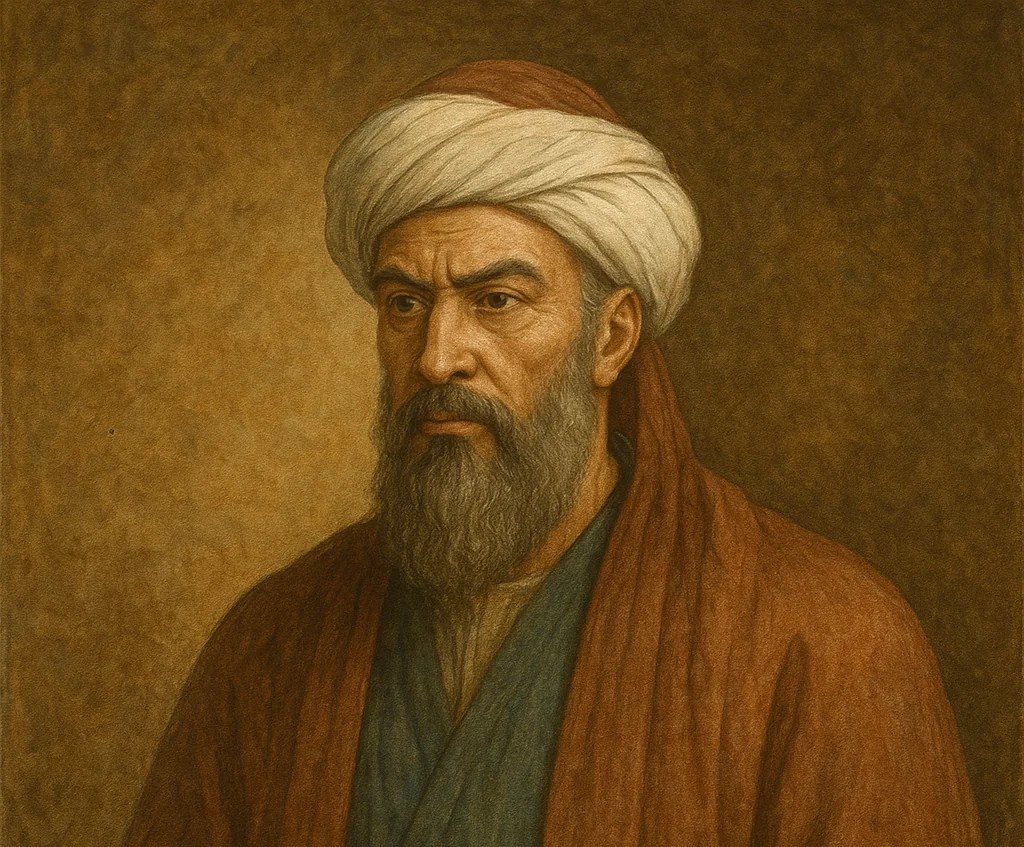

Hasan Sabbah was one of the greatest theologians and religious leaders of the Middle Ages and – if the stories are true – the founder of a secret order of assassins. A man is named Hasan bin Ali bin Muhammad bin Ja’far bin al-Husayn bin Muhammad bin al-Sabbah al-Himyari. We use here the abbreviation Hasan Sabbah, often also written Hassan-i Sabbāh.

Hasan Sabbah’s life revolved around scholarship, piety, prayer and austerity, which is nice but not very exciting. What makes him infamous is the assassin order he founded. The assassin’s order was still not the main thing in his life. The order was just a side project, so to speak, in his career as the leader of a religious state.

Hasan was the founder of the so-called Nizari Ismaili state. As the name suggests, the state is named after a man called Nizar. Hasan Sabbah supported the struggle of Nizar and his descendants to become the imam (leader) of the Ismailis in opposition to the imams of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt.

Hasan Sabbah was the founder of the military wing of the Nizari Ismailis. The members were called fidā’i in Arabic. In the West, they became known as the Order of Assassins. Other Muslims also called them Hashshashin because of their heavy consumption of hashish. The word Hashshashin later evolved into “assassin” in English, which is still the primary expression used for killers.

When Marco Polo heard of Hasan Sabbah during his travels, he was called the Elder of the Mountain, and this is how he was introduced to Europeans in the Middle Ages through Polo’s writings. As a missionary, Hasan converted the people of the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran to Nizari Ismailism in the late 11th century. In 1090, he captured a mountain fortress called Alamut and remained there until his death, ruling the Kingdom of Nizar.

