I was taught in high school that medieval people never bathed. They are said to have believed that dirt protected them from disease. Indeed, few quacks came forward with that theory when the Black Death raged. People were willing to resort to various measures against this deadly menace. But in general, hygiene in the Middle Ages was good and better than in the 16th century and beyond.

On Hygiene in the Middle Ages

People in the Middle Ages were not as clean as us, who have running hot water in our homes. However, people were still not filthy, covered in mud and smelly as you might think based on the image you see in movies and TV. People in the Middle Ages inherited many bathhouses and spas from the Romans and continued to use the facilities.

Notice that this article mainly concerns people in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. And bathing habits within this period depended on location, traditions, social status and eras. The Middle Ages were, after all, a thousand-year epoch. Different cultures called for different behaviours. For example, the Vikings were considered particularly clean and well-groomed, while others were perhaps not so to the same extent.

Let’s also remember that people in the Middle Ages were just ordinary people like us. The medieval man did not know about the relationship between hygiene and germs as we do today. But that still doesn’t mean they were content to be dirty and smelly. People then, as now, wanted to look good and keep themselves as clean as possible.

Like many other Middle Ages misconceptions, they date from the 19th century. Then the Middle Ages were seen as the “Dark Ages” of ignorance and barbarism; to some extent, this is still the idea held by many. An idea promoted in movies, television, and novels. For example, one 19th-century historian writing about life in the Middle Ages said that European people did not bathe for a thousand years.

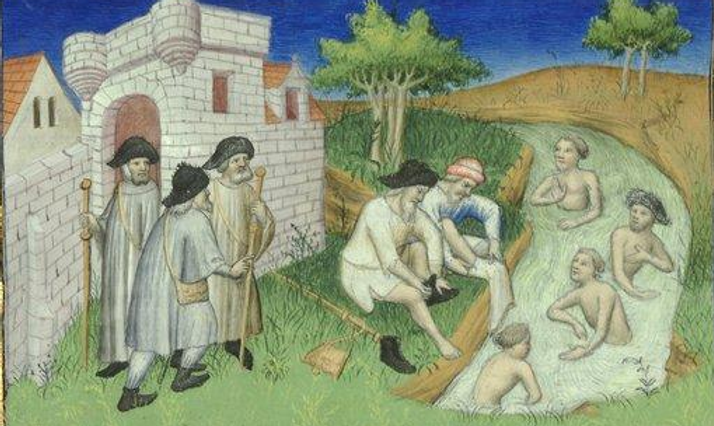

Indeed, there are stories of people who did not bathe. Saint Fintan of Clonenagh was said to wash once a year before Easter. We also see in sources that the Anglo-Saxons were shocked by Vikings who bathed once a week. But despite a few such stories, there are even more sources and works of art that show people cleaning themselves.

We see that people widely used combs and other sanitary products. Dental care was also important. People in the Middle Ages didn’t want to associate with or kiss people with bad breath and teeth any more than we do. Individuals cleaned their teeth with a cloth or used a coarse powder to scrub them. People also chewed herbs to get fresh breath. Since this was before the time of sugar, teeth decayed much more slowly than they do today.

Soap was widely used in the Middle Ages. It was often rough and not as good for the skin as today’s soap. But wealthier people had better access to soft soap made from olive oil. Soap makers even had guilds in big cities. Soaps and cleaning products became even more common after the Crusades when the Crusaders became familiar with the cleaning products of the East. Sources indicate that soap was used more often in the Middle Ages than in ancient times or the period following the Middle Ages.

Health publications from this time put a lot of emphasis on people cleaning off dirt and mud. A special effort was made to ensure everyone washed their hands and faces every morning. It was essential to wash hands before meals and altar processions.

For example, Magninius Mediolanesis wrote one such health treatise in the 14th century called Regimen sanitatis. He focuses on cleaning all body parts from the dirt that comes from the hustle and bustle of the day. He also mentions that if any impurities are still under the skin that did not go away with exercise and massage, they will go away with a bath. Magninius lists fifty-seven different methods for different cases. These include baths for older people, pregnancy, travel and more.

