By many, Gilles de Rais is considered the first serial killer in history. At least the first known one. The story of Gilles de Rais has long attracted people’s attention. He was a wealthy nobleman, a national hero in France after fighting alongside Joan of Arc, and then later, he was convicted of mass murder of children, torture, sex crimes and heresy.

Growing Up and Military Service

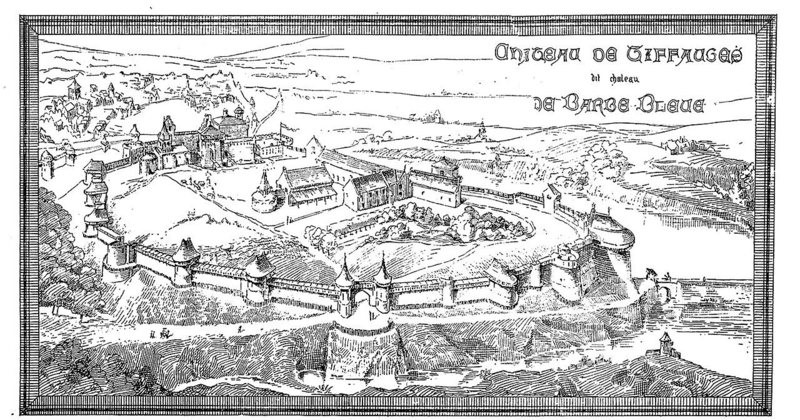

Gilles de Rais (born Gilles de Laval) was probably born in late 1405 at his family’s château in Champtocé-sur-Loire. He was the son of Guy II de Montmorency-Laval and Marie de Craon, both of high nobility and one of the most prestigious families in Brittany. As a child, he was considered very quick and intelligent. But also impulsive and short-tempered, traits that would later prove helpful on the battlefield. He spoke Latin fluently, was artistically inclined, and considered a skilled illustrator of manuscripts. On the one hand, his education was divided into traditional lessons and ethics of the time and, on the other hand, military science.

In 1415 both his parents died. We do not know how his mother passed, but his father died in a fishing accident. His maternal grandfather, Jean de Craon, fostered Rais and his younger brother. The grandfather tried his best to improve the boy’s fortunes further, and in 1417, when he was only twelve years old, he reached an agreement to betroth the boy to one of the wealthiest heiresses of Normandy, Jeanne Peynel, who was then only four years old. Her family later broke off that engagement. The grandfather even tried to betroth him to the Duke of Brittany’s niece, but it didn’t work out. In 1420 he married Catherine de Thouars, who was also wealthy and heir to La Vendée and Poitou. They had one child together in 1429.

The Hero

Gilles de Rais’s military career was superb. His first war was in 1420, the War of Succession for the Duchy of Brittany. Later he fought for the Duchess of Anjou against the English in 1427. From 1427 to 1435, Rais was a commander in the king’s army and was considered a brave and clever soldier. In 1429, he got the task of protecting Joan of Arc in battle. De Rais fought with Joan in many battles against the English and their allies, the Burgundians. He was with Joan when the French relieved the English siege of Orléans in a famous battle. He then accompanied her to Reims for the coronation of King Charles VII.

Gilles de Rais was richly rewarded with land and money and was made Marshal of France. He earned the privilege to include blue background with the royal fleur-de-lis on his coat of arms. He was by Joan’s side when she was captured by the Burgundians and handed over to the English, who burned her at the stake for heresy in 1431.

The Spendthrift

After Joan of Arc’s death, Rais withdrew more and more from the military. He had inherited rich lands from his father and maternal grandfather and married a wealthy woman and heir to a great fortune. Rais kept a more luxurious court around him than the king himself. He spent large sums of money decorating and refining his castle and had a large contingent of servants, soldiers, messengers and priests. He auspiciously supported music, literature and athletics.

Rais was highly religious and built a magnificent and ornate chapel called the Chapel of the Holy Innocents. He designed the clothes of the clergy himself and maintained a large children’s choir and voice coaches. He also staged a huge play, Le Mistère du Siège d’Orléans, which was mainly about the excellence of Joan of Arc.

