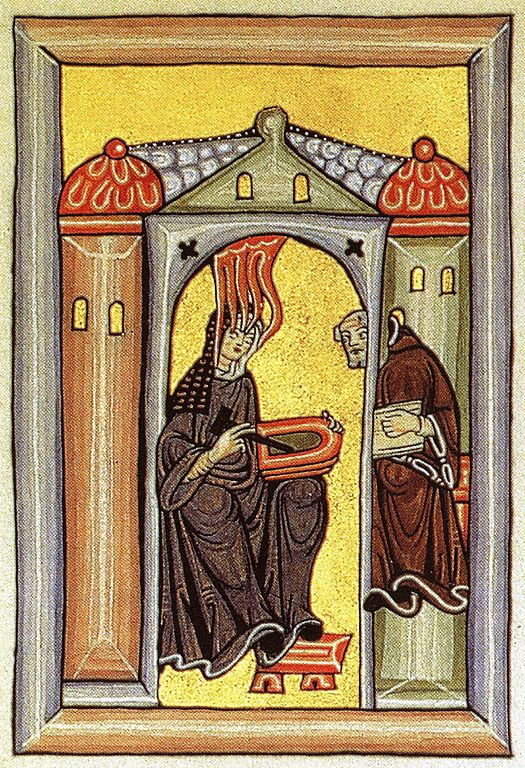

Hildegard von Bingen, or Hildegard of Bingen in English was a nun and abbess of the Benedictine Order. She has also been variously called Saint Hildegard or Sibyl of the Rhine. Hildegard lived in the 12th Century (1098-1179) and was from the Rhineland in the Holy Roman Empire.

She was a polymath who worked on and published material on philosophy, mysticism, natural science, theology, botany, medicine, and many other subjects. She was also an important composer, dramatist, poet, preacher, prophetess and seer. She left more songs after her than any other medieval composer, and she is one of the few composers to have written both the music and the lyrics.

Hildegard was a great idealist and one of the most important scholars of the Middle Ages. She was popular, and people from all walks of life knew about her and her works. What makes Hildegard unique is that she did all this remarkable work when women rarely had the opportunity.

Renaissance of the 12th Century

The 12th Century saw a religious, cultural and social revival in many parts of Europe, often called the 12th Century Renaissance. Then both monasteries and nunneries became great learning centres, and education and scholarship were strengthened throughout the continent.

Usually, highly learned clerics and monks led scholarly work at this time, so Hildegard was far from a typical 12th-century scholar. There is nothing ordinary about her. Hildegard always played down her learning, but we cannot deny the ideological similarities of her works with some of the major works of Western Christianity. Therefore, it is clear that she was well educated and managed to improve her education further in the monastery.

We can see she knew the books of the Bible, the rules of the Benedictine Order, general Bible commentaries, sacred texts, and the works of the church fathers Jerome, Augustine, and Gregorius. She is also knowledgeable about Bede and other authors. And there is furthermore evidence that she was familiar with Greek and even Arabic medical texts. Despite the originality of her works, it is clear that Hildegard was a child of her time and followed the accepted ideas of interpretation of scripture and the worldview of that time.

Youth

Hildegard was born around 1098 in Bermersheim on the river Nahe in the Rhine Valley. She was born into a noble family and was the tenth child. In her childhood, she struggled with various illnesses and had visions. Her parents gave her at a young age as an oblatus to the Benedictine monastery in Disibodenberg. An oblatus is a person who lives with a religious order but is not initiated into the order. When children were sent as oblatus, they were raised by the religious order to be ordained later as nuns or monks.

It was common then for the youngest children of noble families to be sent to a monastery to be fostered. It is also feasible to assume that Hildegard’s visions and illness were the cause for her being sent away. She was probably not judged healthy enough to marry and run a household which was hard work. Most likely, she was sent away from home at eight and tutored by a nun named Jutta.

