Once there was a prince in Wallachia (now part of Romania) named Vlad III Drăculea, often called Vlad the Impaler (Vlad Țepeș). He is known in his homeland as one of Wallachia’s most remarkable rulers and a national hero in Romania. If it weren’t for the fact that author Bram Stoker borrowed his name for his novel Dracula, he would surely just be a Romanian prince that none of us would ever think of.

But since the story of Dracula has been the motivation for movies, TV shows, plays, novels and comics for decades, we naturally have an interest in the real Dracula. Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula only makes tentative references to the 15th-century prince. Who was the real Dracula?

Childhood

Vlad was born in Sighişoara in 1431, then in the Kingdom of Hungary but is today in Romania. Vlad was the son of Vlad II Dracul, prince of Wallachia. Vlad II was educated in Nuremberg at the court of Sigismund of Luxembourg, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1431 he was initiated into the “Order of the Dragon”, which had been founded in 1387 as both a military order and a religious brotherhood to protect Christian lands from the aggression of the Ottoman Empire in Eastern Europe. Somehow the name of the order stuck with Vlad II, and his surname became Dragon – Dracul in Romanian. Vlad and his brothers (Vlad was the next oldest of the four) were given the surname Dracula which means “son of Dracul”.

Pope Pius II’s legate Niccolò Modrussa is the only person who left a written description of Vlad after meeting him in Buda. According to him, Vlad was not very tall but stocky and muscular with a stern and menacing look. A large and aquiline nose, bulging nostrils and a thin and reddish face where very long eyelashes framed large and wide-open green eyes. Big and thick eyebrows made his glance menacing. The face was shaved except for the moustache. The swollen temples increased the size of the head. A thick neck joined the head from which black curly locks fell over his broad shoulders. No small description of the man!

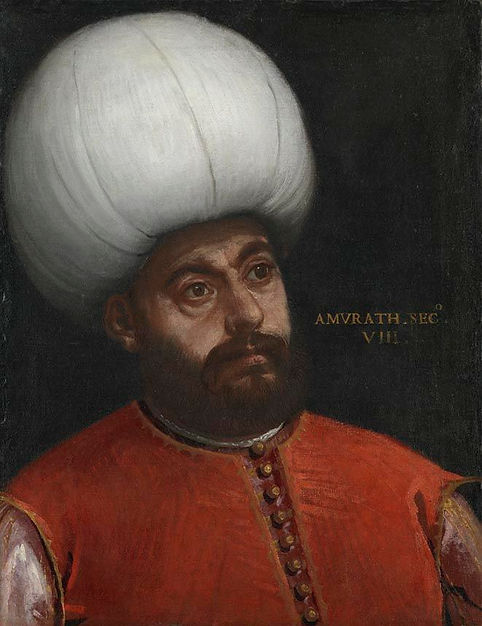

Vlad III was well acquainted with the Ottoman Empire, as he and his brother, Radu the Handsome, were taken hostage by them in 1443 after their father’s failed campaign against them. The prince, Vlad II, was eventually released, but Sultan Murad II kept the sons at his court to guarantee the Wallachian prince’s loyalty.

