In the past, the parents usually decided who the family’s children married, especially in the upper levels of society. The Renaissance in Italy in the 17th century was no exception. The parties who were to be married had little say in the matter. Marriage was a social and economic issue for the entire family.

The bride-to-be had least of all a vote in these matters. She was often seen as a product the family could sell in marriage for their benefit. Women and men, therefore, often married someone they did not know and did not know if they would get along. If the relationship was terrible, there was little they could do because there was no possibility of divorce. Only death could end a marriage.

Most of the time, the marriage was a success and mutual respect and even love developed over time. But sometimes, the unions were terrible. Either because the husband had the power and could inflict mental and physical violence on the woman without expecting punishment or simply because the spouses did not get along. The only way to get out of a bad marriage was to become a widow or widower. However, some women did not want to wait years or decades for it to happen. Giulia Tofana was a woman who wanted to help other women to become widows immediately.

Giulia

Giulia Tofana was namely one of the most prolific mass murderers in history. Still, for some reason, she is rarely on any list of the greatest serial killers. This might be the case because she didn’t kill with her hand. Her profession was to prepare poison for women who wanted to kill their husbands. Giulia caused hundreds of people to die prematurely in a twenty-year career.

Very little is known about Guilia Tofana’s life. There is no picture of her, but sources described her as “beautiful”. She became a widow early. We don’t know how it came about, but it’s not unlikely that she poisoned her husband, given her achievements later in her career.

We know that she was born around 1620 in Palermo, Sicily, the daughter of Thofania d’Adamo, who was executed in Palermo on July 12, 1633, for killing her husband. Sources say that Giulia spent a lot of time with apothecaries in her youth (perhaps as an apprentice or a pharmacy worker) and learned to prepare medicines and remedies. Eventually, she developed her own poison, later called Aqua Tofana after her.

We know that Giulia sold cosmetics in Palermo and elsewhere in southern Italy. Along with the cosmetics, she sold her poison to women who wanted out of their marriage. We know nothing about why these women wanted to get rid of their husbands. If it was abuse, the difference in personalities or something else.

Some who have written about Giulia discuss her compassion for women in abusive relationships. There is nothing in the sources to prove it, but it is not an unlikely reason. She seems to have sold her poison only to married women who wanted to get rid of their husbands. Her reputation slowly spread among women contemplating this. Her clients came to her after referrals from widows who succeeded in their mission.

The Family Poison – Aqua Tofana

Dabbling in poison was a family business for the Tofana women. As mentioned before, Giulia’s mother killed her husband. There is speculation that Giulia did not invent the poison Aqua Tofana herself, as is commonly believed, but that her mother used it on her husband and then passed the recipe on to her daughter. But of course, these are just guesses.

We know that Giulia’s daughter, Girolama Spera, was involved in the family business. The daughter, also known as “Astrologa della Lungara” was executed as a poisoner with her mother. We also know that the family moved from Palermo after Giulia became a widow, first to Naples and then to Rome, where authorities eventually discovered the family business.

The family poison, Aqua Tofana, is an interesting blend. It contains Arsenic, lead, and atropa belladonna, commonly known as belladonna or deadly nightshade. We do not know in what proportions the poison was mixed. The poison was suitable for women who wanted to get rid of their husbands because it was difficult to see what was wrong with the victim. The poisoning came on slowly and mainly resembled a common illness initially, which then progressed into a more severe illness until the patient died to all appearances from natural causes.

It only took four drops to kill a grown man. It was best to administer the poison drop by drop over several days or weeks to avoid suspicion. The poison was completely tasteless, odourless and colourless, making it perfect for mixing into drinks or soups. The first dose produced a regular fever. After the third dose, the victim had become severely ill, had diarrhoea, vomiting, dehydration, and felt a burning sensation in the gastrointestinal tract. A fourth dose killed the victim. In the 17th century, such development of disease symptoms was considered normal, as medical science was not as developed as it was later, and toxicology screening was available.

The poison had the added benefit that the husband fell ill slowly and, therefore, had enough time to complete his affairs. Even finalising a will where the beloved widow would be well cared for. And if someone began to whisper that the wife had poisoned the man, she could request an autopsy, where it was certain that the doctor would find nothing abnormal.

Good Packaging is Important

Giulia’s genius was how she disguised the poison. To begin with, she concealed the poison as a cosmetic powder for women. Women could therefore keep it among their perfumes and cosmetics without their husbands looking at it further.

Later she got an even better idea and started selling the poison in small bottles with a picture of Saint Nicholas of Bari (the one who later became Santa Claus). The bottle said it was “Oil of Saint Nicholas of Bari”. This oil, called “manna”, was a healing oil that was said to have leaked from the tomb of Saint Nicholas and was sold to pilgrims.

The genius of this packaging was that the husband did not care if the wife had a bottle of miracle oil at home. They were even willing to have a small portion of it themselves. Later, when the scheme was discovered, Giulia’s customers had a good excuse. They could claim that they thought this was real holy oil and that their husband’s death was an accident.

The Fateful Soup

Giulia’s enterprise could have continued for a long time if not for the incident with the soup. A woman bought Aqua Tofana from Giulia and put it in her husband’s soup. When the man was about to eat the soup, the woman felt guilty and stopped her husband. The man became suspicious of her strange behaviour and forced the truth out of his wife. He then brought her to the authorities in Rome, where the woman confessed and identified Giulia as the seller of the poison.

Giulia had her allies and was helped to avoid the long arm of the law. She managed to escape to a church, where she was granted asylum. But when a rumour spread that she had poisoned the city’s water supply, the police disregarded the church asylum, stormed the building, and seized Guilia.