Surrounded by enemies on all sides, Hasan regularly sent out a team of trained assassins to eliminate people considered dangerous to the state’s security or the existence of the religious community. Supporters of Hasan’s work choose to describe these shady operations as covert military operations against stronger opposition. Others call it terrorism. Either way, Hasan Sabbah is an interesting and contradictory personality. An ascetic who had an army of assassins working for him.

Childhood Years

We know little about Hasan Sabbah’s childhood. We know that he was born in the city of Qom in Persia around the year 1050. He was born into a Twelver Shia family- a Shia sect that recognises the Twelve Imams, descendants of Muhammad’s brother-in-law Ali. His father, Ali b. Muhammad b. Ja’far al-Sabbah al-Himyari was from Kufa in Iraq but moved to Qom, one of the first Arab settlements in Persia and the main stronghold of the Twelver Shiites.

Early in Hasan’s life, the family moved to Ray (sometimes spelt Rey, Rayy, Rayh), about 120 km from the modern-day Iranian capital, Tehran. Ray was a melting pot of various religious doctrines. The city was known as a centre of radical Islamic thought. Hasan became very interested in metaphysics and studied the tenets of the Twelver Shias. During the day, he studied at home and mastered palmistry, languages, philosophy, astronomy and mathematics (especially geometry).

But Ray was also a centre for Ismaili Shia missionaries. At the time, the Ismailis were a growing movement in Persia and other countries east of Egypt. Unlike Twelver Shias, Ismaili Shias only recognise the first six Imams and consider Ismail ibn Jafar the seventh and last. Of course, it’s more complicated than this, but we won’t discuss that here. The Ismailis supported the da’wa or “mission” run by the Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo. They submitted to the authority of the imam-caliph al-Mustanṣir in Cairo.

At a young age, Hasan contacted Amira Zarrab, an Ismaili, who introduced him to their teachings. Hasan was not impressed at first. But he is moved by Zarrab’s conviction, and after many passionate debates, he decides to delve deeper into the teachings and beliefs of Ismailism. Soon Hasan began to see the advantages of declaring his allegiance to the Ismaili imam. Hasan was 17 years old when he switched religions and swore allegiance to the Fatimid Caliph in Cairo.

Religious Division and Exile

Despite his young age, Hasan continued to study religion avidly after his conversion and earned respect within the Ismaili community. He impressed the region’s chief missionary, who made him a full-fledged missionary and advised him to go to the caliph in Cairo for further studies. However, we know Hasan did not leave Ray until a few years later when he fled after disputing with Nizam al-Mulk, who later became very powerful as a vizier in the Seljuk Empire.

It took Hasan about two years to reach Cairo, as he first travelled to Azerbaijan, Turkey, Armenia, Syria and Palestine, among others. Almost nothing is known about Hasan’s time in Egypt, and unclear how long he stayed there. Scholars, however, often mention three years in this context.

While in Cairo studying and preaching, he earned the enmity of the vizier Badr al-Jamali, who was the de facto ruler of Cairo. The office of the caliph himself was more symbolic than authoritative. The discord between them arose because Hasan sided with the son of the Ismaili and imam-caliph al-Mustanṣir. Hasan and al-Mustanṣir wanted the latter’s son, Nizar, to be the next imam. But Badr al-Jamali’s son and successor as vizier, al-Afdal, wanted to make Nizar’s younger and more manageable half-brother Qasim Ahmad the imam. When al-Mustanṣir died, al-Afdal succeeded in placing Qasim Ahmad on the throne, and Nizar fled to Alexandria.

Badr al-Jamali imprisoned Hasan. But when a prayer tower at the prison collapsed, he was released. The tower’s collapse was taken as a sign that his imprisonment was not acceptable to the divine powers. Hasan was deported instead.

Hasan’s life was now entirely devoted to the mission. There is hardly a town in Iran that he did not visit at this time. Hasan increasingly turned his attention to the mountainous area of the Daylam region in northern Iran. News of his travels reached Nizam al-Mulk, who sent soldiers to arrest him. Hasan managed to evade them and went further up into the mountains.

