The murder of Count Cenci is one of the most famous murders of the 16th century. The murder itself, however, is not the reason for its fame. The count’s daughter, Beatrice Cenci, has become the centre of the case over time. She has mesmerised those who have written about it. Beatrice has been described as a goddess of beauty, a fallen angel, and a pure and innocent 16-year-old virgin. She has likewise been portrayed as a hero who fought against the tyranny of the aristocracy. This article covers this exciting story, the case itself, and why Beatrice became legendary.

Romantic Revival

The Cenci case attracted some attention when it came up at the turn of the 17th century, but then it more or less fell into oblivion. It wasn’t until the Romantic poets took it up much later and retold the story in countless poems, short stories, novels, plays, and operas that the case became world famous. And that complicates the matter. You must dig past the Romantic poets’ epic descriptions to get to the story itself.

The romantic poets of the 19th century presented to their audience a shocking story of a teenage girl who killed her abusive father to protect her virtue and virginity from his advances. A girl who fought bravely against abuse and torture and faced her creator without remorse on the execution platform. She was promoted by the mob in Rome, which saw her as a hero and symbol of the fight against the corruption of the aristocracy.

We can find the roots of the Romantic revival of this case in the long and colourful account of the historian Ludovico Antonio Muratori in his 12-volume work Annali d’Italia published in 1740. In his work, the case returned to the public’s attention. Percy Bysshe Shelley became familiar with the story through Muratori’s writings, leading him to publish the play, The Cenci, in 1819, which drew even more attention to the case.

Shelly’s play is a sanitised version of Muratori’s narrative. The murder is beautified, and Beatrice becomes a sympathetic victim who has to choose between enduring incest or committing patricide. This description of Beatrice’s situation fitted in very well with the Romantic idea of the heart-wrenching protagonist.

Stendhal (1839), Niccolini (1844), Guerrazzi (1853) and Artaud, among others, also wrote works on the subject, and shorter essays were published by authors such as Alexandre Dumas the Elder and Swinburne. Even Alfred Nobel contributed. Stefan Zweig wrote a short story in the early 20th century, and a radio play and musical appeared after the turn of the 21st century. The story has been filmed many times. Then there are the sculptures and paintings made of Beatrice Cenci.

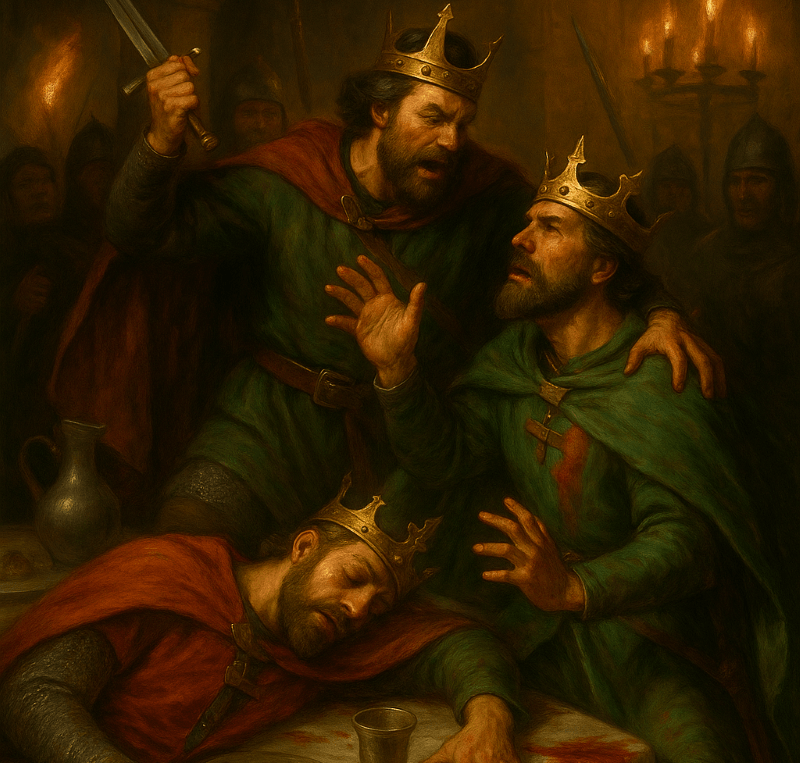

The Painting that Changed Everything

What most sparked the interest of the Romantic poets in Beatrice was a painting by Guido Reni (1575-1642). The painting (see at the top of the article) shows a beautiful young woman with brown hair and big shining eyes. Legend has it that the picture was painted in the prison where Beatrice stayed in late 1598 or 1599. However, it is doubtful that Reni had access to Beatrice in prison. Another story says that he saw her in the street as she was led to the execution.

