When it comes to engaging people in the Middle Ages, few are as interesting as Eleanor of Aquitaine (Aliénor d’Aquitaine). She was Queen of France when she was married to Louis VII and later Queen of England in her second marriage to Henry II. She was one of the wealthiest and most powerful European women during the High Middle Ages as the Duchess of Aquitaine and one of the leaders of the Second Crusade.

She had ten children in total. Three of her sons were crowned kings of England: Henry the Young King, Richard I the Lionheart and John Lackland. Two of her daughters also became queens: Queen Eleanor of Castile and Queen Johanna of Sicily. Eleanor was regent of England during Richard’s Third Crusade and often ruled through her husbands and sons. She is also known for her influence on medieval culture by promoting troubadours, chivalry and the ideas of pastoral love.

Growing Up and Childhood

Eleanor (Aliénor in French) was most likely born in 1122. She was the eldest of the three children of William X, Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers. Her mother was Aenor de Châtellerault, after whom Elinóra is named. Alia Aenor (Aliénor) simply means “the other Aenor” in Latin.

The Duchy of Aquitaine was the country’s largest and wealthiest province, almost a third of the size of modern France. Much larger than the territory the King of France ruled at the time. In the 12th century, “France” was a small territory around Paris, now called Île-de-France.

During Eleanor’s time, Aquitaine was a centre of culture, fashion and learning. Eleanor’s father placed a lot of emphasis on her getting a good education. She studied arithmetic, astronomy, Latin, literature, music and history. She received instruction in traditional women’s jobs of the time (housekeeping, embroidery, weaving, spinning). She learned conversational art, dance and various games such as chess. She played the harp and sang. On top of this, she learned horse riding, falconry and other hunting.

Contemporary sources praise Elinóra’s beauty. Despite all these praises of beauty, there is no accurate description of her appearance. All we know is that she was exceptionally well-rounded, lively, intelligent and strong-willed. Many thought enough was enough when women were supposed to be more reserved.

The purpose of her education was to prepare her for life as the wife of a powerful man. However, that was to change when she turned eight years old. Her four-year-old brother and their mother died in the spring of 1130. Suddenly, Eleanor became the heir. Her tutors started preparing her to be a manager instead of a manager’s wife.

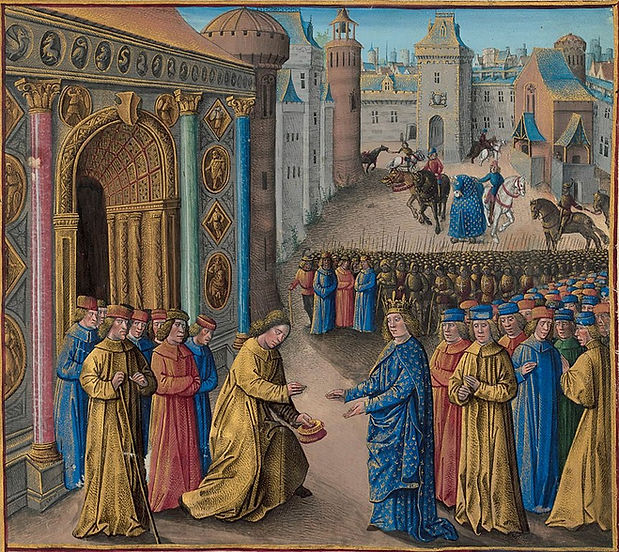

Eleanor’s father, William, died during a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela on Good Friday in 1137. At the age of fifteen, Eleanor had thus become Duchess of Aquitaine and Countess of Poitiers and, therefore, the most sought-after heiress in Europe. Kidnapping female heirs was a feasible option for gaining a title during this time. That’s why William requested that King Louis VI of France would be the girl’s guardian upon his death.

The king, known as Louis the Magnificent, was also seriously ill at the time, suffering from dysentery, and was unlikely to live long. When the first-born Philip died in a riding accident in 1131, Louis, his oldest surviving son, became heir to the throne. Upon the death of William of Aquitaine, King Louis saw an opportunity to bring Aquitaine under the control of the French crown and thereby significantly increase the power and influence of France. Within a few hours, the king had arranged for his son to marry Eleanor.