The play was unusually long and extensive, with one hundred forty speaking roles and around five hundred supporting actors. Rais had six hundred costumes sewed for the first performance, but they were all thrown away after just one night, and new outfits were sewn for subsequent performances. All audience members were also offered unlimited drinks and food during the show. In other words, it was an astronomically expensive project.

All these adventures made Rais almost bankrupt, and he started selling properties. In the end, he managed to sell almost all his property but two of the family’s castles (there were thirty). Eventually, the family had enough and intervened. They got the king to issue a decree condemning Rais as a spendthrift and forbidding him to sell more property. The king prohibited his subjects from making agreements with Rais. As the Duchy of Brittany was independent and not under the king of France’s jurisdiction, Rais moved there but had to leave behind the properties he had not sold.

The Scientist

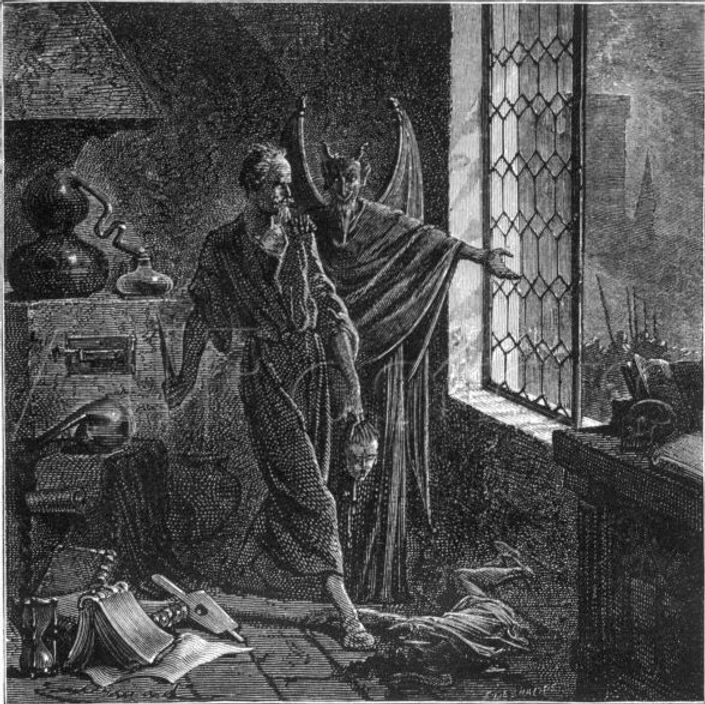

Since money was running out, there was only one thing to do: Alchemy. We should remark here that alchemy was not a crime. He was trying to turn worthless things into gold, which of course, failed. It would have been a blessing if he had managed to create gold; the story would have ended differently.

Instead, he sought help from all kinds of sorcerers and charlatans. He got in touch with a cleric from Florence named François Prelati. He claimed he was in contact with a demon named Barron and could help them. Rais didn’t want to sell his soul to the devil, but he was willing to do various things if the demon would help with his money problems.

Prelati claimed that the demon demanded sacrifices. His condition for help would be to get body parts from murdered children. People did not practice human sacrifices in the Middle Ages, so this is something that comes from Prelati. We do not know what he was up to, but this is where the child slayings begin.

In his later confession, Rais said that he began attacking children sometime in the spring of 1432 or 1433. The first killings occurred in Champtocé-sur-Loire, but no confirmed or documented account exists. Shortly after that, according to court documents, Rais moved to Machecoul, where he killed or ordered his associates to kill many children after sexually abusing them.

The first documented case concerns a 12-year-old boy with the surname Jeudon. He served as an apprentice to the furrier Guillaume Hilairet. Rais’ cousins, Gilles de Sillé and Roger de Briqueville, asked the furrier to borrow the boy to send a message to Machecoul. He never came back. The cousins told the furrier that he had probably been abducted in Tiffauges and put into servitude for some nobleman. Hilairet and his wife, the boy’s father, Jean Jeudon, and five others from Machecoul confirmed this story at the trial.

One of the key witnesses in the case against Rais was Étienne Corrillaut, nicknamed Poitou. He was Rais’ servant and accomplice in many of the crimes. He testified that his master undressed the children and hung them with ropes from the bottom of a hook to stop them from crying. Next, he masturbated over the child’s abdomen or thighs. If the victim was a boy, he touched his genitals and buttocks. Rais then took the child down, comforted it and assured it that he just wanted to play. Then he killed the child himself or had his cousin Gilles de Sillé, the butler Poitou or another servant named Henriet kill the child. The children were either decapitated, their throat cut, amputated or had their necks broken. Poitou also testified that Rais sometimes sexually abused the boys and girls before and after they died.

