It is not unreasonable to assume that few people know of the Kingdom of Aksum. Despite being one of the greatest empires of Late Antiquity, we have heard little about it. The reason can be attributed both to the fact that the history of Africa has perhaps not reached our view of history and that the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia was completely closed in among its Islamic neighbours and completely disappeared from the eyes of Europeans for many centuries. It is not until the second half of the 20th century that the state’s history begins to reach our ears.

About Aksum

Aksum was a great naval and trading power between 100 and 940 in what is now Eritrea and the northern part of Ethiopia (now the Tigray region). When the kingdom was at its most powerful (1st-7th century), it was one of the four great powers of its time, along with Persia, the Roman Empire and China. It covered an enormous area at its height, totalling 1.25 million square kilometres, which today is northern Ethiopia, Eritrea, northern Sudan, southern Egypt, Djibouti, western Yemen, and southern Saudi Arabia.

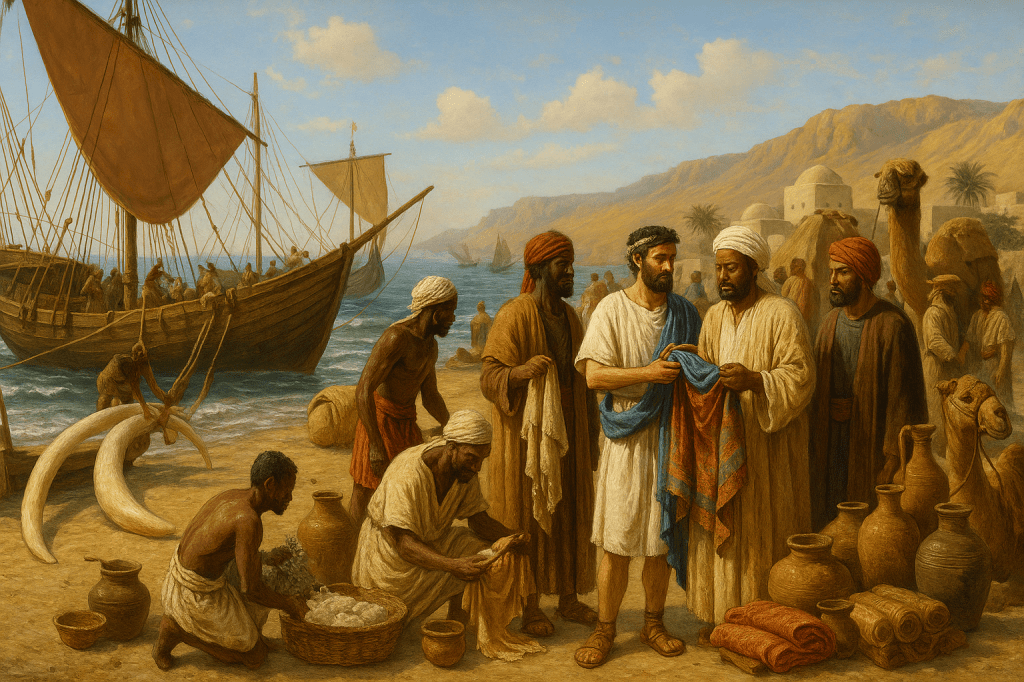

The kingdom had enormous influence as a trading power as it straddled the borders of Africa, Arabia and the Greco-Roman world. People from Egypt, Arabia, Europe and Asia visited the land and even settled there. Coins minted in Aksum have been found in both China and India, as the state was a powerful intermediary in trade between the Roman Empire and India. The kingdom’s influence spread far and wide, but other cultures had an equally strong influence on the kingdom, and Greek became one of the main languages of the realm. From the empire’s largest port city, Adulis, Aksum’s merchant fleet controlled trade and commerce in the Red Sea, and they were also a powerful player in the overland trade in Northeast Africa.

Origin and History

Despite being indisputably one of the greatest powers in the world at the time, little is known about it. The Aksumites had a script, and no doubt they wrote a lot, but little of it has been found, and only fragmentary stories exist about the kingdom and not enough to make the kingdom alive in history as can be done with the Roman Empire or Greece.

The Italian orientalist Carlo Conti Rossini wrote much about Ethiopia and was a pioneer in that field. He did his research at the beginning of the 20th century when Italians, led by Mussolini, were very interested in Ethiopia. The interest of the Italians ended with them invading the country in 1935.

Rossini’s theory, which historians accepted for a long time, is that Aksum was founded by the Sabaeans, who were ancient people who spoke a Semitic language. These Sabaeans lived in what is now Yemen and established the kingdom of Sheba. We would probably have heard little of that fine kingdom if it weren’t for the Bible story of the Queen of Sheba. According to Rossini, the Sabaeans sailed across the Red Sea to Africa and founded the kingdom of Aksum. Most scholars agree that the state was created purely among the local people in Africa, although it is somewhat unclear how it happened.