Queen of France

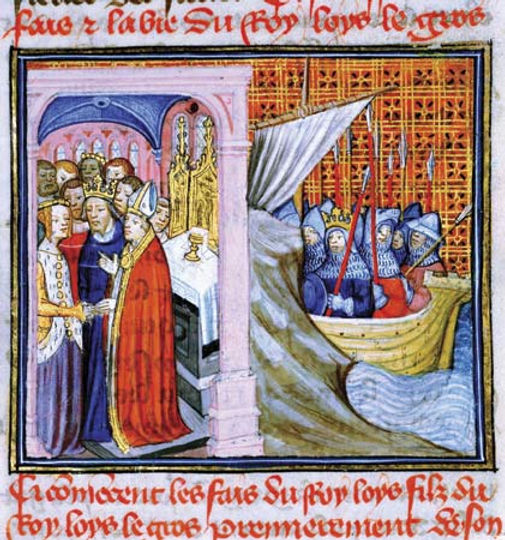

On July 25, 1137, Eleanor and Louis were married in the Saint-André cathedral in Bordeaux. Immediately after the wedding, the couple were crowned Duke and Duchess of Aquitaine. Both parties agreed that Aquitaine would remain independent of France until Eleanor’s eldest son became King of France and the Duke of Aquitaine. Therefore, Eleanor would not unite her holdings with France until the next generation.

The couple had only been married for a week when king Louis VI died. They had just gotten used to their positions in Aquitaine when they had to move to Paris and were crowned king and Queen on Christmas Day 1137. Eleanor was fifteen, and Louis was sixteen.

The plan was never for Louis to become king. He was to join the Church and was raised and educated at the Saint-Denis Abbey in Paris. His stay in the monastery had a significant influence on his personality. When he became king, he was ill-prepared and had an unsuitable temperament for administrative work. Eleanor was arguably much more capable of governing than her husband. She was much better prepared and had the appropriate education and character.

The king was madly in love with his wife. He gave her everything he could, even though her behaviour sometimes puzzled him. Having grown up at the famous court in Aquitaine, Eleanor found Paris unrefined and Louis boring and too pious. The court in Paris was stiff and sober, while Eleanor was lively. She was not popular with the court, who thought her frivolous and a bad influence on the king. Her influence on her husband and his politics is a matter of debate among scholars. Still, it is generally believed that she was more than an onlooker in those matters.

Together on a Crusade

In 1145, the couple decided to go on a crusade to the Holy Land at the instigation of Pope Eugenius III. The goal was to help the Christian states founded during the First Crusade. Eleanor took a group of courtiers and three hundred vassals from Aquitaine. She insisted on joining the crusade as the soldiers’ commander from her duchy. The legend that she and her maidens dressed as Amazons on their way to a battle has long been popular. However, we must consider this unlikely to be true.

The crusade was a complete failure. Louis was a weak and ineffective commander. He lacked all the ability to make informed and logical decisions in warfare. He was utterly worthless in maintaining discipline and spirit in the army. On the way to Antioch, his divisions separated due to indiscipline among Louis commanders. The rear division with Louis in command had retreated and fell into a trap where his men were slaughtered. Louis was lucky to be dressed as a pilgrim, not a king. He narrowly escaped unrecognised.

Eleanor’s youngest uncle, Raymond of Poitiers, was the prince and ruler of Antioch. Eleanor was delighted to see her uncle when they finally got there. His court reminded her of the court she grew up with in Aquitaine, they spoke the same dialect, and he was very kind to her. It must have felt great for her to finally meet relatives after a decade away from her family. They were together a lot, laughing, drinking and talking in a dialect Louis did not understand. It didn’t take long for rumours to spread that they were having an affair.

Raymond tried to get Louis to attack the Muslim camp at Aleppo. Aleppo was the key to recapturing Edessa, which was the main goal of the crusade ordered by the Pope. This suggestion was probably the best military plan in the situation, but Louis had no interest in fighting. Louis’s goal was to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Eleanor refused to continue with Louis and requested to stay with Raymond. She even started discussing the annulment of the marriage on the grounds of consanguinity. This talk did little to quell the rumours of Eleanor and Raymond’s affair. Louis decided to take Eleanor with him against her will and proceeded to Jerusalem.

Louis’s refusal humiliated Eleanora, and she stayed out of the limelight for the rest of the crusade – which did not bring any glory. The royal couple eventually decided to return home.

The Annulment

The trip home was eventful. They travelled on separate ships. First, they were attacked by Byzantine vessels that tried to capture them on the order of the Byzantine emperor. They escaped, but bad weather separated them at sea. No one heard anything from them for two months. Finally, Eleanor reached Palermo in Sicily, but Louis reached Calabria. Around this time, she learned of the death of her uncle Raymond, who had been beheaded in Aleppo.

This news changed the couple’s plans, and instead of travelling to France, they met Pope Eugenius III in Tusculum. The Pope refused Eleanor’s request for annulment and tried to reconcile the couple.

The Pope’s attempt at reconciliation resulted in another daughter, but Louis VII needed a male heir. He stated that a son was more important to the state than keeping Eleanor’s property. Therefore, Louis finally agreed to a divorce. On March 21, 1152, four archbishops, with the approval of Pope Eugenius, granted an annulment based on fourth-degree consanguinity. Their daughters were declared legitimate, and Louis got custody. Eleanor regained total control of her lands.