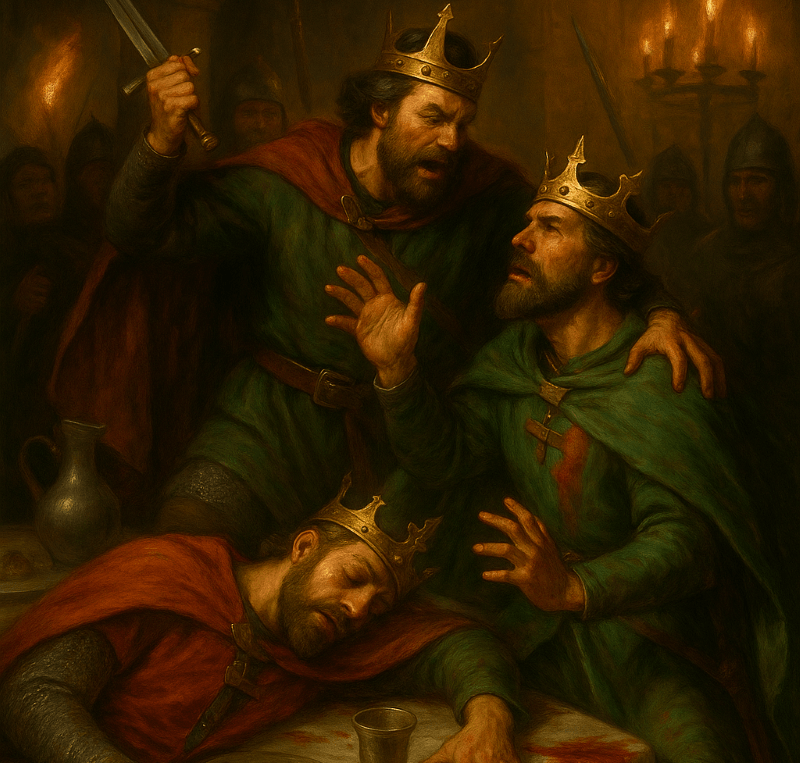

In the winter of 1447, King János Hunyadi of Hungary invaded Wallachia and murdered Vlad II and his eldest son Mircea. Mircea was blinded with hot iron bars and buried alive in Târgovişte. King Hunyadi gave the principality to a new family (the Danești dynasty) and its head, Vladislav II, became prince.

The Prince Who Loved to Impale

The brothers were held captive by the Ottoman Empire until 1448. Vlad III was then released, but his brother remained and became an ally of the Ottoman Sultan. Vlad III waged war in his homeland against the local nobility and came to power in late 1448 with the help of the Turkish Sultan when Prince Vladislav II was away on a campaign. The victory was short-lived as Vlad fled after only two months on the throne when Vladislav II returned. Vlad first settled in Edine in the Ottoman Empire but then went to Moldavia, where he was exiled until 1451.

From there, Vlad returned to Transylvania and settled at the court of János Hunyadi, the same king who deposed his father. King Hunyadi became Vlad’s political mentor. At this time, there was significant political turmoil in Eastern Europe, and Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. In 1456 Vlad returned to power in Wallachia. We don’t know how it happened, but his second reign as prince became his longest and most important.

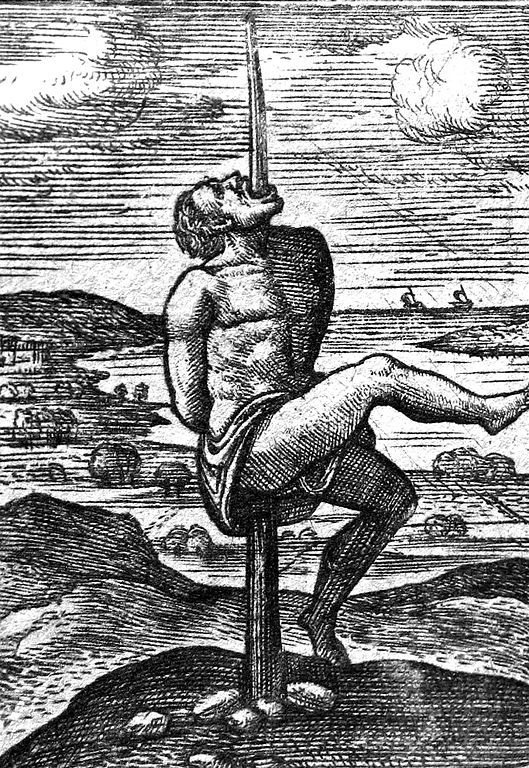

It was during this period that he gained his reputation for cruelty that was to follow him. He became known for impaling his enemies. During impaling, a pointed stake is driven into the ground, and the person is placed on top of it so that the stake punches up through the butt and out the mouth. The victim dangles like this until he dies.