Most people today agree that the kingdom came into being after the end of the D’mt kingdom. That kingdom was located in Tigray, a plateau in northern Ethiopia. The state had developed strong agriculture and some trade with countries such as Egypt. After the fall of D’mt, the region split into many smaller kingdoms. These kingdoms then slowly merged over a long period into what is today known as Aksum in the 1st century AD.

The first written mention of Aksum is in a publication that we could call Navigational Guide to the Erythraean Sea (Periplus Maris Erythraei). Periplus is a publication that lists ports and landmarks along the sea and includes longitude measurements to help captains. The Periplus Maris Erythraei describes the shipping route and trade possibilities from Rome to Egypt and along the coast of the Red Sea and to other ports in the Horn of Africa, the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. According to this publication, Aksum had become an essential link in the trade route between Rome and India as early as the first century of the kingdom.

The state became more powerful every year, and in the 3rd century, we can read in sources about many successful military expeditions. It was in the 6th century that the Aksumites began to attack Yemen and held the reins of government there for a while. The warfare there ended badly for Aksum after the Yemenis got help from the Persian Empire. It is widely believed that this war in Yemen was the beginning of the end for Aksum as a great power, as it cost considerable money and manpower. The state remained a powerful kingdom and trading power, but its dreams of being a military power were over.

Culture and Religion

The culture of Aksum is remarkable in many ways. The Aksumites developed their own alphabet and coins to facilitate trade in their region, the first people south of the Sahara. The Aksumite alphabet, called Ge’ez, is remarkable and is the only alphabet developed by native Africans. The Kingdom of Aksum was, in fact, Africa’s contemporary counterpart to the Greek and Roman civilizations we know so well. Aksum is a fascinating example of a sub-Saharan culture that flourished when the great Mediterranean empires were coming to an end.

The kingdom was a link between the two worlds of the Mediterranean and Asia and shows us the extent of international trade at this time. The Aksumite culture is not least remarkable for being a civilization that disappeared from our sight for hundreds of years even though it had international importance and its own alphabet, robust manufacturing of coins, importance in African history and was part of the Christian world. We can easily argue that their culture was just as advanced at that time as the European powers.

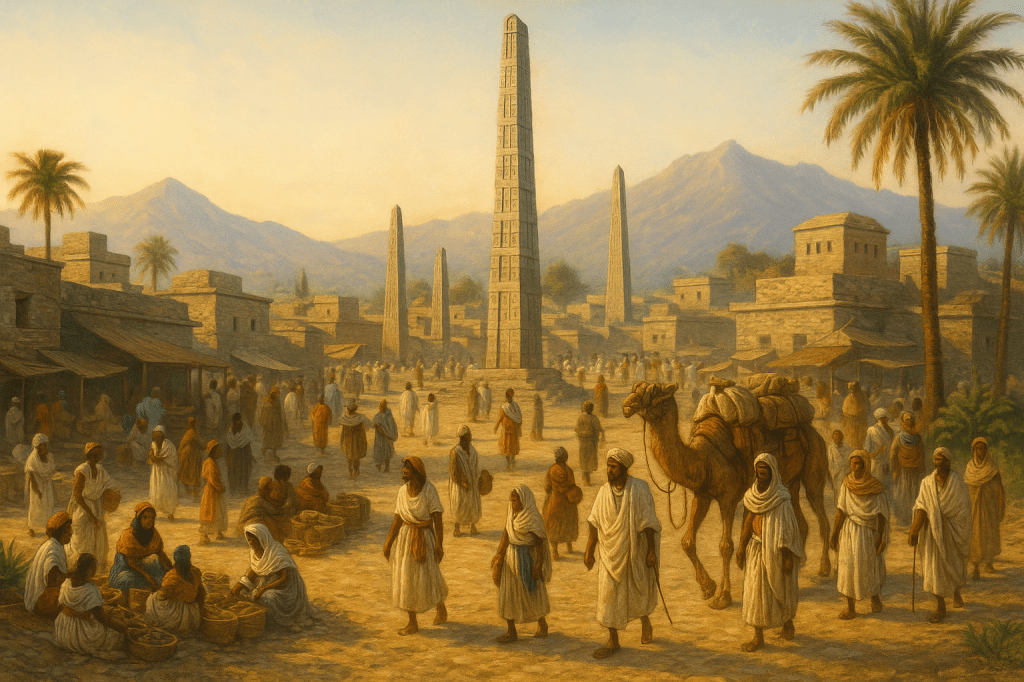

The Kingdom of Aksum is known for building substantial spiked columns (obelisks) to adorn the tombs of kings and nobles. The most famous is the so-called Obelisk of Aksum, a seventeen-hundred-year-old structure that weighs one hundred and sixty tons and is twenty-four meters high. Sometime in the past, the obelisk fell, most likely in an earthquake. It lay half buried in the ground until the Italians found it during their invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and took it as plunder to Rome. The Italians returned the obelisk in 2005, and now it stands in the empire’s ancient capital, Aksum, in the middle of the war-torn Tigray region.