Queen of England

After the divorce, Eleanor was again a sought-after woman. On her way home to Poitiers, two counts tried to abduct her, forcing her to marry them and thus claiming her lands. As soon as she reached Poitiers, Eleanor sent messengers to Henry Plantagenet, Duke of Normandy and future King of England, asking him to marry her as quickly as possible. Eight weeks after the annulment of her first marriage, she married Henry.

Henry was even more related to Eleanor than Louis. Close family ties apparently didn’t matter when everyone was happy. And to make it even more interesting, the rumour was that Eleanor had previously had an affair with Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Henry’s father. There is, however, no evidence to corroborate this rumour. Eleanor’s private life was the most popular gossip of the time. Most of the time, people laughed at the expense of king Louis, especially after Eleanor had a boy with Henry a year after the annulment.

In 1154 Henry became King of England as Henry II. Eleanor became Queen of England and started to have children. In thirteen years, she bore Henry five sons and three daughters. They were William (died aged three), Henry the Young King, Richard the Lionheart, Geoffrey Duke of Brittany, John Lackland, Matilda, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria, Eleanor Queen of Castile and Joan Queen of Sicily.

While bearing all these children, she still took an active part in the kingdom’s management and an even more active role in managing her lands. She turned her court in Poitiers into a centre of culture, poetry, chivalry and courtly love.

Eleanor and Henry’s marriage was tumultuous. The relationship was certainly good enough to induce eight pregnancies, but in reality, Henry paid little attention to his wife. She had given him lands and many heirs; thus, her usefulness ended. He had numerous concubines for further entertainment and company. Eleanor chose not to make an issue of Henry’s illegitimate children. Geoffrey of York, for example, was Henry’s illegitimate son whom he recognised, and he grew up in Westminster under the Queen’s care.

By 1166, Henry’s love affair with Rosamund Clifford, often called The Fair Rosamund, had become well known, and the marriage seemed to be on the rocks. It appears that Eleanor agreed to a separation from Henry around Christmas 1167. At least she moved to Poitiers immediately after Christmas. Henry continued to rule all their lands outside Aquitaine, which was Eleanor’s responsibility.

In 1173 Henry the Young King, Geoffrey and Richard the Lionheart rebelled against their father. Eleanor took part in the rebellion with her sons. We don’t know how involved she was, but she at least provided them with some forces. The rebellion failed. Henry was gentle with his sons but put Eleanor under house arrest. She was in Henry’s custody until he died sixteen years later.

Rosamund Clifford, the love of Henry’s life, died in 1176. Usually, Henry tried to keep his love affairs secret, but his relationship with Rosamund was semi-public, and he did nothing to hide it. He may have done this to push Eleanor to seek an annulment. If that was the case, Eleanor disappointed him.

In 1182, there was another conflict within the family when the three oldest brothers warred. The conflict ended when Henry the Young King unexpectedly died of hemorrhagic fever while fighting against his father and brother Richard in the Limousin region. After the death of Henry the Young King, Eleanor gained a little more freedom. In the following years, Eleanor often travelled with her husband. She sometimes worked with him on the administration of the state, but she was still always under guard.

The Widow

When Eleanor got older and stopped having children, her role within the household changed. She became the uncontested matriarch of the family and exercised her authority over her sons. Eleanor became a tyrant and terror to her daughters-in-law and arranged her grandchildren’s marriages herself. She became, in a word, the formidable and terrifying mother-in-law.

Upon Henry’s death in July 1189, Richard became king. One of his first acts was to release Eleanor from her captivity. After she regained her freedom, Eleanor played a more significant role than ever. She took oaths of allegiance from lords on behalf of the king and prepared his coronation. Eleanor was regent while Richard was in the Holy Land and after his detention on his way home. She fundraised for Richard’s ransom and went in person to accompany him back to England. While Richard was absent, she managed to hold the monarchy together and defeated the intrigues of his brother John Lackland and King Philip Augustus of France.

It is safe to say that Eleanor was influential in the kingdom’s politics between her husband’s death in 1189 and her own in 1204. Her prominence is perhaps best seen in the long journeys she made in the kingdom’s interest, often in winter. Her most famous trip was to Spain. She, a 77-year-old woman, went on a perilous journey across the Pyrenees to convey her granddaughter back so she could marry King Louis VIII of France. With this, she hoped to establish peace between the English and the French. Despite her efforts, the peace did not materialise.

Eleanor survived Richard and well into the reign of her youngest son, John Lackland. She became his principal ally. Like Richard, John recognised his mother’s power and status. In the same year that Eleanor made her famous trip to Spain, she helped defend Anjou and Aquitaine from the attacks of Arthur of Brittany (her grandson), securing King John’s French possessions.

In 1202, when she was 80 years old, she again came to her son’s rescue by holding the castle of Mirebeau from Arthur of Brittany until John came and relieved the siege and took Arthur prisoner. King John’s only victories on the continent were thanks to his elderly mother.