Poitou confessed that he and Henriet burned the bodies in the fireplace in Rais’ room. They then hurled the ashes into the sewer pit, castle canal or other hiding places. The last recorded murder was of the son of Éonnet de Villeblanche and his wife, Macée, in August 1440. Poitou paid 20 sous to have clothing made for the victim, who they then attacked, murdered and burned.

All the victims were children of poor farmers or beggars and were usually not missed. However, rumours persisted that children were disappearing. Gilles de Rais’s behaviour was an open secret in some quarters. For example, it emerged during the trial that witnesses saw his servants disposing of a dozen bodies in one of his castles in 1437. Still, the victims’ families refrained from taking action due to fear and low social status.

The Court Case

On 15 May 1440, Gilles de Rais arrived at the church of Saint-Étienne-de-Mer-Morte with armed guards and kidnapped a priest. This incident came about because of a dispute about lands. Bishop of Nantes arrested Rais and opened an investigation into his affairs. The investigation revealed allegations of infanticide and torture. On 29 July of the same year, the bishop published his findings and requested the assistance of the civil authorities in prosecuting Gilles de Rais.

Rais and his servants, Poitou and Henriet, were arrested on 15 September 1440 following an investigation by the civil authorities, who confirmed the bishop’s decision. The case was prosecuted in civil and ecclesiastical courts, and the defendants were charged with murder, heresy and sexual assault.

Here it is perhaps necessary to touch upon the judicial system in the Middle Ages. Christian Europeans were subject to two types of laws or judicial procedures. The second was the civil law which dealt with general crimes such as assaults, murders, thefts and the like. The other was church law (or canon law) which dealt with offences against the Church and religion. This system was often complicated because cases often overlapped. Ecclesiastical courts sentenced people to excommunication or other punishment but did not have the power to sentence people to death. If the situation called for it, the case was handed over to the civil authorities, who could sentence the person to death.

The extensive testimony of numerous witnesses convinced judges of both courts that the accused were guilty. In the court documents, you can see the testimony of several parents who described how their children went into Rais castle to beg for food but were never seen again.

There is no exact figure for the number of victims as all the bodies were burned and never found. Estimates say there were between one hundred and two hundred victims, but some have guessed at as many as six hundred. The ecclesiastical court counted a total of one hundred and forty victims, while the civil one counted two hundred. The victims were between the ages of 6 and 18, mostly boys.

However, in the indictment itself, authorities named only two victims. In the trial, ten victims were mentioned by name and an additional twenty-nine in connection with the testimony of family members who missed their children. This is not abnormal and does not affect the case’s reliability because even today, the number of victims is usually imprecise in serial killer cases. Serial killers are often convicted even though the charges are based on a small number of verifiable victims.

On 21 October, Gilles de Rais pleaded guilty to all charges, which meant it was never necessary to torture the story out of him. On 23 October, a civil court heard the confessions of Poitou and Henriet and sentenced them both to death. Gilles de Rais was sentenced to death on 25 October. He was convicted of heresy by the ecclesiastical court and sentenced to death for murder by the civil one. All the accused were to be hanged and then burned at the stake.

The execution took place the very next day. At eleven o’clock, Rais was hanged, and the pyre lit under him. However, his body was cut down before it started burning. Rais got this concession because of his aristocratic rank, i.e. to be buried instead of cremated. But that was the only concession he got. Usually, authorities did not hang nobles; this was a death for ordinary people. They beheaded nobles, which people at the time deemed a better death. Henriet and Poitou got no concession. They were hanged, and their bodies burned to ashes.

20th Century Theories of Innocence

Despite his confession, detailed accounts of eyewitnesses, and reports of his parents and accomplices, several people have put forward hypotheses about Rais’s innocence. These theories postulate that he was the victim of a conspiracy by the church or the authorities. However, most reputable historians believe that he did indeed commit the murders.

