Many articles and book chapters speak ill of Pope John XII. His descriptions are strong, and he is said to be one of the worst – if not the worst – pope in history. But was he that bad? Or was he, like so many men, a child of his time? Perhaps the answer is a little bit of everything. It didn’t help that he was only eighteen when he became pope, aristocratic in thoughts and deeds, and seemingly uninterested in being a servant of the Church. However, he loved the power that the papacy brought him and used it freely.

The Spirit of the Times

Before proceeding further, we must reflect on the zeitgeist of these times. In short, we are looking at a period in the history of the papacy that has been called the Saeculum Obscurum or the Dark Age of the Papacy. This term usually refers to the period that lasted from 904, when Sergius III took office, until the death of Pope John XII in 964. Previously, the Carolingian Empire of the Franks had kept a protective hand over the independence of the papacy. Still, by this time, both Rome and the papacy had fallen into the hands of powerful families in Italy who manipulated the office and competed to place their own man on the chair of St. Peter, regardless of his qualifications for the office.

The person who wrote most about this period is the bishop and historian Liutprand of Cremona. His work, Antapodosis, which in English translates as Revenge, was written to tell about the evil deeds of King Berengar II and his followers. Among them, we can count the pope in question, John XII. Liutprand’s publication was not a neutral historical work and was written to present a specific historical view.

Scholars in the 16th to 19th centuries took Liutprand’s writings as gospel, and the myth of the evil pope was born. They hated that women like Theodora, wife of Count Theophylact, ruled Rome with her husband. Their daughter Marozia became the head of the family after her parents and, for a time, became all-powerful in Rome and ruled over the papacy. This Marozia later became the mistress of one of the popes, two of her grandsons became popes (one was John XII), two great-grandsons and one great-great-grandson.

These scholars looked down on the influence of women and called their rule in Rome a pornocracy. In a pornocractic state, the government is in the hands of prostitutes and corrupt officials. Such a regime was also called hetaerocracy (rule of courtesans) and hurenregiment (rule of the harlots). Although few use such loaded terms today, historians agree that the period was a period of humiliation for the papacy, and the pope was under the influence of corrupt men and women.

Ancestry and Career

It is in this zeitgeist that Pope John XII is born. His real name was Octavian, and he was most likely born around 937 in Rome. Octavian was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. He was born in the finest district of Rome and was christened after the emperor Augustus, which tells us that the family planned great things for him.

His father was Alberic II of Spoleto, a Roman nobleman (patricius) and self-proclaimed ruler of the city of Rome. Octavian’s mother was probably Alda of Vienna, daughter of King Hugues d’Arles of Italy. This is not certain, but if true, his parents were step-siblings. Other more unclear sources suppose him to be the illegitimate son of Alberic’s mistress. If this is the case, he might have been slightly older than previously assumed.

The son was destined for great things. In 954, Alberic, barely forty at the time, fell ill and had himself moved to the tomb of St. Peter the Apostle (where St. Peter’s Church is today). In those days, the people of Rome elected the pope, not the community of cardinals. The powerful duke gathered the city’s influential people. He made them swear at the tomb of Peter the Apostle that the next time the papal throne became vacant, his son Octavianus would receive the position.

When his father died shortly afterwards, Octavian succeeded his father as ruler of the Romans. Then probably seventeen years old. When Pope Agapetus II died in November 955, Octavian was elected pope and took the name John XII.

Pope or Prince?

Octavian seems to have regarded the papacy as any other job. He issued ecclesiastical orders as John XII, but all secular orders were issued under his given name. John fulfilled his duties as pope but always felt more at home in the role of the worldly ruler. History would, however, show that he was not a particularly good or effective leader. John quickly learned he could not control the Roman aristocracy with the same dexterity as his father.

In 960, he led an army in person south against the Lombard duchies of Beneventum and Capua. The purpose was to take back territory that the Papal States had lost. The campaign did not have the expected results, and John had to negotiate for peace. At the same time, King Berengar II of Italy began attacking the lands of the Papal States in the north.