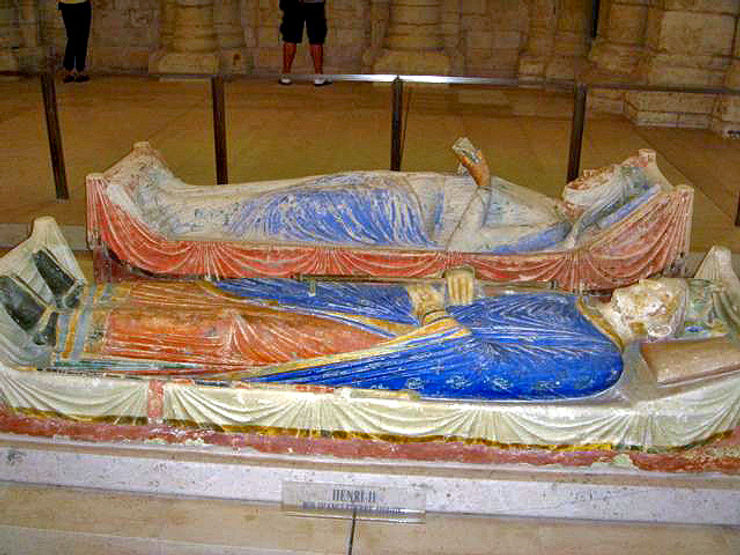

Eleanor died in 1204, then aged 82, in the family monastery of Fontevraud in the Anjou region, where she had retired. She outlived all her children except King John and Queen Eleanor of Castile. She was laid to rest next to Henry II and Richard.

Eleanor’s Influence

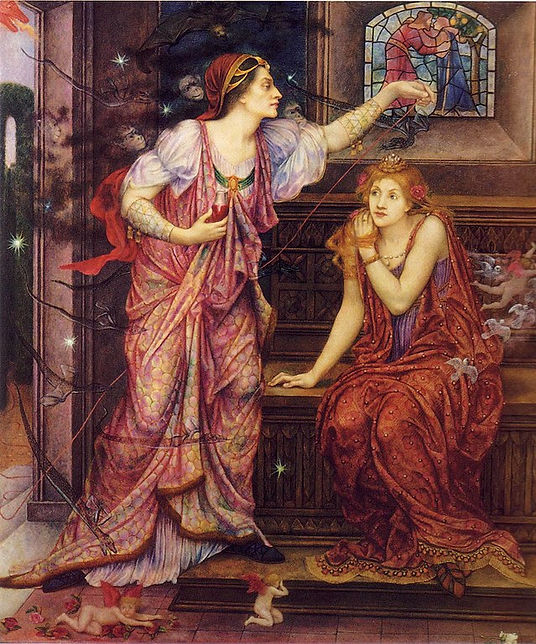

Eleanor has been considered a victim of bad husbands, an independent woman, an opponent of the conservative clergy, a cultural activist and a clever administrator. She has been described as a sensual, treacherous, independent, and easy-going woman. She was always the woman who drove men crazy, the Queen of the troubadours and their inspiration.

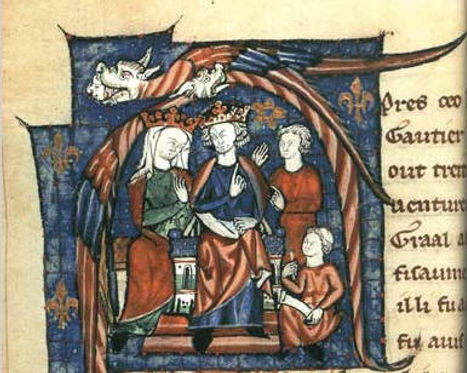

Scholars have long speculated about her cultural and literary influence and role in the cultural shaping during her lifetime. Some have claimed that she was a troubadour herself, although there are no sources to confirm this. Her closest son, Richard, was a great fan of this art form. And although she didn’t write any songs herself, it’s entirely possible that she was very interested in how to converse about love, adventures and court life.

She was a significant influencer and promoter of courtly love. The idea that she invented courtly love herself and sat in Poitiers with an assembly of courtiers to help her give romantic advice on sexual matters is most likely a myth.

The only source for this “court of love” in Poitiers is a book by Andreas Capellanus. He wrote about this a considerably long time after the events were supposed to occur. And we must bear in mind that Capellanus wrote for the court of the King of France, where Eleanor was not highly regarded. Others believe this court of love existed but was not taken very seriously. Its activities were more of a parlour game created to set rules for the local young courtiers.

Eleanor was one of the dominant influences of the 12th century, and literature as we know it grew alongside her and her time. However, one must not make too much of her role. But you can’t make too little of it either and ignore her completely.

Leave a comment