We know that Shelly saw the painting in 1818 and fell head over heels over the girl’s beauty. Stendhal also wrote about the beauty of the imagery, and Charles Dickens found the painting unforgettable. Nathaniel Hawthorne commented that you could see a “sinless angel” in the painting. The image clearly had a significant impact on the hearts of middle-aged men. The feeling of protection toward this vulnerable girl must have flared up. And this undoubtedly had a great influence on how they saw the protagonist.

We now know that the painting is most definitely not of Beatrice. The painter Guido Reni did not paint in Rome until nine years after Beatrice’s death. The composition, clothing, and pose, suggest that the image is more likely of one of the prophetesses of antiquity, a popular subject at the time. Reni made several such paintings. It is also suspicious that Beatrice was not associated with this painting until two hundred years after the work was painted. Just when her fame was on the rise.

The Family

The Cenci family was an ancient Roman noble family and could trace its lineage back to the gens Cincia in the ancient Roman Empire. Beatrice was the daughter of Francesco Cenci, a wealthy and influential count, and Ersilia Santacroce. Beatrice’s mother died when she was seven.

The family owned the castle of La Rocca in the small town of Petrella Salto, located in the Abruzzi mountains, northeast of Rome. However, the household lived mainly in the family mansion in Rome, Palazzo Cenci. There, Beatrice lived with the count’s second wife, Lucrezia Petroni, and brothers Bernardo and Giocomo. Beatrice had other siblings, but they are not relevant to our story. The family were not exemplary citizens; the young sons misbehaved, and two died after duelling.

The main problem of the family was the pater familias, Francesco. He was, in a word, an immoral brute, and everyone in Rome knew it. He primarily used his wealth to bail himself out of prison. For example, he took a concubine while married to Lucrezia, beat the concubine and forced her to perform sexual acts against her will, leading to a conviction for “unnatural impulses”. He also pleaded guilty to abusing young boys in three separate court cases. While others were executed for lesser reasons, he always escaped with a fine and a few months in prison.

His sons sent a petition to Pope Clement VIII asking that he would be put to death as required by law – to save the family’s honour. But Francesco always escaped by padding the papal coffers with donations.

He did not treat his own family better. Beat his wives, daughters and sons mercilessly. And since he spent everything on fines and bribes, he had no means to feed or clothe them. Beatrice’s older sister finally gave up on living with the family and pleaded with the pope to send her to a convent or marry her away without the father’s permission. The pope married her to a Roman nobleman and forced Francesco to pay a dowry against his will.

The Murder

In 1595 Francesco sent his wife Lucrezia, along with Beatrice, to the family castle of La Petrella as captives. It is believed that he wanted to get Beatrice out of Rome, either because she sent complaints to the Pope and other authorities about his behaviour or because he wanted to avoid paying a dowry to potential suitors, as happened with the older daughter.

Three years later, in the early morning of 9 September 1598, when Francisco was visiting the castle, the neighbours in the village heard screams in the morning silence. It was Lucrezia who had screamed.

The villagers found Francesco’s body lying in a rubbish heap directly below the castle. He appeared to have fallen through a wooden balcony surrounding the castle’s top floor. Parts of the balcony were broken, but the hole that had been made in the floor seemed to be too small for the count’s tall body. It also seemed strange that the body was already cold, indicating some time since the count had died.

More questions arose when they washed the body. Three wounds were found on the side of the head; two smaller wounds on the right temple, but the deepest and ugliest wound was near the right eye. The count also had a bruise above his right wrist.

The local police investigation was thorough, and no one questioned its findings. The count had been brutally murdered. First, his wine was poisoned by his wife. Then two men entered his room. The count woke up despite the intoxication, but the men held him down (the bruise on his left arm); one put an iron spike to his head while the other drove it in with a hammer. The two smaller wounds were most likely failed blows, but the coup de grâce caused the third and most significant injury near the right eye. The intruders then dressed the body and threw it onto the rubbish heap below the castle. The killers tried to make a hole in the balcony floor to make it look like an accident. But at the same time, they left a lot of evidence, such as blood-soaked bedding.