Hildegard and Jutta formed the core of the growing community of women associated with the monk monastery in Disibodenberg. Jutta also saw visions and attracted many followers who visited her in the monastery. Hildegard says in her biography that Jutta taught her to read and write, but Jutta had little education and was, therefore, unable to teach her much more than that. They also read the Psalms together, meditated, worked in the garden, nursed the sick and did manual work.

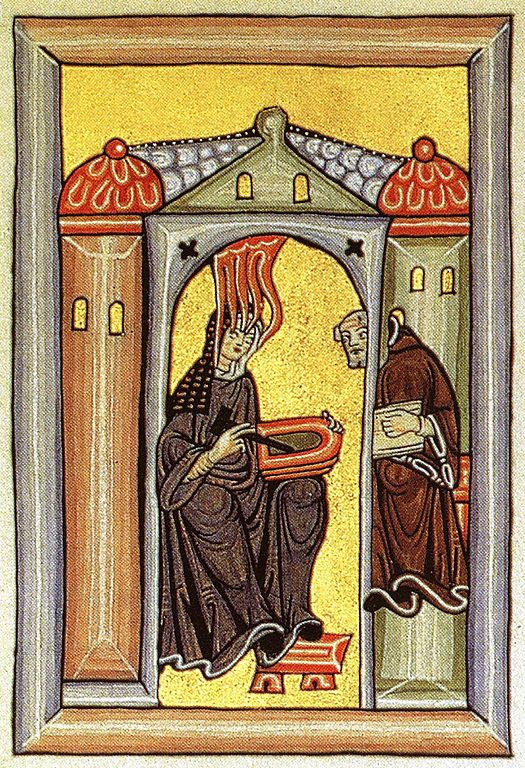

During this time, Hildegard also learned to play the ten-stringed psaltery. The psaltery is a harp-like instrument. The monk Volmar was a frequent visitor, and he likely taught her what Jutta lacked, including simple notation, which led Hildegard to compose music herself.

Upon Jutta’s death in 1136, Hildegard was named head of the nun community at Disibodenberg. Abbot Kuno of Disibodenberg wanted her to be prioress. Then she would be the official manager of the community of nuns in the monk monastery but under his control. However, Hildegard wanted independence from the monks, asked the abbot for permission to move to Rupertsberg and found a nunnery there. He refused her request, but after she went to all the superiors in the church and begged for permission, the abbot finally relented.

Hildegard and about twenty nuns moved to Rupertsberg monastery in 1150, where Volmar became provost and Hildegard’s secretary and confessor. In 1165, Hildegard founded another monastery in Eibingen.

The Seer

As early as three, Hildegard began to see visions but did not fully understand them until later. She realised that these were abilities she could not explain to others and kept them to herself. When Hildegard was forty-two years old in 1142, she had a vision in which God commanded her to write down what she saw and heard. She was very hesitant to write down the visions, it weighed heavily on her, and she became physically ill. She explained her hesitation as humility because she did not believe she could adequately put them into words. But the illness continued with a force, so she felt compelled to start, and when she began to write down her visions, the illness eased.

The first book she wrote about visions is called Scivias. The name is formed from the words Sci vias veritatis (or lucis), which means “know the way of truth (or light)”. I have also seen the book Sci vias Domini or “know the ways of the Lord” or “know the way”. The work was Hildegard’s first and one of the most significant turning points in her life. In the work, she describes each vision individually, but they are strange and mysterious and appear in the form of bright images of people, buildings or the universe. Hildegard then thoroughly explains their content to her readers, taking into account the worldview and theology of her time. A total of twenty-six scenes were included in the book, both in writing and in pictures. It took her almost ten years to finish the book (1142-1151).

In early 1148, the Pope sent envoys to Hildegard to evaluate her and her writings. The messengers found that her apparitions were real and returned to the papal court with the portion of Scivias that had been finished. At the Synod of Trier in 1147-1148, a section of Scivias was read aloud to Pope Eugene III and other bishops. The Pope then sent her a letter blessing her work. This papal letter was later interpreted as the approval of the Holy See for all of Hildegard’s theological works. She became widely known throughout Europe and was seen as a certified prophet, especially regarding doomsday, which is a large part of her work. In the last years of her life, Hildegard commissioned a richly illustrated manuscript of Scivias (called the Rupertsberg Codex). The original was lost when it was moved to Dresden for safekeeping in 1945, but it survives in a hand-drawn copy made in the 1920s.