Aksumite society was highly stratified, with the king at the top, followed by his nobles, and then the ordinary people below. Very little of their writing describes the kingdom’s social structure. We can assume that, as in other similar societies, priests were important and probably merchants also because of their wealth. Farmers, workers and craftsmen probably made up the poorest tier. Little is known about the role of women or Aksumite family life.

The king was often called the king of kings, which tells us that he probably ruled over lesser kings who, in turn, ruled smaller units, provinces and tribes within the larger kingdom. Archaeological research has given us evidence that there were at least ten to twelve urban centres in the Kingdom of Aksum. This research suggests that it was an urban society mixed with an agricultural society.

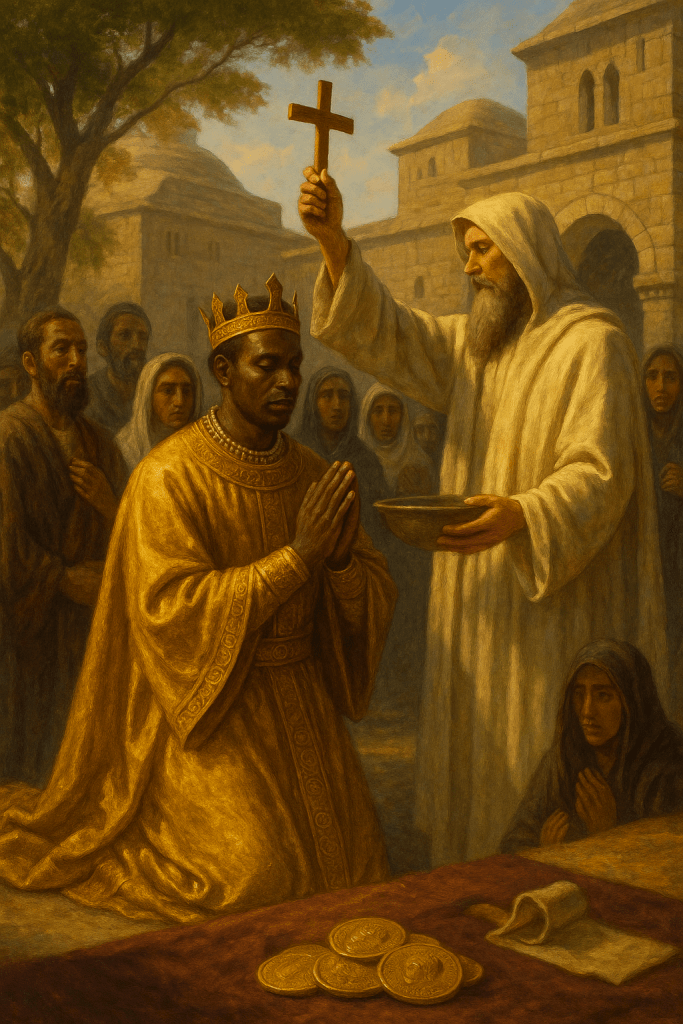

The Aksumites were polytheistic until they converted to Christianity in 325 or 328 during the reign of King Ezana. Ezana and other inhabitants of the country were converted to Christianity by Saint Frumentios, a freed Phoenician slave who founded the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Aksum was the first state in history to put a cross symbol on its coins. Today, about 60% of Ethiopia’s population is still Christian.

Despite being a Christian state, Judaism was also significant within the state. The Jews within Aksum were called “Black Jews” and wrote their religious writings in the Aksumite script rather than in Hebrew. They still followed the doctrines as outlined in the Hebrew scriptures. However, many religious scholars do not consider them Jews but proto-Christian Semitic people who share a common heritage with Judaism. Judaism’s ties to the territory were finally severed between 1985 and 1991 when almost all Ethiopian Jews were deported to Israel.

Finally, we cannot discuss the history and culture of Aksum without mentioning the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon. According to the legend, Sheba, Queen of Aksum, went to Jerusalem and met King Solomon of Israel. Their meetings ended with her becoming pregnant, and their son Menelik I is considered the founder of the Solomonic dynasty, to which the rulers of Ethiopia traced their lineage until the 1970s.

Another legend worth mentioning is that Aksum was the home of the Ark of the Covenant from the Bible, which holds the tablets with the Ten Commandments. The Ark is supposed to be kept in the city of Aksum, specifically in the Church of Saint Mary of Zion, where a single monk watches over it. Legend states that King Menelik I seized the Ark from Jerusalem and took it to Aksum. Similar stories place the Ark all around the world, but the story of it being in Aksum is popular.