The Mountain Fortress of Alamut

Hasan’s search for a base for his mission ended in 1088 when he found the castle of Alamut (Eagle’s Nest). It is located in an area then called Rudbar but is today called Qazvin, Iran. At this time, Hasan had probably begun to form a militant ideology aimed at ridding Islam of what he called illegitimate heretical rulers and others who did not recognise Nizar, the true imam. If so, this remote and inaccessible fortress was an ideal base.

The fort at Alamut had been built in 865. It towered over a valley about fifty kilometres long and five kilometres wide. It took Hasan almost two years to conquer the fort, and he did it without bloodshed. First, he won the people in the villages in the valley over to his cause. Then he got the most consequential residents to convert in accordance with his teachings. In 1090, he was able to peacefully take over the fortress by having his converts blend into the ranks of its inhabitants.

Nizar himself had fled to Alexandria, where he was appointed imam. In 1095, Nizar was defeated by the vizier, taken to Cairo and executed. After Nizar was killed, the Nizari Ismailis were without an imam, and Hasan became the head of the Nizari mission. His title was hujjah, meaning deputy of the “hidden” imam. Hasan and his immediate successors were so-called hujjah, but the fourth hujjah, Hasan II, announced his resurrection as a “visible” imam. He was murdered shortly after, but his son also became an imam, and so on until today.

Under Hasan, Alamut became the centre of Nizari Ismailism. He knew the Koran by heart and had a comprehensive knowledge of the texts of most of the sects of Islam. And apart from philosophy, he was well versed in mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, medicine, architecture and the major sciences of the time. He spent the next 35 years teaching, translating, praying, fasting, and managing the mission.

Legend has it that Hasan devoted himself so faithfully to the scholarship that he never left his quarters, except twice when he went up on the roof. This story must be considered highly dubious in light of how capable an administrator he was and how successful he was in gathering troops for the military and organising the Ismaili rebellion in Persia and Syria.

Hasan indeed found solace in a life of ascetics and contentment. In his mind, a good life was a life lived in prayer and devotion. He was very strict in his doctrine with friends as well as enemies. Another legend says that Hasan once excommunicated someone for playing the flute because music was not part of religious life. He also had his sons executed, one for alleged murder and the other when he was suspected of drinking wine.

The Nizari Kingdom

It is a little difficult to reconcile this semi-monastic life and scholarship with Hasan’s worldly activities as an administrator. Hasan was the first of eight rulers of the so-called Nizari kingdom that ended with the Mongol conquest in 1256.

After taking Alamut, he gradually expanded the kingdom’s territory and acquired or built about twenty castles or forts scattered in various mountainous regions of Iran and Syria. Some of the forts were won by administrative skills, others by warfare.

Despite considerable distances and hostile territory between the forts, it was possible to hold the state together. The state even minted its own coins. The state was ruled after Islamic Sharia law, which is defined today as a “Theocratic Absolute Monarchy”. Hasan made the Nizar forts viable economic units by developing clever water supply and cultivation systems strategies. The forts became self-sufficient in food production, making it challenging to siege and starve the inhabitants out.

Despite many attempts by the Seljuk Empire, the Nizari state maintained its independence. The fort in Alamut was considered an impregnable fortress, and large armies could not break its defences down, although there were often few to defend it. It is quite an amazing achievement that in less than two years, Hasan Sabbah managed to establish an independent state in a few fortresses in the middle of the Seljuk sultanate.

The Assassins

Hasan Sabbah’s most famous legacy is undoubtedly the so-called fidā’i or militiamen of the Nizari state. As mentioned before, they were known as the Order of Assassins in the West. Other Muslims usually called them Hashshashin because they consumed hashish. From there, the word evolved into “assassin”, as we know it today.

