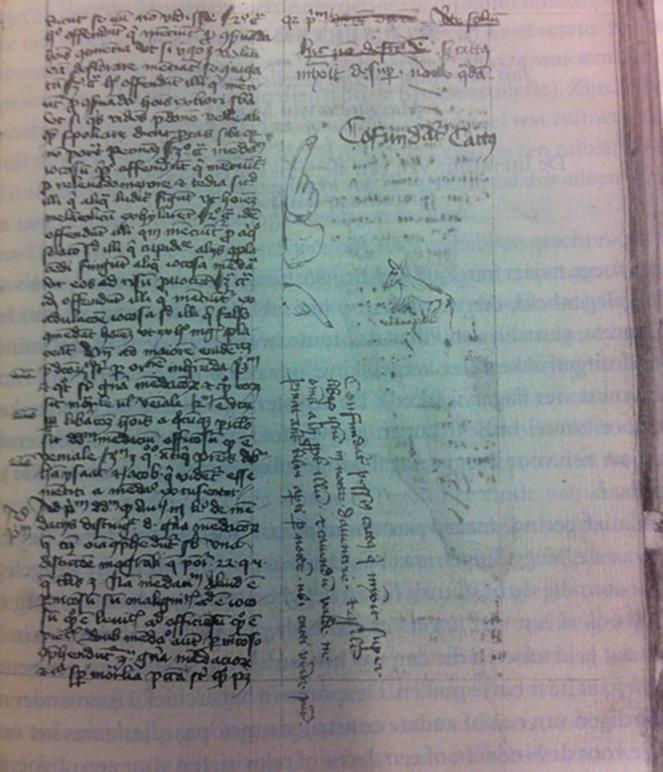

But this is not the only example of cats vandalizing manuscripts. Sometime around 1420, a scribe in Deventer in the Netherlands, found his manuscript damaged after a cat used the open manuscript as a toilet at night. The next day, the scribe was forced to leave the rest of the page blank and continue with the text on the next page. Not only that, he drew a picture of the cat and a finger pointing to the pee spot. Beneath the pee patch he wrote an angry curse:

Hic non defectus est, sed cattus minxit desuper nocte quadam. Confundatur pessimus cattus qui minxit super librum istum in nocte Daventrie, et consimiliter omnes alii propter illum. Et cavendum valde ne permittantur libri aperti per noctem ubi catti venire possunt.

Roughly translated this means:

This is not a flaw in the script. A cat urinated on the script at night. Curse on the bad cat who urinated on this book overnight in Deventer, and also all other cats because of him. Be careful not to leave books open at night where cats can get to them.

Why did they have cats in libraries amidst all the valuable beautiful books? The answer is simple, the cats were there to chase mice, rats and other unwanted animals. They were simply the best defence possible. The manuscripts in the dusty libraries of the Middle Ages were an exciting prospect for mice and rats.

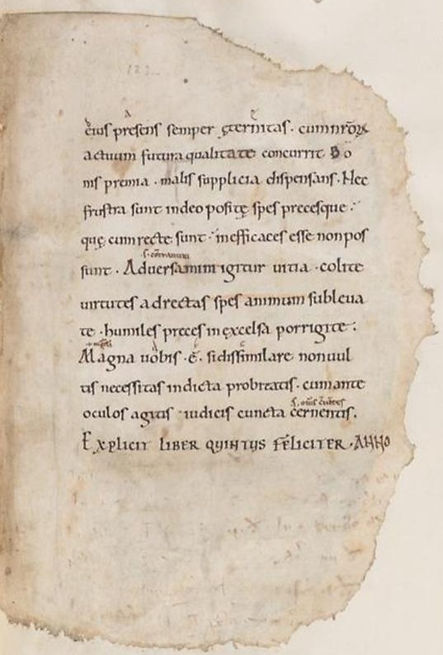

This can be seen, for example, in this manuscript from the eleventh century. This copy of Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae clearly shows teeth marks from mice or rats.

In addition to destroying manuscripts, the rodents were often unpopular for disturbing the scribes at work and stealing their food. And although cats had a tendency to soil the manuscripts, the advantages of their presence outweighed the disadvantages.

Finally, here is a poem from the ninth century (modernised) written by an Irish monk about the cat Pangur Bán, which shows in a fun way the role and importance of cats in the bookmaking of previous centuries:

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

‘Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

‘Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill-will,

He too plies his simple skill.

‘Tis a merry task to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur’s way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

‘Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

‘Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

When a mouse darts from its den,

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!

So in peace our task we ply,

Pangur Ban, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

The poem was translated from the original by Robin Flower. See here.

The above material about cats and mice is largely borrowed from the writings of Thijs Porck, a lecturer at the Department of English and Culture at Leiden University.

Leave a comment