Economy and the Basis of Prosperity

Aksum was an essential intermediary between India and the Mediterranean countries (mainly the Roman Empire and later the Byzantine Empire). The kingdom exported ivory, tortoise shells, gold, precious stones, and imported silk and spices. Aksum’s access to the Red Sea and the Upper Nile meant that their large fleet of ships profited greatly from trade between different European, African, Arab and Indian states.

Aksum’s economy was primarily based on agriculture and the export of agricultural products. The soil in Aksum was considerably more fertile during their empire than it is today, which made it possible for them to grow a lot of wheat and barley, which they then sold to many parts of the world. The people of Aksum also raised cattle, sheep and camels. Aksum also made a lot of money from hunting wild animals and selling ivory and rhinoceros horns.

In addition, their land was rich in metals, and they exported a considerable amount of gold and iron. The export of these metals gave a good return. In addition, there was a lot of salt in Aksum, which they could export with great profit. No wonder the state prospered.

But why did Aksum suddenly become such a significant trading power? The simple answer is favourable circumstances. Aksum benefited from the revolution that took place during this time. The sea trade route that connected the Roman Empire to India changed entirely in the 1st century. Previously, trade had involved coastal shipping and overland travel, with many stops at various ports and cities. The Red Sea was secondary to trade with the Persian Gulf and land connections with the Near East.

In the 1st century, however, traders began travelling from Egypt to India, using the Red Sea and monsoon winds to cross the Arabian Sea directly to southern India. This change resulted in a significant increase in Roman demand for goods from India. Larger ships began to sail down the Red Sea from Roman Egypt to the Arabian Sea and India. On this route, Aksum was ideally located, and the Aksumite port city of Adulis soon became the main port for the export of African goods at the expense of the Kingdom of Kush, which had previously supplied the Egyptians and Romans with African goods along the Nile.

Decline and the End

The empire’s period of decline is called the Dark Ages of Aksum. It isn’t easy to point to one specific cause for the kingdom’s end. Scholars point to several factors: geopolitical changes, the unsuccessful war in Yemen (as mentioned earlier), the rise of Islam, and climate change. We should remember that these changes took place over a very long period, and Aksum’s decline lasted for about three hundred years.

First, let’s look at the geopolitical changes and progress of Islam. Aksum had its second golden age in the 6th century, but as it got nearer the 7th century, the state began to decline, and by the early 7th century, the state had reached the point where it stopped producing its currency. Aksum’s empire was under pressure when the Persian Empire began to spread across the Red Sea region. The Persians pushed Aksum out of the southern Arabian Peninsula and pressured their trade empire around the Red Sea.

The Christian state became further isolated as Islamic Arab states began encroaching on them in the 7th and 8th centuries. Their isolation caused their trading empire to shrink and suffer permanent damage. Adulis, the largest port city of Aksum on the Red Sea, was destroyed in attacks during this time. The people of Aksum were forced to retreat further inland because they were safer there. This movement eventually led to the abandonment of the capital that the state was named after.

The state was still powerful if contemporary Arab sources are anything to go by. However, it had lost control of most of its coastal areas and no longer controlled the highways of the time: the Red Sea tributaries. And although the state lost its territories in the north, It added territories to the south of the state. A new capital was established, but it is unknown where it was or even what it was called.

According to the oral history told from generation to generation, the Jewish queen Yodit or Judith finally conquered Aksum in 960. That year is most often mentioned as the end of the kingdom. Yodit is said to have burned Christian churches in the kingdom and destroyed its literary works. Although archaeological remains show that churches were burned and the country was verifiably invaded during this time, scholars doubt the veracity of these stories. Another legend states that a pagan queen named Bani al-Hamwiyah defeated Aksum. The only thing historians are pretty sure about is that a female leader seized power and ruled until 1003. After that, many other states took over the territory in turn, which is too long an account to go into here. But we should remember that even though the Aksumite kingdom itself had ended, the Aksumite culture was still prevalent in the region for centuries to come.

As mentioned earlier, there is strong evidence that climate change caused or contributed to the fall of Aksum. At the height of Aksum, the rainy season was unusually long, about six to seven months instead of the usual three months. This meant that these suitable conditions doubled the growing season, and it was possible to harvest twice a year. As the rainy season began to shorten, it became challenging to grow enough for the population and export. The inhabitants of the country still continued to try to cultivate the same amount as before, which caused over-cultivation of the fertile land. Right around 700, the soil had become less productive, and the state’s agriculture was in decline. In addition, historians believe that due to the government’s extensive construction projects, logging was out of control, causing extensive vegetation destruction.

Likely, changes in vegetation, over-cultivation of land and pressure from Islamic neighbours triggered a development that ultimately brought down the Aksum Empire.

Leave a comment