El Raval

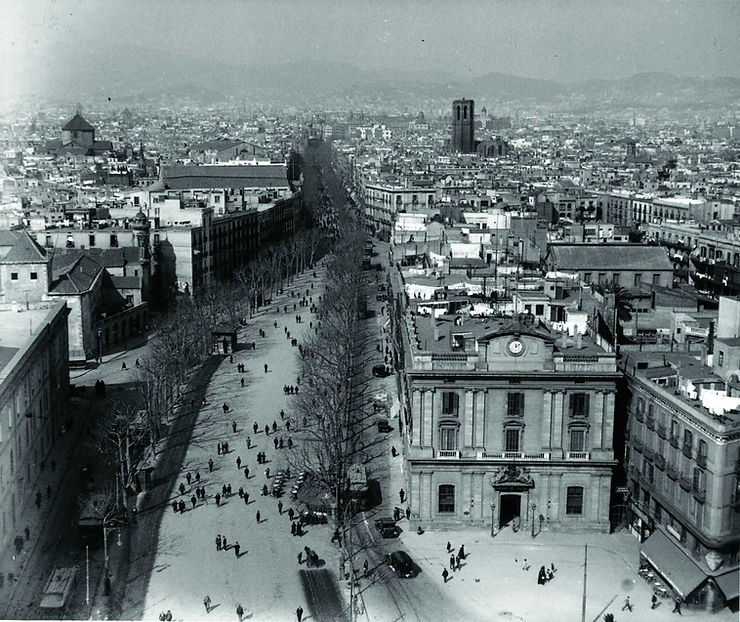

We are in the El Raval district of Barcelona a few years before the First World War. El Raval is the second oldest district of the city, along with the Gothic quarter located across the city’s main street, la Rambla. The neighbourhood had been the centre of industry in the town in the 19th century. But after the city authorities began to develop the l’Eixample district north of El Raval, the district’s importance decreased, and it fell into decline.

The neighbourhood is old and has narrow streets. The inhabitants, who are manual workers and immigrants, live very close together. At the beginning of the 20th century, the district is the most densely populated urban district in Europe. The residents live in poorly built apartment buildings where petty crime, drugs and prostitution are rampant. The area is home to liberal artists and is full of theatres, brothels, bars and cabarets. The neighbourhood is a hideout for anarchists, communists and others who want to keep a low profile. The district is notorious, and it is not until the end of the 20th century that other citizens of Barcelona think of entering the neighbourhood.

Disappearing Children

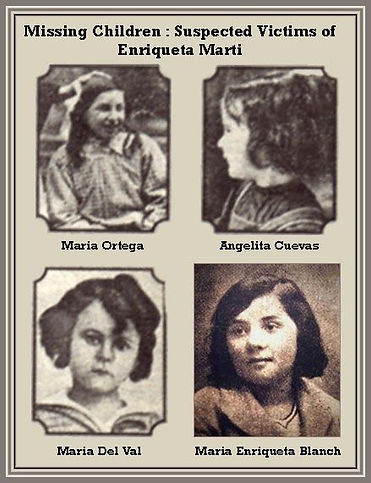

In the first decade of the 20th century, terrible things are happening in El Raval that no one talks about. Children regularly disappear and are never seen again. Most of the people of Barcelona don’t care because these are poor and helpless children.

The children continued to disappear until February 1912, when a woman named Enriqueta Martí i Ripollés was arrested and suspected of child abduction. Then finally, the child disappearances were given attention in the media. As the police dug deeper, the case turned from simple child abduction to a series of child abductions and mass murders. The press began to call Martí “The Vampire of Raval”, “The Vampire of Barcelona,” or “The Vampire of Pontentgatu” after the street where she was arrested.

The police unearthed many cruel things about Martí’s actions in the following days and weeks. She was accused of abducting and killing a large number of children over twenty years. It is difficult to assert the actual number of children who were her victims. During interrogation, Martí confessed to supplying children for rich child molesters, but she denied having killed anyone. She was never tried because her fellow inmates killed her before the trial.