The second theological book based on her visions was composed in 1158-1163. It was called Liber vitae meritorum or The Book on the Merits of Life. There she talks about morality by describing the grand conflict between virtues and vices. The work contains one of the first descriptions of purgatory as a place where people must stay to atone for their sins before getting to heaven. Hildegard’s descriptions of the punishments there are often disgusting. The book guides how to live a life of repentance and virtue.

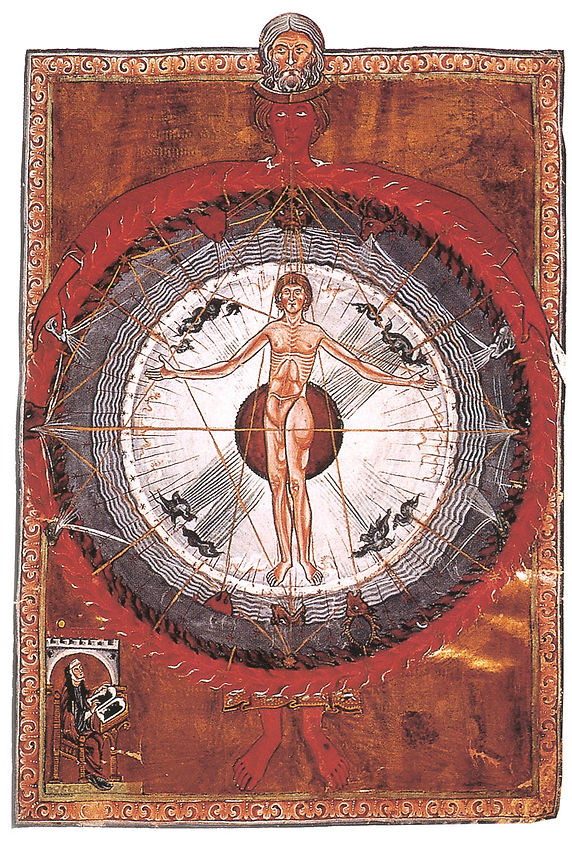

The third book based on Hildegard’s visions was called Liber Divinorum Operum, or The Book of God’s Works. It is also known as De operatione Dei or On the work of God. She wrote this book in 1163/4-1172 or 1174. This is Hildegard’s last book about her visions and the largest, and it is exceptionally beautifully illustrated. The book contains ten large and powerful visions, showing various ways of understanding the relationship between God and His creation and discussing in detail the position of man in nature.

The Composer

Hildegard is also known for her compositions and her musical. Apart from her musical “Ordo virtutum”, sixty-nine compositions have survived. Each piece has original lyrics. Four additional texts exist, but the music to them has been lost. This is one of a medieval poet’s largest surviving collections of music.

The musical Ordo virtutum (Rules of the Virtues) is one of her best-known works. The musical is a so-called “moral work” that deals with the soul’s struggle on the border between good and evil. The devil tempts the soul, but the chorus of virtues urges the soul to stand steadfast. This musical was the forerunner of the same kind of moral works that enjoyed great popularity almost two centuries later. The work is in Latin and is mainly made up of monophonic singing (a total of 82 songs). In the work, the music represents everything heavenly and virtuous, but satan speaks or screams. The musical is not connected to any ceremony or celebration within the church and is, therefore, the oldest known musical that is not connected to a church celebration.

Besides the musical, Hildegard wrote many hymns. They were later compiled into a single volume called “Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum” or Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations. The symphony’s songs are built around Hildegard’s original texts and include interludes, psalms, chants and responsories. Hildegard’s music is monophonic but still stands outside the tradition of monophonic monastic singing. With her, there is a powerful connection between the text and the song, but that was not common then. As with other medieval sheet music, there is a lack of markings on tempo and rhythm, so her work offers a wide range of interpretations.