An entire section of the medical treatise Secreta Secretorum is devoted to baths. It points out that spring and winter are good times to bathe, but people should avoid washing in the summer as much as possible. The publication also warns that long baths lead to obesity and weakness. Medieval people also believed that baths could ease digestion and stop diarrhoea. But if the bath was too cold, it could lead to weakness of the heart, nausea and fainting.

Bathing the Rich

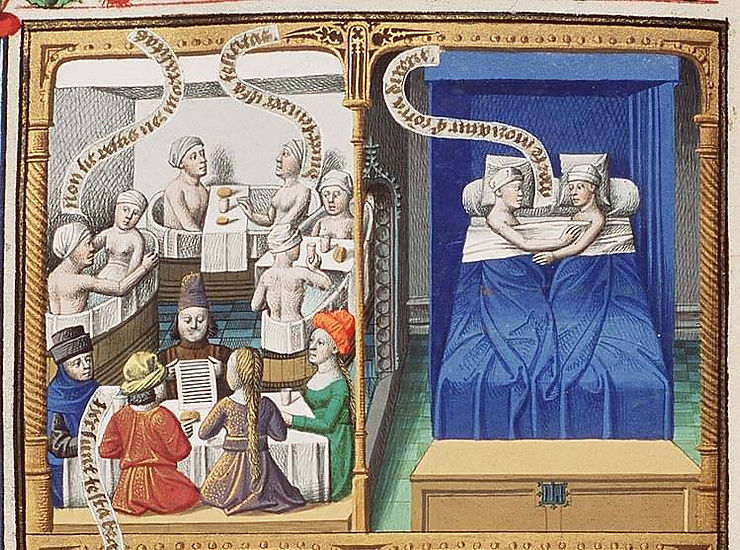

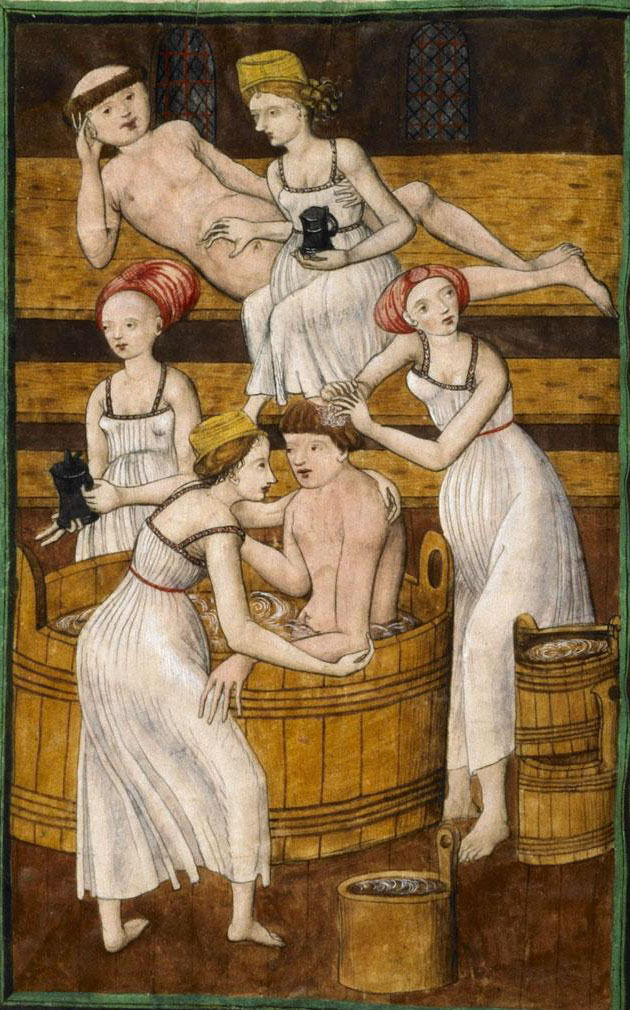

Wealthy people had private baths and bathed more often than the general public. Those with enough money had wooden bathtubs in their homes lined inside to avoid chips from the wood. Servants brought pitchers of hot water to fill the tub.