Enriqueta Martí

Enriqueta Martí was born in the town of Sant Feliu de Llobregat in 1868. Today, the town is one of Barcelona’s suburbs, 12 km from the city centre. Nothing is known about her childhood or her family. We don’t know when or why she moved to Barcelona, but we do know that as a young woman, she worked as a waitress and nanny. But life was hard in the big city, and it wasn’t long before she started working as a prostitute.

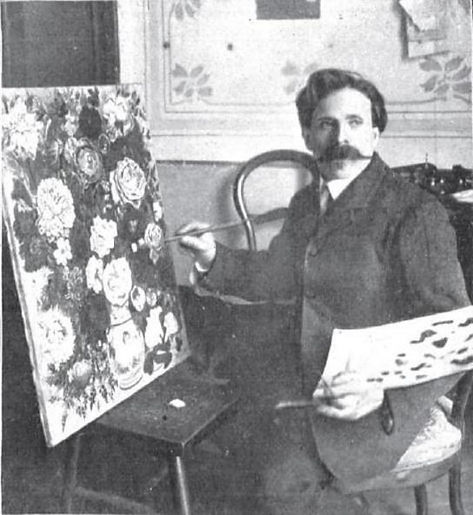

We know she married the painter Juan Pujaló in 1895, but the marriage was childless and unhappy. The ex-husband didn’t speak well about her later, and according to him, they divorced because Martí cheated constantly, was difficult to get along with and continued to work at the brothels. The marriage was stormy, and they separated and reconciled about six times. When she was arrested, they had been divorced for five years.

In 1909 Martí founded her own company, a brothel for the city’s wealthier residents. Martí did not hesitate to make various unusual wishes of her clients come true for a higher fee. Among them were customers who requested sexual activities with children.

She put in a lot of effort to provide children for her clients. She dressed as a poor woman during the day and visited the poorest of the poor in the city. She begged and stood in lines with the poor at the convents to receive alms. When she came across children not attended to by adults, she kidnapped them and sold them in her brothel. At night she dressed up and went to the theatres and casinos of the rich to form relationships with the morally twisted of the upper class.

The Witch Doctor and Her Arrest

Martí also had another job. She was a witch doctor. Martí sold creams and potions to stop ageing and prolong life. The ingredients often came from children she killed. She used the children’s fat, blood, hair, and bones in her products. She also claimed that drinking children’s blood could cure tuberculosis, a significant threat at the time. Wealthy citizens of Barcelona paid handsome sums for her medicinal drugs. What did it matter to them if some poor children were sacrificed?

Martí was arrested in July 1909 in her home, accused of running a brothel where children were sold. She was never formally charged because she exploited her connections with her wealthy and powerful benefactors in the city, and the case was dropped. The police had little interest in the fate of poor children, many of whom had poor parents or were simply orphans. Penalties for crimes against children were very light at the time. Raping a girl or boy costs a fine of fifty pesetas, half a month’s wage of a worker.

It wasn’t until three years later, in 1912, that Enriqueta was finally stopped. For two weeks, authorities had been looking for a girl named Teresita Guitart Congost. Her parents were not wealthy, but her father was popular in the city. The city authorities were under pressure to find her, as people had long criticised them for doing little in the case of missing children. The disappeared child had parents of note this time, and the search began in earnest.