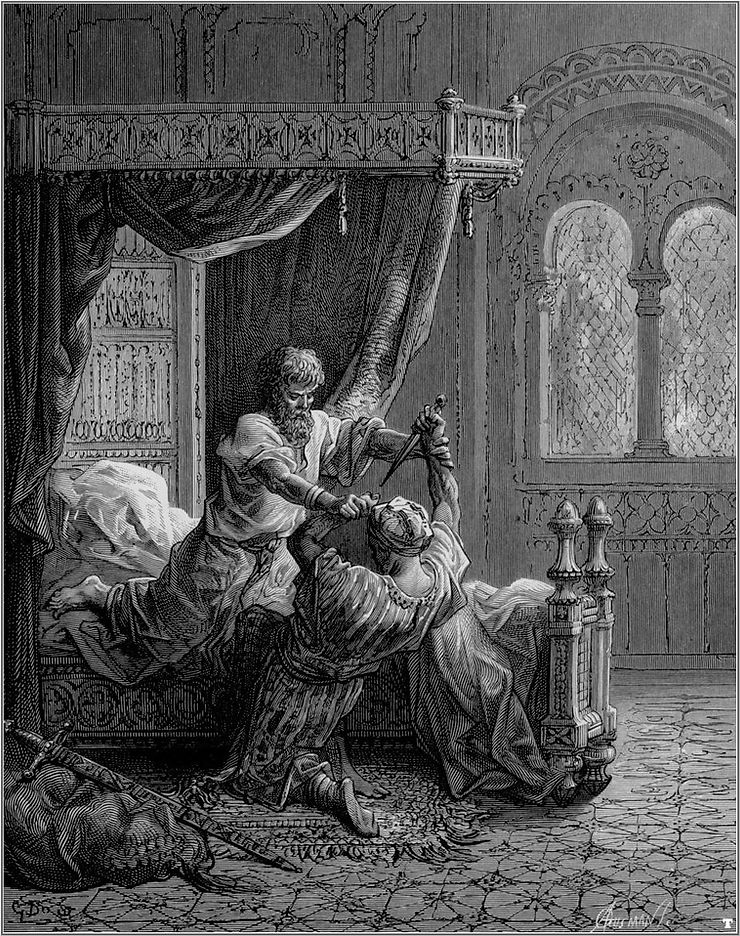

Hasan had few soldiers, and they were all busy defending the forts of the kingdom. They could not attack their enemies. The most effective method in the fight against the Seljuks and others was to use assassins who could sneak into the enemy’s ranks and kill key opponents. The Nizari Ismailis soon became known for this method, even though many states used such methods before and after them.

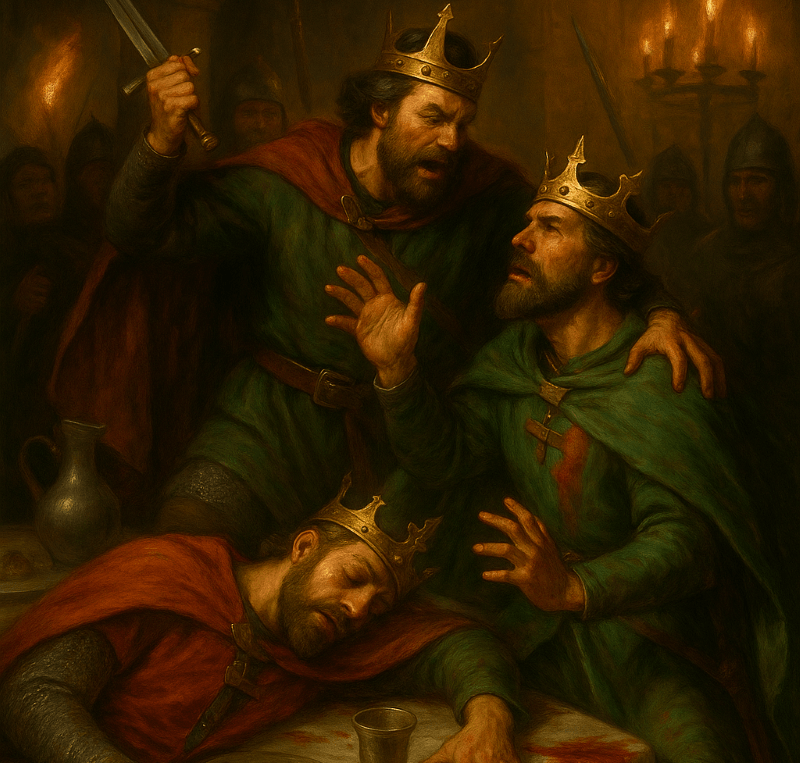

The first victim was Hasan’s arch-rival, the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk, who was assassinated on October 14, 1092, just two years after Hasan captured Alamut. Later, he also had al-Afdal killed along with a whole host of rulers, Christian and Muslim. We know the names of those killed and those who carried out the murders because they were listed in the roll of honour in Alamut. The last incident was in 1271, when an assassin wounded King Edward I of England with a poisoned knife while he was on a crusade.