Giulia was tortured until she confessed to having caused the death of over six hundred people when she lived in Rome between 1633 and 1651. Not to mention the poison she sold in Naples and Palermo. It is impossible to guess the number of victims as most of her clients got away with their crimes. It could be lower or even higher. And as always, we must take any confession under torture with a grain of salt. All we know for sure is that the poison was very popular and widespread.

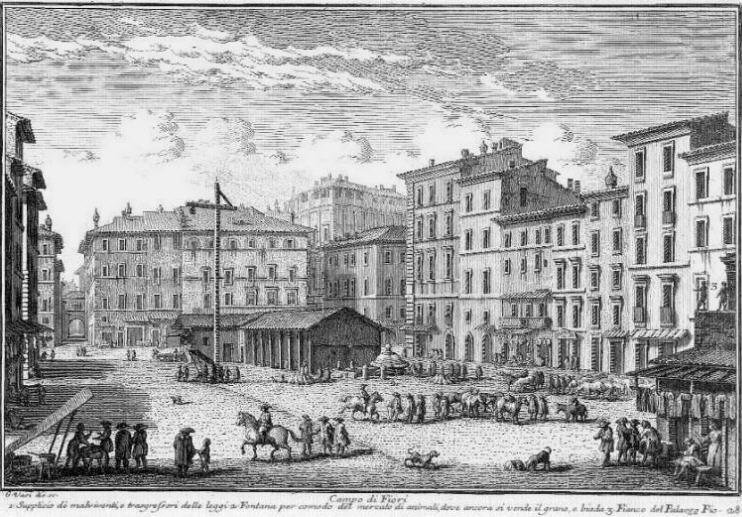

Giulia was executed along with her daughter and three assistants in July 1651 in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori square. Under torture, she gave the names of over forty clients who were later executed or imprisoned. Lower-class women were put to death, while upper-class women were imprisoned or escaped punishment. It is curious to know how the relationship was between a couple where the woman had intended to poison the man but escaped punishment and was sent back home.

Despite Giulia Tofana’s death, husbands were not safe with their life, and women continued to poison them, either with Aqua Tofana or other means. After all, the poison was untraceable and remained popular.

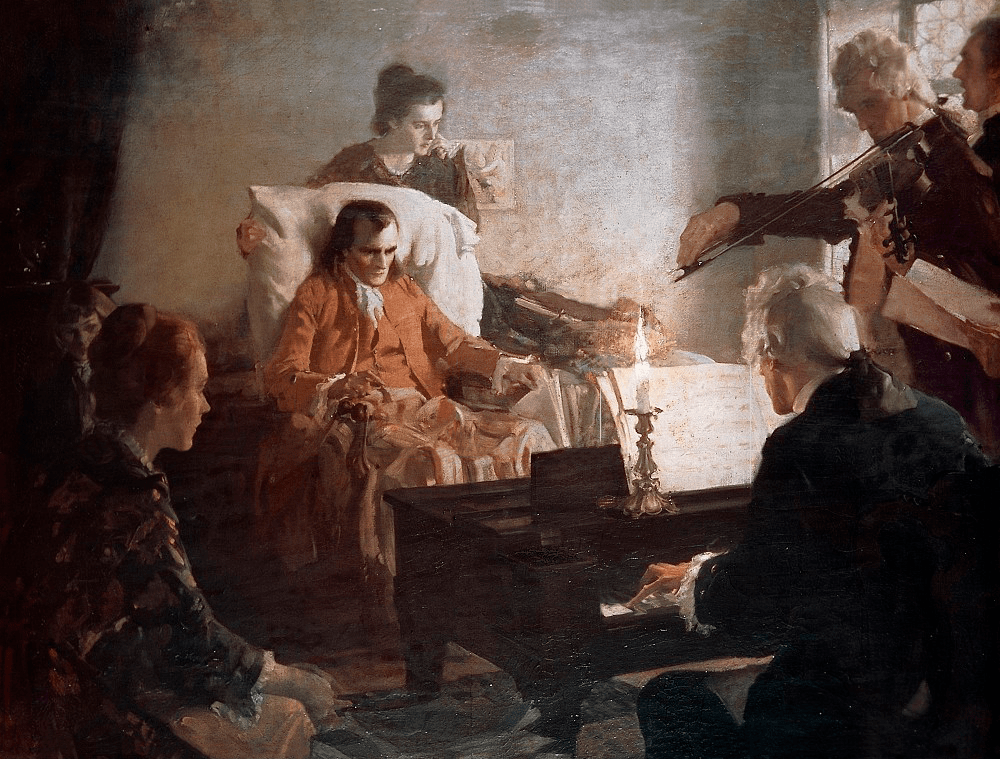

Mozart

One legend that always accompanies the story of Giulia Tofana is the story of the poisoning of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. In this legend, Mozart is supposed to have died from Aqua Tofana in 1791. However, there is nothing to support this story – even though it was Mozart who started the rumour. When Mozart was dying, he declared that he had a short time left, and he was sure that Aqua Tofana had poisoned him. But nothing was proven or disproved at the time.

A study of Die Zauberflöte, an opera that Mozart was working on near the end of his life, revealed high Arsenic levels in the manuscript. Arsenic is one of Aqua Tofana’s ingredients, which makes this study interesting. However, Arsenic can be found in many objects and foods in nature. People used it for various purposes, such as medicine and paint. Therefore Arsenic could come from anywhere. Consequently, nothing directly connects Aqua Tofana to the manuscript and Mozart’s death.

This legend and Mozart’s thoughts still show that Giulia’s poison was still on people’s minds a hundred years after her death. So it must have still been in some use.

One guilt-ridden wife eventually ruined Giulia Tofana’s business. If that hadn’t happened, she might have been able to go on for the rest of her life, and no one would be any wiser. It’s a question of how many poisoners and killers have gotten away with the same thing, and worse, without us knowing their story.

Leave a comment