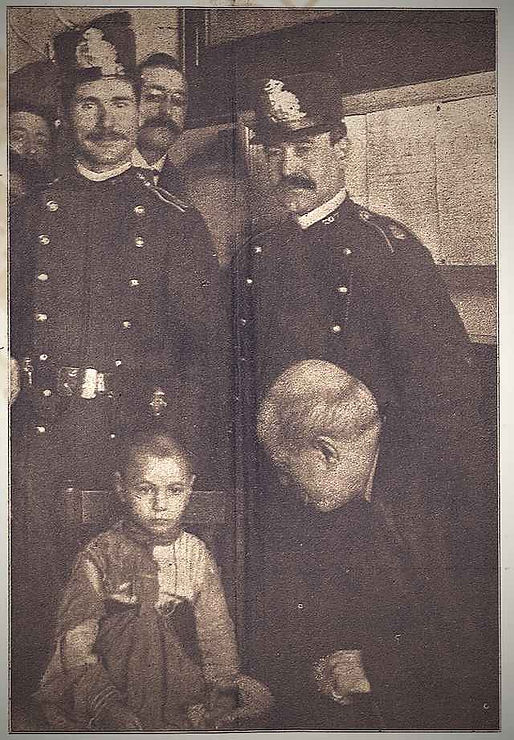

But it wasn’t the police who tracked down Teresita. A neighbour saw a girl in a window at Martí’s house at 29 Pontent Street. She did not recognise the girl as someone who lived there, and she notified the authorities. When the police arrived, there were two girls in Martí’s apartment. One was the lost Teresita, and the other was called Angelita. Teresita was returned to her parents. She told authorities that Martí had lured her in with the promise of sweets and locked her up. The girl also reported that she came across a bag with children’s clothes and a bloody boning knife at Martí’s house.

The other girl in the apartment did not know her last name, so it wasn’t easy to find her parents. Martí claimed that Angelita was her daughter with her husband, Juan Pujaló. However, Pujaló himself asserted to the police that they had no children, and he did not know who the girl was. Angelita’s account was even shadier. She told the police that she saw Martí kill a five-year-old boy called Pepito on the kitchen table on Pontent Street.

The Investigation

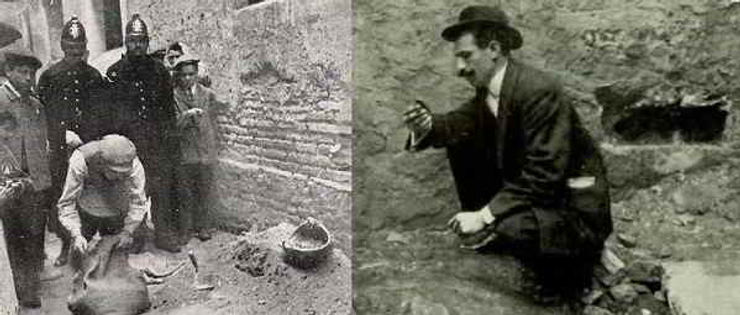

During a search, the police found the bag that Teresita had told them about. They also found another bag with dirty clothes and at least thirty small human bones. What attracted the most attention was that, although the apartment smelled bad and was poorly furnished, one living room was elegantly furnished. In it were found elegant clothes for girls and boys. The police concluded that the clients had been brought in there. In a locked room, about fifty jugs, jars and bowls were found with remains of human bodies, fat, coagulated blood, children’s hair, skeletons and powdered bones. The police also found containers with drinks and ointments ready for sale there.

The investigators also searched other apartments and houses where Martí had previously lived. Body remains were found in the walls and ceilings. In the yard of one of the houses, a skull of a three-year-old child was found, and other bones matched three, six, and eight-year-old children. The child clothes the police found in its search confirmed that all the children were from low-income families that probably did not have the means or conditions for an extensive search.

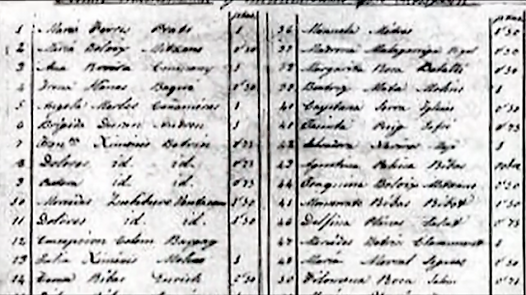

Various strange objects and recipes were found, but what attracted attention was a list of rich and important people in Barcelona. The public believed it was a list of Martí’s wealthy clients. In their opinion, people on the list bought children from her to molest or purchased her medicinal concoctions. To calm the public, the police launched a massive campaign in the newspapers to say that the list was just a list of people Martí had either begged money from or tried to swindle. It is impossible to know for what purpose Martí made the list.