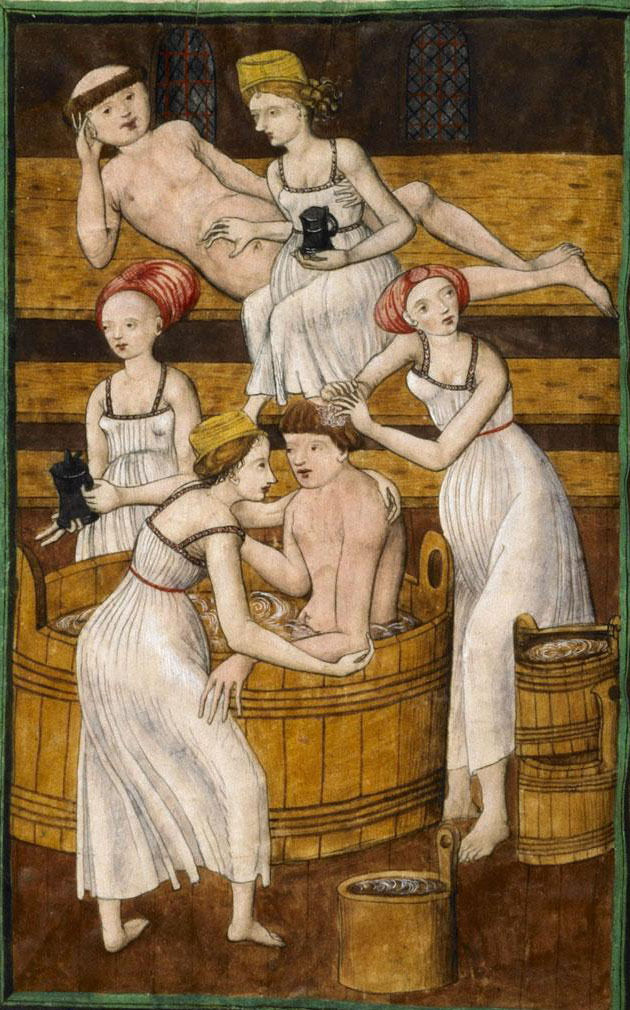

In a 15th-century servant’s manual, the servant was instructed to put a large sponge at the bottom of the tub and another five or six to sit on or lean against. They also had to put a sponge under the feet. The instructions said a sheet had to be strung over the bath so it would stay warm longer. It also said hanging sheets in the ceiling around the tub was good, each full of flowers and sweet green herbs. The servant was also to have a bowl full of hot and fresh herbs at hand and wash the person with a soft sponge. Next, the servant should rinse the person with warm rose water.

If the master or mistress was in pain, it was good to boil various herbs such as chamomile, fennel and other medicinal herbs and add them to the bath.