The two men were Olimpio Calvetti, the caretaker of the castle and Beatrice’s secret lover, and Marzio da Fiorani called Catalano. However, they were just hitmen. The real organisers were Lucrezia, Beatrice, and the brother Giacomo. During questioning, it emerged that Beatrice was the most determined of the conspirators, egging on and encouraging the assassins when they wavered at the last minute. But she refused to confess, even under torture. Other family members were brutally tortured and ended up confessing.

Both assassins died before a verdict was handed down. Olimpio Calvetti was killed on the run, and Marzio Catalano was tortured to death. At dawn on 11 September 1599, they brought the family to the square in front of Castel Sant’Angelo, where the gallows had been erected.

Giacomo was driven in a carriage. While being driven to the execution, he was disfigured with boiling tongs. When he got there, he was beaten to death with a wooden hammer, and the body was dismembered. The women walked to the place of execution, unbound and in mourning clothes. They were then decapitated. Twelve-year-old Bernardo Cenci was deemed too young to take an active part in the plot; he escaped with his life but was forced to watch his family’s execution and was sentenced to life as an enslaved person. A year later, this sentence was commuted, and he was released.

Later Discoveries

In 1879, a considerable time after the folklore about Beatrice took off, Dr Antonio Bertoletti published his research into the family documents found in their archives in Rome. He found many interesting facts. For example, he discovered that Beatrice was born on 6 February 1577 and was almost 23 years old when she was executed. She was not 16 or 17, like in the imaginations of the romantic poets.

The documents also contained Beatrice’s will. Most notably, she instructs her friend, the widow Catarina de Santis, to deliver a substantial sum of money to “a certain poor boy” in accordance with a verbal agreement between them.

This in itself does not prove anything. But why would Beatrice bequeath her money to a poor boy unless there was some connection between them? It is, therefore, very likely that this boy was her son. For this reason, it is also safe to assume that the boy’s father was her lover Olimpio Calvetti. This begs the question of whether Beatrice’s imprisonment in the family’s castle was not to hide the girl’s pregnancy.

These documents change the image we get from the Romantic poets. The innocent girl in Guide Reni’s photo turns out to be an almost 23-year-old woman. A woman who was not a chaste virgin but a mother of an illegitimate child and the mistress of her father’s murderer. A woman who did not break down under intense torture and was, in truth, a tough and formidable person. She was not an innocent child but an adult perpetrator. However, these particulars do nothing to lessen her terrible situation or make light of her father’s brutal abuse.

Did her father indeed sexually abuse Beatrice, as the Romantic poets claimed? During all interrogations, she stated that she had no reason to kill her father. Nothing was revealed during the interrogations and torture of her and others about sexual violations. No one mentioned incest in the investigation or the court case until Beatrice’s lawyer made the statement in his closing arguments. But what does that prove? He was doing his job presenting every possible argument to mitigate the sentence.

In the last interrogation on 19 August 1599, Beatrice articulated that her stepmother Lucrezia urged her to kill her father, or he would end up abusing her and depriving her of her honour. This statement implies that sexual violence was a possibility rather than already occurring.

Many things were extraordinary in the household. The count had a very itchy skin disease, and he had to scratch and scrape his skin. According to the testimony of their maids, it was Beatrice’s job to scratch her father, even on his testicles. Beatrice also had to hold the chamber pot before her father as he relieved himself. This shows he was not a pleasant or considerable man but does not prove he was a rapist or incestuous.

It is not possible to prove or disprove anything in this matter. Many in the family had a reason, or reasons, to kill the count. This murder was maybe committed due to one of those reasons. Or perhaps it was something else entirely. Or all of them together.

But whatever it is that happened, Beatrice lives on in the memory of the people of Rome. It is said that every year on the eve of her death, she re-walks over the Sant’Angelo Bridge, holding her severed head.

For a long time after her execution, Beatrice was a symbol of resistance against the arrogance of the upper class. Many citizens thought the sentences were far too harsh and that no consideration was taken to the situation within the family. But at this time, the head of the family was a dictator, and his word was law. Pope Clement VIII was adamant that the sentence would be carried out so this case would not create a precedent for patricide. However, a more popular – and more plausible – Roman public theory about his stance was that with the death sentence, the family property was confiscated by the court and given to a close relative of the pope.

Leave a comment