The Order of Assassins became well-known because they were a prevalent topic among the Crusaders. The Crusaders were fond of the exaggerated stories of the assassins and how they carried out their killings in public places (they willingly committed murders in public places to gain publicity and to cause fear). Legends quickly began to form around these accounts. They told of their training, how they were promised “paradise” after completing their work, and how they were drugged with hashish to make them more daring and ruthless. Over time, the Nizari Ismailis came to be described in medieval European sources as a shadowy order of trained assassins committed to senseless killing and violence.

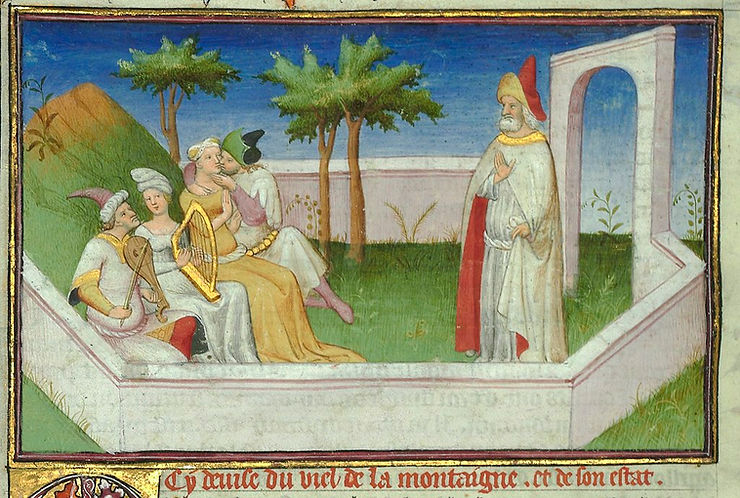

The legend about the training of the assassins is fascinating and well worth recollecting, even if we know nothing about its veracity. It describes how young men were brought to Alamut, where they were kept on bread and water in some basement hole and made to sit through daily religious lessons. There the students were slowly taught that Hasan and his successors held the keys to paradise.

One day a chosen recruit was drugged with hashish until he passed out. The next thing he knew, he woke up in a beautiful orchard (the gardens of Alamut were famous) where clear water flowed in streams, trees were full of fruit, and cute animals like lambs, peacocks, and deer were waddling around. In the garden, some beautiful women seduced the young man and indulged his every desire. The role of the temptress was to convince the novice that he was in paradise. After spending a few days in paradise, the novice was sedated again and placed in his inhospitable basement. The trainers told him he had spent a few days in paradise because of Hasan’s grace, and he could only get back there by dying for the cause. This method worked very well. Hasan had created suicide squads full of horny and overzealous young religious lunatics on hashish who were more than willing to die for the cause.

Heritage

Hasan died in 1124 after an illness. He chose Kia Buzurg-Umid of Lamasar as his heir and ordered him to take care of the kingdom until the true imam returned to take over. Hasan’s tomb was a popular place to visit among followers of Nizari Ismailism until it was razed to the ground by the Mongols in 1256.

It is difficult to discuss the legacy of Hasan Sabbah and his work as a religious leader and scholar without mentioning the assassins who did a valuable job for the Kingdom for a century and a half. Hasan’s achievement is building a kingdom from scratch that managed to survive for 166 years surrounded by enemies. And without his assassins, the achievement would have been impossible.

Hasan’s motivations for his rebellion against the Seljuks seem to have complex religious and political motives. As a Shia, it seems he could not tolerate the Sunni Seljuks’ hostility towards the Shia. Hasan’s rebellion was perhaps also part of Persian dissatisfaction with the rule of the foreign Seljuk Turks. An example of his national or ethnic feelings is that he took the unprecedented step of replacing Arabic with Persian in the Ismaili religious literature. This decision resulted in all Nizari Ismaili literature from Persia, Syria, Afghanistan and Central Asia being published in Persian for several centuries.

Many believe that the survival of Ismailism is due to Hasan. He and his successors supported the Ismaili study and established an infrastructure that stood the test of time even after the fall of the Nizari state. This school of Islam could have a role to play as a bridge between religions and promote tolerance and dialogue. Ismailism assumes that the same eternal truth is included within the three monotheistic religions; Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Ismailis practice an ecumenical approach to religion. Their Imams today, the so-called Aga Khans, have advocated cooperation with people of other faiths. Something we need more of.

Leave a comment