All in all, forensic pathologists could identify the remains of twelve different children with the little evidence they were able to salvage. It is impossible to say with any certainty how many victims there were.

Martí Speaks

During interrogation, Martí proclaimed that she was studying anatomy but soon confessed that she was a witch doctor and used children as ingredients for her medicines. She disclosed the location of other apartments and told investigators where to search them. She also admitted to providing children to abusers but did not name a single client by name.

Martí could not properly explain who the young boy was that Angelita saw her murder on the kitchen table. And she couldn’t explain what had happened to him either. A woman from Alcañiz came forward and identified Martí as her child’s kidnapper six years earlier. Martí had shown the woman exceptional kindness when she arrived in Barcelona after a long journey. The woman was tired and hungry and allowed Martí to hold her baby. Martí disappeared with the baby, and the woman never found Martí or her son again. It was supposed that Martí used the child to produce her medicines. Martí confessed to many things, e.g., having sold children into prostitution, but she never admitted to murder.

Martí was never convicted. Her fellow inmates hung her in the prison yard in May 1913. Rumour has it that Martí’s wealthy patrons paid for the murder to ensure that nothing about their dealings with Martí would come up at the trial. The official death certificate stated the cause of death was uterine cancer. Her death meant the investigation into her case did not go any further.

Later Reflections

Some later time authors have doubts that the matter is as straightforward as it seems at first glance. Theories have been put forward that Martí was a scapegoat to cover up the child abuse of Barcelona’s upper class and the fact that rich people were buying medicines made from children. Instead of attacking those who purchased the service, the poor who sold the children were attacked. This is certainly true, but it does not absolve Martí of what she did.

It has also been pointed out that it was pretty common for children to be sold by poor parents or kidnapped and sent abroad to work in factories or brothels. And many children were sold or stolen for adoption. Children in the slums of Barcelona at the beginning of the 20th century did not have many rights in law or practice. But again, this doesn’t absolve Martí of her guilt, and she was just a reflection of a bigger problem.

One writer theorises that Martí lost her child and kidnapped Teresita to compensate for the loss and as companionship for Angelita, the daughter of her sister-in-law, María Pujaló. It may well be that Angelita was related to Martí and stayed with her for normal reasons, but she definitely kidnapped Teresita.

I have also seen a theory that the blood found was from Martí herself, who supposedly had cervical cancer with heavy bleeding. This theory is decent as far as it goes. Nothing can be proven tough. There is also an idea that the human bones found were not bones of children but adults that someone had stolen from cemeteries. A hundred years later, nothing can be ascertained about this either.

Some have pointed out that Martí was never formally charged with murder, and a whole child’s body was never found at her home. All these theories are reasonable, but they feel like a desperate attempt to whitewash Martí or find faults in the investigation to sell books with “new findings” about the case. It’s human nature to have suspicions about cases that are so horrible that they must be exaggerated or a conspiracy. Of course, it isn’t easy now to come to any decisive conclusion about events that happened a hundred and ten years ago. Still, there is nothing to say that our predecessors did not have the same ability as us to analyse situations and draw the correct conclusions.

Marc Pastor is a police officer in Barcelona who published a novel based on the case. In an interview with VICE, he said that after he published the book, many residents of Barcelona came to him and told him that they had a grandparent who was either kidnapped by Martí or Martí tried to lure them in. This case is still alive in the minds of the descendants of the victims, and it is difficult to imagine that it was all a conspiracy to cover up the guilt of innocent citizens.

Leave a comment