That Rais is entirely innocent is far-fetched, considering the number of testimonies. However, it may well be, and is even likely, that the other charges of torture, sexual abuse and heresy were added to increase the impact of the lawsuit, as was often done in the Middle Ages. However, that does not reduce the weight of the murder charge itself, according to scholars.

The structure of judical processes and the format of court cases were quite different from what we are used to today, and we modern people find many things strange about the process. For example, the man who prosecuted Rais, the Duke of Brittany, was the one who would be entitled to his property if he got the death sentence. Today we call this a conflict of interest and would not allow it. Modern theorists find this suspicious and hypothesise that the case was a conspiracy to steal Gilles de Rais’ assets. The counterargument is that Rais wasn’t a sufficiently juicy target after 1430. By then, he was running wild with his extravagance and financial indiscretion. If the reason for the accusations is financial gain, why wait to attack him until he had already sold all his assets and was almost bankrupt?

The lack of bodies also calls for scepticism. However, we do not know how thoroughly authorities searched for the remains of the victims. The records include testimonies of people who claim to have seen Rais servants disposing of bodies. Today, a judge would throw this out as hearsay. Being a noble in the Middle Ages, it was probably reasonably straightforward for Rais to dispose of or burn a body without incident. However, it is doubtful that he could have gotten rid of hundreds of human remains without being noticed. After all, we must consider it unlikely that the number of victims numbered in the hundreds, although it is almost certain that there were quite a number of victims.

Then we have the confessions. We always have problems with confessions from the Middle Ages because, in most cases, authorities obtained them through torture. At that time, torture was considered an acceptable and good way to get an admission of guilt, and such confessions were perfectly valid in court. The prosecutor did not torture Rais, but he threatened him with torture. How much it affected him is debatable. He was a tough and experienced soldier, considered brave and had experienced pain and horror on the battlefield. Whether he broke by being threatened with torture is uncertain. However, despite everything, he was very religious and, without doubt, feared excommunication or life in hell if he did not confess.

Scholars of medieval studies have criticised that there seems to be a bias or ill will towards the Catholic Church in the arguments of those who consider him innocent. There appears to be a tendency for the “if the Church condemned him, he must have been innocent” presumption. Today there is no such thing as heresy or alchemy. Cases in which one of the charges is heresy are, in our minds, fantastical from beginning to end, and the accused must be innocent. In the Middle Ages, prosecutors added heresy to increase the seriousness and importance of the matter. That does not mean that the entire court case was senseless. Magistrates usually judged murder cases based on testimony and evidence, and many of their sentences would still stand today.

It is impossible to write about Gilles de Rais without discussing the controversial trial from 1992. Several parties organised a “tribunal” to retry Rais’s case. This venture was part of some media event and took place without the official involvement of authorities and legal courts. A panel of lawyers, writers, former French ministers, members of parliament, a biologist and a doctor led by writer Gilbert Prouteau and presided over by judge Henri Juramy acquitted Gilles de Rais of all charges.

Scholars have strongly criticised this trial and consider it a complete mock court. The tribunal included no experts in the case of Gilles de Rais, nor were there any experts in legal procedure, law or medieval history. None of the participants knew anything about the judicial system at that time, their manner of speech, and what everything that took place in the first trial really meant.

Why was this informal trial initiated? Was this based on nationalism? We know that those who speak for Rais’s innocence are primarily French. Rais was a close friend of Joan of Arc, a symbol of French national pride. Is it discomfiting perhaps that a child mass murderer was part of the national saint’s story?

Conclusions

Rais’s case is altogether a sad matter. Sad for this national hero who fell from such heights and heartbreaking for the victims’ families. Rais was a man of true faith who descended into crime and depravity when he became desperate. But this happened over an extended period, and many factors caused it. There are so many things about Rais’s life that can corrupt the human soul: Unbridled power over the lives and limbs of his vassals, outrageous wealth, loss of parents at a young age, years of war (post-traumatic stress disorder?), a dear friend and colleague innocently burned at the stake for political reasons. Then he loses almost all his wealth in a short time. Lesser things have made people crazy.

His attempts to regain his wealth and former status. Did that lead him to practice human sacrifice? It is quite possible. It is difficult to place ourselves into the mind of a man who lived six hundred years ago. Someone might be crazy enough to kill children hoping for a quick profit. We have seen equally nonsensical things in our lifetime.

Leave a comment