The Scientist

In addition to writing books on visions, Hildegard also authored two books on natural science and medicine. In the monastery, she worked in medicine at the hospital and studied natural science while working in the monastery’s gardens. In addition, she had access to the monastery’s library. Despite being a nun and a religious leader, she reiterated that the secular world is good and humans are meant to use its resources. She became known for her healing abilities, mainly using tinctures (herbs or roots dissolved in alcohol), herbs or stones.

Hildegard’s first work on the subject, called Physica, consists of nine books describing the nature and healing power of plants, stones, animals and water. This publication is also the first to include a reference to the use of hops as a preservative in beer. Hildegard’s second work (Causae et Curae) deals in detail with the human body, health and various diseases. In both of these writings, Hildegard mixes accepted teachings with her observations. Her observations show us her sensitive understanding of nature.

Hildegard is believed to have used her books as teaching material for other nuns and assistants in the convent. Women healers in earlier ages rarely wrote down their methods. Hildegard’s books are, therefore, an important historical source. Hildegard’s philosophy of health has gained popularity in recent years with the resurgence of holistic medicine and herbalism.

Her Legacy

Hildegard’s writings were popular in the Middle Ages, and soon after the advent of printing, her works were printed on a large scale. In recent years and decades, interest in her work has grown again. Her writings have been republished, her music has been recorded, and cookbooks have been compiled based on instructions in her work.

She travelled a lot and gave lectures, sermons and exhortations, many of which have been preserved. This is fascinating since it was generally not accepted that women go out among the people to preach, teach and interpret the scriptures, even if it was a well-known abbess and prophet. Not only did she speak in monasteries, but she went on four preaching tours around Germany, speaking to both clergy and laity in congregations and public places. Most of her sermons focused on the clergy’s corruption, where she called for reform.

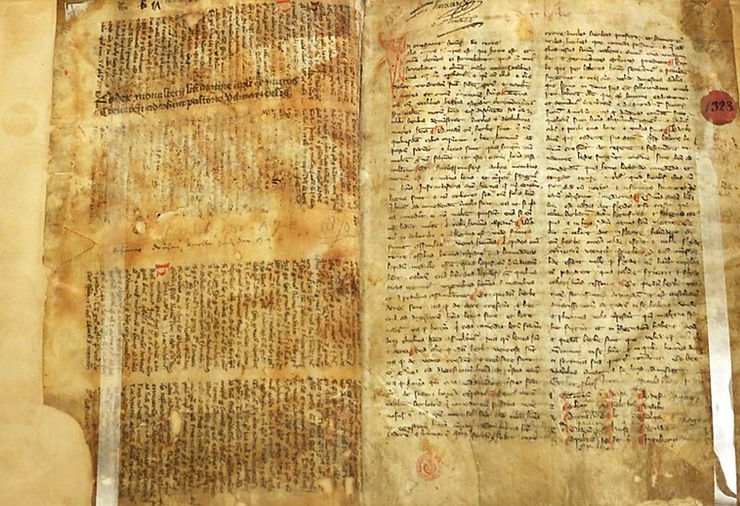

We have a unique insight into the life of the abbess, as nearly four hundred of her letters have been preserved in one of the largest collections of letters from the Middle Ages. The letters contain her correspondence with many of her most prominent contemporaries. She corresponded with the likes of German Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, King Henry II of England, Empress Bertha of Constantinople, Bernard of Clairvaux, Abbot Suger, and Popes Eugene III and Anastasius IV, among others.

However, she did not fawn over these famous people in her letters but instead criticised them freely if she thought their behaviour was inappropriate. She particularly criticised all corruption and how offices were bought and sold. She was always a fighter who went her way and left her mark on the masculine 12th Century.

When Hildegard was younger, she was often too weak to walk and sometimes lost her sight. As an adult, she sometimes lay paralysed in bed for days. Scientists now think it is most likely that she suffered from severe migraines. But despite persistent illness and infirmity, she managed to live to be eighty-one years old.

Leave a comment