To defend against Berengar and to secure his position among the nobles of Rome, John sought the support of Duke Otto I of Saxony and the King of the Germans. Otto was a powerful king who was later named Otto the Great. Otto invaded Italy and reached Rome in January 962. Berengar retreated into his lands and fortified himself.

In Rome, Otto swore an oath to do everything in his power to defend the Papal State’s independence and give back to the papacy all the lands he would recover from Berengar. In return, John crowned Otto as emperor and inadvertently revived the Holy Roman Empire. The resurrected empire lasted until 1805, when Napoleon dissolved it. The pope and the nobles of Rome swore an oath on the tomb of Peter the Apostle to be faithful to the emperor and not to help Berengar II and his son Adalbert in any way. The emperor retained his veto right in papal elections and inserted clauses in the agreement that limited the secular power of the pope.

To begin with, everything went smoothly between Otto and John. But it soon became apparent that they were very different personalities. As strange as it sounds, the pope was just a teenager primarily interested in sex, cards, hunting and drinking. Otto, however, was thirty years older and a serious political leader. He was widely praised as the epitome of piety and chivalry. Something that we could not say about the young pope. Otto, on the other hand, was on a mission. He devoted his life to defeating his enemies and uniting Germany into one state. His ultimate goal was to restore Charlemagne’s empire. So, of course, he jumped at the chance when John promised a coronation for military protection.

Otto was only two weeks in Rome. Despite their brief association, the relationship between the pope and emperor quickly soured. Otto, who was much older and had become emperor of the Romans, believed he was in a position to lecture the young pope. He didn’t think much of the immoral lifestyle and the political ambitions of a man who was supposed to be a man of the Church. Pope John was consequently pleased when Otto left Rome in March 962 to fight Berengar.

John disregarded everything Otto had advised him and immediately resumed his visits to his mistresses, his betting and his custom of sleeping with female pilgrims who visited Rome. In his military camp, Otto soon received news from his messengers that the Lateran Palace had become a “whorehouse”. At first, Otto was relaxed about the young man’s moral transgressions. Then, he began hearing stories that Pope John had started befriending Adalbert, Berengar’s son.

John was beginning to fear Otto. Otto was successful on the battlefield and became a more powerful ruler daily. Therefore, soon after Otto saved Pope John, the latter began to plot against his rescuer. John sent envoys to Byzantium and Hungary and proposed their alliance with the Papal State and Berengar against Otto.