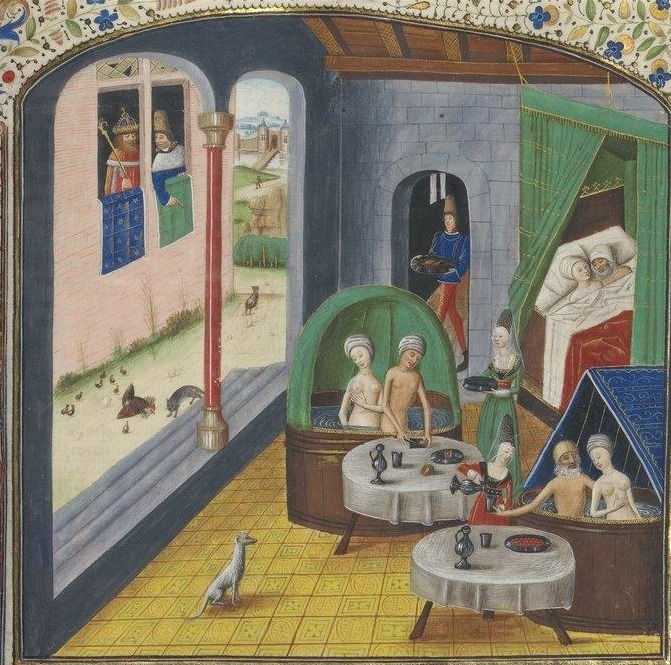

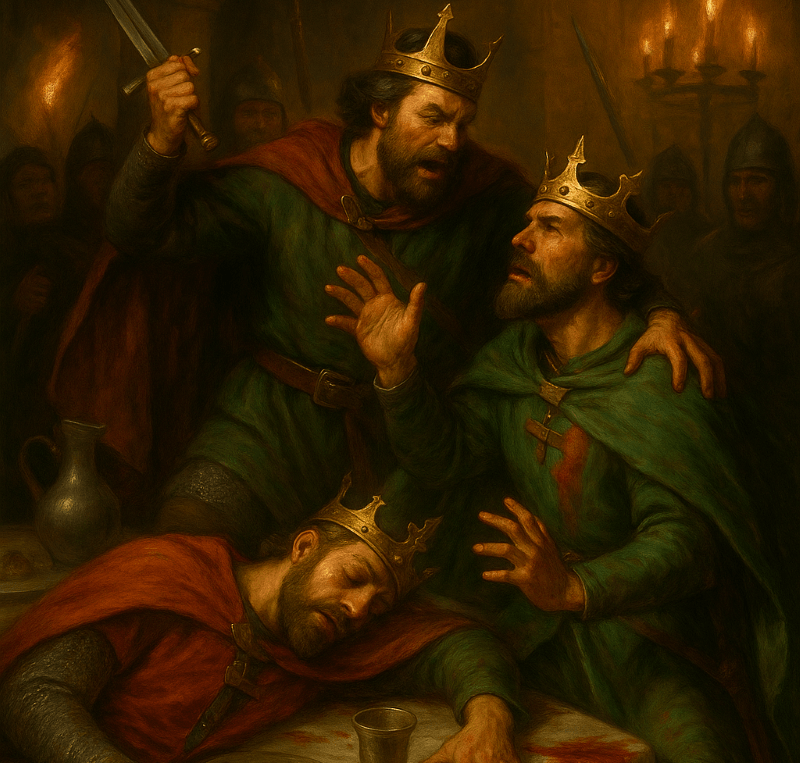

According to sources from the Middle Ages, kings often took such baths. There are records of kings who always travelled with a bathtub and employed a special servant to take care of the bathtub. We also know that Edward III had a faucet with hot and cold water connected to his bathtub in Westminster Palace in 1351.

Royalty throughout Europe entertained guests with baths and tried to impress each other with lavish bath parties. This custom goes back a long way because the historian Einhard says that Charlemagne loved to take a bath. He invited not only his sons but also his nobles and friends. Sometimes a group of assistants and bodyguards were also included, so the number of people present could reach a hundred or more.

The Church’s Attitude to Cleanliness

Christian clerics were full of condemnation towards pagan women who practised bathing naked in front of men. They did not like the Roman mixed-gender bathhouses either. But despite this, the medieval church encouraged its disciples to bathe in public baths. The church father Clement of Alexandria looked with approval on such baths. He declared that they promoted hygiene and good health.

The church even built public baths (where the sexes were separated) at monasteries and places of pilgrimage. The popes built baths within churches and monasteries in the early Middle Ages. For example, Pope Gregory the Great articulated to his followers the value of bathing.

Wealthy monasteries often had water piped into the cloisters and operated bathhouses for the brothers and sisters. The ordinances of the monastic orders often mention hygiene and bathing. In the rules, they were obliged to bathe at certain times. For example, the monks in Westminster Abbey had to wash four times a year – at Christmas, Easter, the end of June, and the end of September.

It is difficult to understand if these rules were a minimum standard for those who never wanted to bathe or if they meant that you could only wash during these times. We know that Westminster Abbey had a keeper of the baths who the monastery paid two loaves of bread daily and a subsistence allowance of one pound sterling each year. Therefore, everything seems to indicate that the monks used his services regularly.

Public Bathing

For everyone else, it was too costly to have a private bath. The public, therefore, used public baths, which were very common throughout Europe. In the 13th century, for example, there were more than thirty-two bathhouses in Paris. The town of Southwark, which stood south of the River Thames and is today one of the boroughs of London, had eighteen bathhouses. Smaller towns also had bathhouses. Then they were often combined with the local bakery, where the heat from the baking ovens was used to heat the water.

The baths were either Roman style, where many people bathed together in one pool, or a room with several tubs where few people could soak together in each. Medieval bathtubs were shaped like half a wooden barrel. Often the proprietor put flower petals in the water to give it a pleasant smell. The bathhouses charged entrance fees just as they do today.