For this method of execution, Vlad was nicknamed Vlad the Impaler or Vlad Țepeș in Romanian. He used this method on both domestic and foreign enemies, and famously when he retreated in a battle against the Turks in 1462, he left a field of thousands of impaled victims. The idea was to deter the Turks from pursuing him.

There are many stories of Vlad’s cruelty. After Transylvanian merchants ignored duties on imported Transylvanian goods, he intervened and impaled the merchants. Then there is the famous tale of when Vlad had part of the city of Brasov burned, impaled the inhabitants, men, women and children, and then sat down among the slaughtered and ate breakfast to his heart’s content. He is also said to have boiled people alive in a large pot.

Antonio Bonfini wrote in Historia Pannonica around 1495 that when Turkish envoys came to visit Vlad, they refused to take off their turbans because it was against their ancient customs. Vlad decided to enshrine this custom by nailing the turbans to the emissaries’ heads so they could not take them off. Stories like these must be approached with a grain of salt, though, as the stories are exaggerated or made up by his enemies.

War with the Ottoman Empire

During his second reign, his relationship with the Ottoman Empire soured significantly. He refused to pay tariffs to the Ottoman Empire and send young men to serve in the sultan’s slave army (the Janissaries). He even refused to appear before the sultan’s court in Constantinople when he was summoned there and impaled the Turkish envoys.

By 1461, the Turks feared that Vlad III would ally with Hungary by marrying a Hungarian princess. The Turks demanded that he pay tribute to them and cut off all relations with Hungary. Vlad responded by capturing the Turks’ fortresses along the Danube and plundering their territory in northern Bulgaria.

Sultan Mehmed II responded by sending his army to Wallachia in April 1462 to capture the province or replace the prince. It is difficult to find an exact timeline of how the war was fought, but we know that Vlad used guerilla warfare. He attacked the Turkish camp at night and avoided fighting them in the open. He also left scorched earth on his retreat so that the Turks could not use the gifts of the land.

With the help of Vlad’s handsome younger brother Radu and other Wallachia nobles, the Turks eventually managed to drive Vlad to Transylvania, where he sought the help of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. Corvinus, however, arrested him.

According to the chronicler Antonius Bonfinius, living at Corvinus’ court, it was unclear why Corvinus decided to arrest him. One thing is certain, the Germanic Saxons of Transylvania helped in Vlad’s downfall and capture and then did their part to tarnish his reputation and create the ideas we still have about him. The Turks made his brother Radu the prince of Wallachia, as he was a close ally of theirs.

The Hungarians held Vlad III until 1474. In 1475 he returned to Wallachia and fought the Turks in Serbia and Moldavia. In the same year, his brother Radu died. So at the end of 1476, Vlad III took over the reins of Wallachia for the third time. But this time, he reigned very briefly and died in battle near Bucharest in late December 1476 or January 1477.

The legend says that he was beheaded and his head sent to the Turkish Sultan. The rest of his remains were said to be in St. Mary’s Church in Snagov Monastery north of Bucharest. However, when his grave was excavated in 1933 during an archaeological dig, no coffin with human remains was found, only horse bones.

Legacy

Vlad III has been considered a national hero in Romania (mainly since the 19th century) due to his fight against the Ottoman Empire. Still, outside of Romania, his reputation has not been as good. Stories and legends about him outside his homeland have been terrifying and downright diabolical.

When the printing age started, illustrated German books about his brutality were among the first bestsellers in the German-speaking parts of Europe. These books contributed to the dissemination of a specific image of Vlad III that continued in other European literature and eventually became world famous through Bram Stoker’s novel.

It has often been assumed that Stoker based the title character of his novel on Vlad, but there is nothing to prove it other than that he borrowed the name. Stoker’s notes mention the name Dracula as a 15th-century count but say nothing more. The fact remains that the main character in Stoker’s book was Count Wampyr until the very last draft when he borrowed the name from the prince and various facts about Wallachia. Stoker was also the first to connect vampire legends with Dracula. Despite the Prince’s long history of cruelty, he had never been accused of being a vampire before Stoker.

Leave a comment