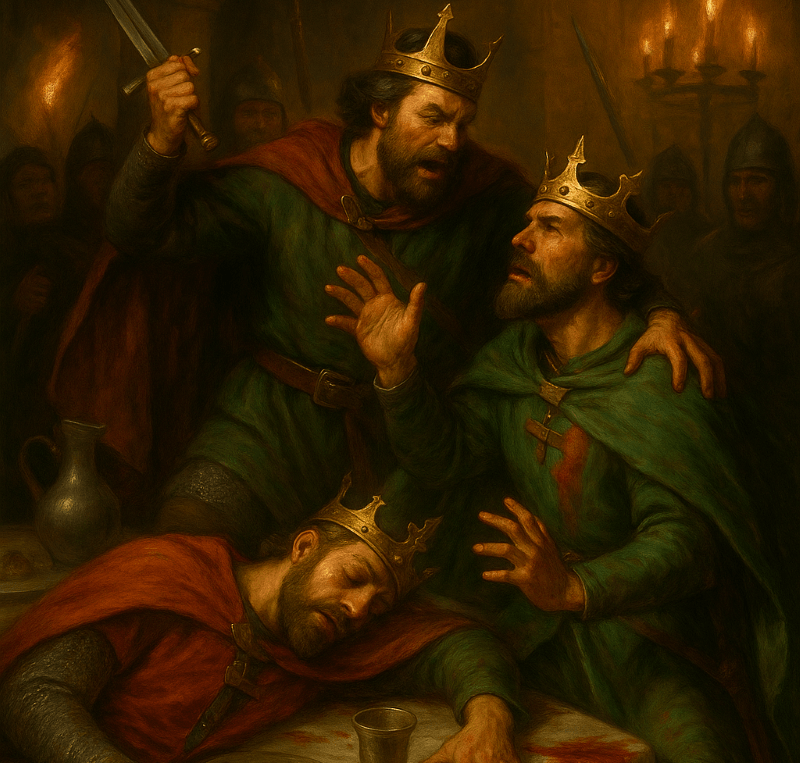

Like most things Pope John planned, the conspiracy failed. Otto became furious when he learned that John was planning on putting Adalbert on the throne and besieged Rome in 963. John quickly realised he could not fend off Otto, took the papal treasury, a vast amount of alcohol, and all the prostitutes he could and fled.

Otto called a church synod, demanding Pope John attend and defend his actions. John refused to participate and threatened to excommunicate anyone who tried to depose him. These threats did not stop the emperor and the synod, which elected Leo VIII as pope in early December 963. However, Otto had more important things to do than hang out in Rome and deal with the affairs of the Church and left the city as early as January 964.

When Otto left the city, John returned with a group of his supporters and put Leo VIII to flight. John convened another synod that declared his removal from office against church law. He then set out to revenge himself on those who spoke against him at Otto’s synod, and either had their tongues cut out, their fingers cut off, or their noses sawed off.

John sent delegates to reconcile with Otto, but in May 964, before they succeeded, John died. Sources do not entirely agree on how he died. One source states John got a heart attack while having sex with a married woman. Another source declares he died of internal bleeding after being beaten by the woman’s husband, who came upon them in bed. He was only twenty-seven years old.

The Corruption

John always behaved more like a corrupt worldly leader than the head of a church. He was described as a rough and immoral man. His life was such that the Lateran Palace was referred to as a whorehouse, and the corruption in Rome became the cause of public outrage.

Many used his lecherous lifestyle against him. Not only because he was a pope but also for political purposes. Liutprand of Cremona, loyal to Emperor Otto, wrote in detail about the accusations against him at the Synod of Rome in 963. The charges varied. One cardinal testified that John had served in a mass without consuming the sacrament. Bishop Peter of Narni testified that he saw John ordain deacons in a stable. Other clerics stated he got paid for making men bishops. He even made a ten-year-old boy a bishop in Todi for a handsome payment.

Clerics claimed they had proof that he had sex with known widows, his father’s mistress and with his aunt. They also claimed that he kept prostitutes in his papal residence. Witnesses came forward who said he had gone hunting in public. He is also said to have blinded his confessor, who died shortly afterwards. He was accused of castrating and then killing Cardinal John. Pope John is said to have set fire to houses and ridden through the streets of Rome armed with swords and armour. Witnesses also said that he toasted the devil and invoked Jupiter, Venus and other demons while playing dice. They also stated that he did not partake in lauds and never crossed himself.

We must be careful not to believe everything that Liutprand wrote down. Many witnesses surely gave their testimony at the synod under political pressure. But other contemporaries told a similar story. They may not have told such extreme tales. Still, they all questioned the morality and suitability of this militant nobleman to lead the Church.

In later times, some historians denounced him as a murderer, a robber and a morally depraved sex addict, but others were more lenient. Yet all agree that he was more of a nobleman than a clergyman and was not greatly interested in ecclesiastical duties.

We must remember that he rose to great power before fully matured and did not always make good decisions. But what teenager with outrageous powers would tolerate such pressure? Strong nerves and good support are needed. Like other young nobles, he was primarily interested in girls, alcohol and betting. We know he was part of a gang of corrupt nobles, behaved like them and got away with many things because of his lineage and status. But no matter how much we try to defend him and put his behaviour in a historical context, everyone agrees that he was anything but a good pope. Whether he was the monster some have claimed is another question.

Leave a comment