Individuals often had bath parties where people met and ate together in the bath. According to 15th century records, we see that such bathing parties in public baths were as common and as natural as going out to dinner in a restaurant a few centuries later. German etchings from the 15th century often show bathhouses with long rows of naked couples eating in a tub, often several couples in each tub.

But the moral preachers were never far away. They criticized men and women for being naked in each other’s presence in the bathhouses. They claimed it provoked the danger of extramarital sex. Certain members of the Church were unhappy with this arrangement. Still, it appears the Church had little effect on the public baths. The Church even built such bathhouses herself, as mentioned before. In those bathhouses, however, there were stricter rules regarding associations between the genders.

In the Middle Ages, some towns were known as special bathing places or spas, and people travelled from far and wide to visit them. Bath in England is probably one of the most famous, but the Romans built a bathhouse there.

Rules were often strict in these places. For example, Pietro de Tussignano drew up twelve rules for the Italian health resort Burmi in 1336. Visitors who used the facilities were not allowed to have too much sex before arrival, but not too little either. How the overseers of the spa monitored this, only God knows. The guest had to attend on an empty stomach. However, it was permissible to have two spoonfuls of raisins and a little wine beforehand. You could only pour water over your head if your hair were clean-shaven; otherwise, your hair could hinder the effect of the water. The rules recommended the guest bathe for an hour a day for fifteen days. If everything went as planned, the bather would enjoy better health for the next six months.

The public baths were not only a place where people cleaned themselves and ate. Since everyone was naked, people often got energetic, and it was not uncommon for people to meet in the bathhouses to have sex. They were also convenient places for prostitution. In England, the bathhouses were often called “stews” because of their bad reputation. The authorities sometimes got involved, but most of the time, officers ignored their operation. The accepted attitude was that young men had to have a sexual outlet somewhere; it was better in a brothel than in society with “better girls”.

Not everyone had access to bathhouses—people in the countryside who couldn’t get to a bathhouse bathed in rivers and lakes. The very poorest in towns and cities who could not afford to pay to enter the bathhouses found other ways and tried to bathe wherever they could. Looking at medical records from the Middle Ages, we see that quite a few people drowned while bathing, so it was a deadly serious business. It was important enough to take the risk even though many could not swim.

The decline of Hygiene in the 16th Century

As early as the 16th century, the bathhouses began to disappear, and people’s washing habits moved into the home. That is, for those who washed at all. There were several reasons for this change. First, the Puritans of the 16th century had more robust and uncompromising values regarding freedom and sexuality. They were single-mindedly opposed to bathhouses and baths in general.

Second, all the diseases and epidemics that hit Europe in the second half of the Middle Ages were no less important in this development. It caused people to avoid the bathhouses. In addition to common plagues, syphilis appeared in Europe in the late 15th century. It caused a decrease in sexual promiscuity and a decrease in the number of brothels.

Third, medical manuals published after the Middle Ages and right up to the end of the 18th century recommended washing only those parts of the body that were visible to the public, for example, ears, hands, feet, face and neck.

In the Middle Ages, people mostly wore woollen clothing, but in the 16th century, people switched to linen clothing. Linen clothing is much easier to clean and maintain. In clean linen clothing, people looked clean even if they had not bathed. Therefore, the mindset gradually changed, and appearance and beautiful clothes became more important than cleanliness.

Doctors at this time believed that the smell (miasma) found in dirty linen caused disease. Therefore, it would be better to change your shirt every few days and avoid taking a bath, as this could allow “bad air” into the body through the pores. The emphasis on washing, therefore, shifted from washing the body to washing the clothes.

For example, there are stories about the native inhabitants of America who tried to convince the first Puritan settlers in the 17th century to bathe because they smelled so bad. King Louis XIV of France is said to have taken a bath three times in his life, and each time it was on the advice of a doctor. So not even kings seemed to bathe much during the period.

This misconception that medieval people did not bathe is undeniably reminiscent of people’s misconceptions about the Middle Ages and witchcraft. The witchcraft movement arose in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries with the Reformation. Then the Middle Ages had already ended. The same applies to bathing habits.

Leave a comment